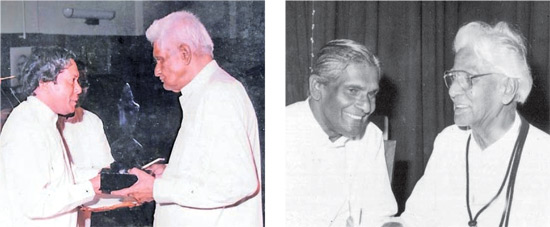

The late Pundit Wimal Abhayasundara is one of the foremost poets from the Colombo School of Poetry. He is not only a poet, but also a lyricist, radio script writer, broadcaster and author of dozens of books, some of which won State literary awards.

The master of several languages, Abhayasundara was born on September 17, 1921, and died on June 12, 2008. His centenary birth anniversary was scheduled to be commemorated last year, but due to the Covid-19 pandemic the commemoration ceremony was postponed to this year. Now it is all set to mark the event with republishing of his four books along with a new felicitation volume. In this backdrop, The Sunday Observer spoke to Professor Praneeth Abhayasundara, the eldest son of Pundit Wimal Abhayasundara, to discuss his memory about his father. Prof. Praneeth is a lyricist on his own right, an author of many books and a Senior Lecturer, Department of Sociology and Anthropology, Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences, University of Sri Jayewardenepura.

The master of several languages, Abhayasundara was born on September 17, 1921, and died on June 12, 2008. His centenary birth anniversary was scheduled to be commemorated last year, but due to the Covid-19 pandemic the commemoration ceremony was postponed to this year. Now it is all set to mark the event with republishing of his four books along with a new felicitation volume. In this backdrop, The Sunday Observer spoke to Professor Praneeth Abhayasundara, the eldest son of Pundit Wimal Abhayasundara, to discuss his memory about his father. Prof. Praneeth is a lyricist on his own right, an author of many books and a Senior Lecturer, Department of Sociology and Anthropology, Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences, University of Sri Jayewardenepura.

Excerpts from the interview:

Q: Both you and your father were involved in writing. How do you see your father at home?

A: Although my father was a prominent name for outside, he was a silent character in the family. He only spoke with us if he had something to ask. I never saw him in a conversation with someone who was not his guest. He had a study room in the house and he was always in it reading or writing. As my father sold his own house, those days we had to live in various rented houses.

I can recall all these houses comprised of a study room with a table and cupboards which he filled with books.

I have a vivid memory on how my mother treated his friends. Though he was a silent character in the house, he was talkative when his friends visited him. After they started their conversations, my mother made tea for them, sometimes supplied with biscuits.

Q: Who are the friends who visited your home?

A: So many friends visited. Some of them were Wimalendra Waturegama, P. Malalgoda, U.A.S. Perera (Siri Ayya), Karunarathne Abeysekara, Wijerathne Warakagoda, P. Dunstan De Silva, Amaradeva, Bingiriye Senarath Wijaya Kumara, Lal Hegoda, Nanda Hegoda, Sesiri Wijesekara, Galvehera Gunasekara, Upananda Batugedara, Talangama Premadasa, Bambarakotuwe Sunanda Senevirathne, Siril A. Seelawimala and Wimalasiri Perera, all of them were poets from the Colombo school of poetry.

A: So many friends visited. Some of them were Wimalendra Waturegama, P. Malalgoda, U.A.S. Perera (Siri Ayya), Karunarathne Abeysekara, Wijerathne Warakagoda, P. Dunstan De Silva, Amaradeva, Bingiriye Senarath Wijaya Kumara, Lal Hegoda, Nanda Hegoda, Sesiri Wijesekara, Galvehera Gunasekara, Upananda Batugedara, Talangama Premadasa, Bambarakotuwe Sunanda Senevirathne, Siril A. Seelawimala and Wimalasiri Perera, all of them were poets from the Colombo school of poetry.

Some bhikkhus also came to meet him. Especailly, bhikkhus from the Amarapura Chapter frequently visited him. Ven. Meedeniye Wimalananda Thera was one such bhikkhu who always chatted with my father in our house. These people are mostly from ‘Athakasa’ (Youth Poetry Circle in the Capital) and ‘Samastha Lanka Kavi Sammelanaya’ (All Ceylon Poetry Congress). My father was a member of both these poetry circles though he didn’t hold any special posts in them. The hallmark of these people was that they all took their literary movement as their own life. It was the spirit of their art.

Q: Have you seen veteran poets such as P.B. Alvis Perera, Meemana Premathilake or Manawasinghe visiting your home?

A: No, but they had come to see my father before I was born or when I was an infant. I was born in 1959.

Q: Have your father accompanied you to his friends’ houses?

