Today is International Day for Biological Diversity (IDB). It was created by the Second Committee of the UN General Assembly on December 29, 1993, (the date of entry into force of the Convention of Biological Diversity). In December 2000, the General Assembly adopted May 22 as IDB. The purpose of it is to increase understanding and awareness of biodiversity issues.

However, today’s world is not a better place for biodiversity as it is rapidly declining. Virtually in every country that decline happens, and it is much worse in third world countries. For instance, Brazil’s Amazon forest is disappearing far more than predicted: nearly a fifth of the forest has lost already.

Scientists believe that tipping point will be reached at 20 to 25 percent of deforestation. The Amazon is 10 million years old, and a home to 390 billion trees. Its vast river basin reigns over South America and is an unrivaled nest of biodiversity. According to the Time article by Matt Sandy, from blue morpho butterflies to emperor tamarins to pink river dolphins, biologists find a new species from there every other day.

Satisfying news

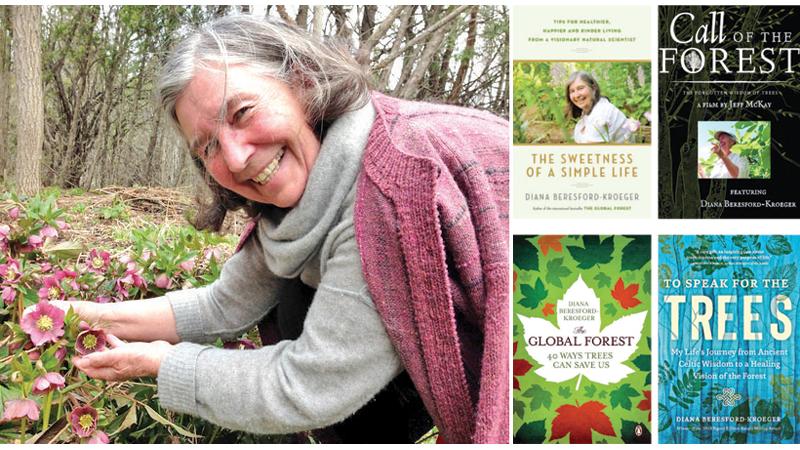

While we always hear about these kinds of gloomy pictures from the world, very rarely some pleasing news also reach us from the same world. The story of Canadian author, botanist and environmentalist Dr. Diana Beresford-Kroeger is such delightful news. She has created a forest with tree species handpicked for their ability to withstand a warming planet. She lives in the woods of Canada, in a forest she helped grow. As reported by Cara Buckley for The New York Times (NYT) on February 24, wielding just a pencil, she has been working to save some of the oldest life-forms on Earth by bewitching its humans.

The 77-year-old botanist is not only an author and botanist, she is also a medical biochemist, organic chemist, poet and developer of artificial blood. But her main focus for decades now has been to telegraph to the world, in prose that is scientifically exacting yet startlingly affecting, the wondrous capabilities of trees.

The New York Times reported that Dr. Beresford-Kroeger’s goal is to combat the climate crisis by fighting for what’s left of the great forests (she says the vast boreal wilderness that stretches across the Northern Hemisphere is as vital as the Amazon) and rebuilding what’s already come down. Trees store carbon dioxide and oxygenate the air, making them “the best and only thing we have right now to fight climate change and do it fast,” she said to the NYT journalist Cara Buckley.

Upbringing

Her full name is Diana Bernadette Beresford-Kroeger, and was born on July 25, 1944, in Islington, England. She is an Irishwoman, but now lives near Ottawa, Ontario, Canada. As per facts at the Wikipedia, she is known for her ability to bring an understanding and appreciation of the scientific complexities of nature to the public. In the foreword to one of her books, ‘Arboretum America, a Philosophy of the Forest’, E. O. Wilson wrote, “Diana Beresford-Kroeger is one of the rare persons who can accomplish this outwardly simple but inwardly complex and difficult translation from the non-human to human realms”.