A: I remember he took me to some of his friends’ funerals. For instance, he took me to the funeral of veteran poet H.M. Kudaligama. I also remember my mother accompanied me to the funeral of Mahagama Sekara. At the moment, his body is kept at Heywood.

Q: Impromptu poems or spontaneous verse were very much popular those days. Have you ever seen them improvising impromptu poems?

A: Yes, I saw them improvising impromptu poems, but my father could not sing or chant. So he just listened when others started singing or chanting poems. He especially loved to hear poems by Ananda Rajakaruna, Piyadasa Sirisena and Ven. S. Mahinda Thera from Tibet. When his friends visited our home, sometimes they were engaged in serious literary discussions. I can recall a veteran broadcaster and lyricist Karunrathne Abeysekara mama (we called his friends ‘mama’ instead of uncle) brought me peanuts and chickpeas when he came to our house.

Q: Were there any members from the Peradeniya School of Literature who visited him?

A: Arjuna Parakrama and P. Velikala came to see my father, but others of that school did not come. However, he could associate with some Peradeniya members when they met at Radio Ceylon. – My father worked there.

Particularly, he met Prof. Ediriweera Sarachchandra and Dr. Sunanda Mahendra at Radio Ceylon.

Q: Has your father influenced you?

A: Yes, very much. Right from my childhood days, our house was filled with books, newspapers and magazines. Here I should recall that my father had a printing press titled Subhani in Borella. It was established in the premises of Thilakaratnaramaya in Borella where we lived for a while. The Borella Susamayawardhsane School was also in the temple premises in Austin Place. In fact, my father had hired the temple premises to start his printing press, Subhani which was a popular press some 60 years ago. So many books and newspapers including progressive publications of JVP were published there.

During the JVP insurrection in 1971 my father was summoned to the CID too because of these publications. When he started the press, Pradeepa Publications by K. Jayathilake was also not opened yet.

Anyway, the thing I want to say is that thanks to my father’s press our house was filled with so many books and publications which enabled us to read. And Ven. Rathgama Sumanananda Thera, the chief incumbent of the Thilakaratnaramaya Temple and my father’s close friend often visited our place.

When they got together they discussed various literary and academic issues. All of these things have influenced me.

Q: Your father might have a big personal library?

A: Definitely, he had a large library. Books of six - seven languages, such as Sinhala, English, Pali, Sanskrit, Hindi and Vanga, were in it. He used these foreign languages to read books rather than to speak with.

Q: Has he studied in India?

A: My mother, Kalyani Abhayasundara, studied music in Bhathkande University. She actually learnt playing harp in it. Father did not go to India for studying, but for escorting my mother to the university. However, he had a sensibility to the music and later published a book titled ‘Sangeetha Sanhitha.’ This book was, in fact, a result of his helping hand to my mother who was studying music in India - he helped her with notes on music.

Q: Your mother, Kalyani Abhayasundara was a talented singer at Radio Ceylon. Your thoughts?

A: She had a very melodious voice. She could recite poetry and chant Pirith sweetly. Each day by 6.30 after worshiping Lord Buddha, she chanted a lengthy sermon (Pirith) in a loud, but melodious voice. We all sat with her at those occasions.

As a singer she sang songs with some of the most talented male singers of that time. For instance, she sang with one such singer named Jinadasa Gunasekara, the brother of veteran actor Piyadasa Gunasekara. It was because of him, my father had a chance to write songs for gramophone records. The first songs he wrote for gramophone records were ‘Dharma raja namami ma’ and ‘Dola langa guru para dige’ in 1952. These songs with my mother’s songs are preserved in the Sri Lanka Broadcasting Corporation.

Q: Was your father a religious person?

A: My father was consecrated as a bhikkhu in his early days, but later he had to leave it due to various reasons. In fact, he learnt oriental languages during that time, and passed the Pundit examination with an honours degree. In terms of religion, he considered it not as a way of daily practice, but as a philosophy. So, though he had a great faith in Buddhism, he did not practice its rituals daily.

Q: Your mother and father came from completely different provinces in the country?

A: My father was from Ahungalla, Galle while my mother was from Gothatuwa, Colombo. I actually don’t know how they met.

Q: Do you think your mother’s role as a singer was subdued after the marriage?

A: Not subdued, she abandoned her music career after marrying my father. She thought it was better to look after her children and husband than pursuing music.

Q: Once your father helped to publish a poetry magazine?

A: Not one magazine, but many. And they are, in fact, newspapers rather than magazines. The poetry magazine you mentioned is ‘Kaviya’ (poem).

Poets such as P. Malalgoda, Watareka Premadasa gathered in our house for publishing this magazine. They all worked on news prints (‘Demai papers’) stretched on the ground, and my mother naturally treated them with snacks. They gathered at my home because the press was at our house. During the JVP insurrection in 1971, my father was arrested by the CID.

The reason was he published JVP publications. However, as I recall these memories, I feel they thoroughly enjoyed the moments of publishing. In fact, they did them just for their satisfaction, not for earning money. They were not wealthy, they spent their earnings for the sake of their art.

Q: You know, a great part of poetry in Colombo School of Poetry, are shallow and artificial. Do you know what your father thought about that?

A: He did not criticise works of Colombo School of Poetry. He accepted there were shallow poems in that movement, but instead of criticising them, he himself tried to write serious poetry. When creating poetry, he always focused on the language. He considered language was superior. As he had excelled in Sanskrit Language, he could create a unique poetic language separated from the language of the Colombo School of Poetry. He merged the refined language and the depth of meaning. Some of his poems embody nuances which we still cannot solve.

Q: He denounced the free verse?

A: Yes, he denounced that movement. Free verse had flourished in the University of Peradeniya, which was one reason that he went against the Peradeniya school of literature. And on the other hand, he had some relationship with Munidasa Kumarathunge through his ‘Subasa’ magazine. My father, Prof. Vini Vitharana, Gunapala Senadira, Hemapala Munidasa, Vevi Abhayagunawardhane, all wrote to the ‘Subasa’ magazine. However, he associated with some members of the University of Peradeniya. For instance, Prof. D.E. Hettiarachci was one his friends. He could associate with him when he was working at the encyclopedia as an assistant editor. And though Mahagama Sekara was a follower of free verse, father kept company with him and his poetry as well. I think, as a member of the ‘Athakasa’ and All Ceylon Poetry Congress he tried to protect their poetry tradition.

Here I would like to highlight another point. You know, my father and many others in his poetry movement worked for the refined language. The value of their efforts clears for us when we think about the present situation.

I know as a lecturer, we were advised to teach graduate students in English.

I am not opposed to English, it is very important as a tool. But switching to English totally neglecting our mother tongue is a sad thing, because the excellence of our classical traditional literature is something you cannot experience from any other language. You can understand this if you read some traditional classics such as Buth Sarana, Ama Watura, Kav Silumina and Sigiri Gee. When thinking about nowadays university education, I feel future students will be deprived of the knowledge of our traditional classics. This is not only a catastrophe for Sinhala language, but the Tamil language as well.

My father was someone who always stood for values and standards at Radio Ceylon. Once, at a literary gathering, veteran singer Victor Rathnayake said that my father had censored one of his songs – it was the song, ‘Malvara Nekathin Dorata Wadina Sanda ….. Sina Malak Wan Sina Malee.’ It was written by veteran lyricist Kularathne Ariyawansha. But after referring it later in life, especially after he had his own daughters, Victor Rathnayake said, my father was correct, because there are some aspects in our culture that we should not express through art.

My father always prompted me to write meaningful songs. He censored even my songs in the radio when they were not up to the standard. He had been working for a long time as a panel member who judged the standard of Sinhala songs. Their parameters for selecting songs for broadcasting were language, culture, nation, religion and country. I remember some panel members such as K. Francis, M.A.M. Mohommed visited our house those days. Mohommed was a judge for Muslim programs while Francis was a judge for Christian programs.

Though they were from different religions and cultures, they tried their best to present standard programs to listeners. His final aim was to build up a cultural life for people. Now all has been upended.

Q: What are the guidelines he gave you in terms of writing?

A: He urged me to write for newspapers, but creatively. He also taught me the correct use of language in writing. He directed me to read books and learn new words as well. He never forced me to do anything, but showed us what to do in his own behaviour. You know, he lived with books, reading and writing.

So, it was not necessary to advice us to read and write. When the literature month reached, he took us to bookshops in Maradana and the Gunasena Book Shop.

There he did not select books for us, but left us to select them ourselves.

Some of father’s friends who worked at those bookshops presented us books as gifts during those visits.

For instance, the late veteran writer Lal Premanath de Mel who was working as a publishing manager at the Gunasena Book Shop, gave us some other books as gifts. Veteran writer K. Jayathilake also gifted us books with his signature from his own bookshop, Pradeepa Prakashakayo, at Aluthkade Court Complex Road.

Besides these, he also urged me to learn foreign languages, especially Pali and Sanskrit. But I couldn’t learn them as he wished.

Q: Your father seriously took the technical aspect of poetry making as with his other counterparts in the Colombo School of Poetry?

A: When he was producing poetry programs like ‘Padyavali’ at Radio Ceylon, he rejected broadcasting poor poems. After rejecting them, some fans asked him through letters what were the shortcomings in those poems. Sometimes he replied them, but most of the time he personally pointed out the shortcomings of them. He described them the art of poetry very seriously. I even cannot understand some of his techniques.