At 12, she was orphaned, because her father, an English aristocrat, died under mysterious circumstances, while her mother, who traced her lineage to ancient Irish kings, died in a car crash. Thereafter, she was taken in by a kindly if neglectful uncle in Cork. This bachelor uncle, Patrick O’Donoghue was a noted athlete, chemist, scholar, and bibliophile. He nurtured her quest for knowledge and encouraged her to read and discuss everything from Irish poetry, world religions, and philosophy, to physics and quantum mechanics. And during the summers, she spent time with Gaelic-speaking relatives in the countryside in West Cork and Kerry, which was where she received the lessons of her folk lineage.

The schools she attended were private ones in Ireland and England. And, one of her maternal grandaunts taught her ancient Irish ways of life known as the Brehon laws. There she learned that in Druidic thinking, trees were viewed as sentient beings that connected the Earth to the heavens. She was also versed in the medicinal properties of local flora: Wildflowers that warded off nervousness and mental ailments, jelly from boiled seaweed that could treat tuberculosis, dew from shamrocks that Celtic women used for anti-aging.

Higher education

Dr. Beresford-Kroeger didn’t set out to be an outlier. She finished her undergraduate studies at University College Cork in Ireland, where she studied botany and biochemistry. She graduated in 1963 with a Bachelor of Science honours in botany and medical biochemistry. In 1966, she moved to America to research organic and radio-nuclear chemistry at the University of Connecticut, from which she took a Master of Science degree. There her thesis was: “Frost Resistance and Gibberellins in the Plant Kingdom.”

Three years later, she moved to Canada to study plant metabolism at Carleton University, and then did cardiovascular research at the University of Ottawa, where she began working as a research scientist in 1972. She received her Ph.D. in biology from Carleton University in 2019. Her thesis was entitled, ‘Myocardial Ischemia and the use of non-typing artificial blood in hemodilution’.

After she came to Canada, she faced sexism, harassment and, in that part of Loyalist Canada, anti-Irish sentiment. Therefore, in 1982 she left academia, as much repelled by the toxicity as she was drawn to a deeper calling, rooted in a childhood that was both Dickensian and folkloric.

Practising knowledge

As a graduate student, a few years later, Dr. Beresford-Kroeger put the teachings she learned to the scientific test and discovered with a start that they were true. Cara Buckley writes:

“The wildflowers were St. John’s Wort, which indeed had antidepressant capacities. The seaweed jelly had strong antibiotic properties. Shamrocks contained flavonoids that increased blood flow. This foundation of ancient Celtic teachings, classical botany and medical biochemistry set the course for Dr. Beresford-Kreoger’s life. The more she studied, the more she discovered that the symbiosis between plants and humans extended far beyond the life-giving oxygen they produced.”

In her most recent book, “To Speak for the Trees” Dr. Beresford-Kroeger writes: “Every unseen or unlikely connection between the natural world and human survival has assured me that we have very little grasp of all that we depend on for our lives. When we cut down a forest, we only understand a small portion of what we’re choosing to destroy.”

Deforestation, she said, was a suicidal, even homicidal, act.

“We’ve taken down too much forest, that’s our big mistake,” Dr. Beresford-Kroeger said during a recent chat in her hand-built home, as her husband, Christian Kroeger, puttered in the kitchen, making lunch. “But if you build back the forests, you oxygenate the atmosphere more, and it buys us time,” she was quoted in the NYT.

Difference

Dr. Beresford-Kreoger is a different character right from the outset. According to the late biodiversity pioneer E.O. Wilson, what sets Dr. Beresford-Kreoger apart is the breadth of her knowledge. NYT journalist Cara Buckley writes:

“She can talk about the medicinal value of trees in one breath and their connection to human souls in the next. She moved Jane Fonda to tears. She inspired Richard Powers to base a central character of his Pulitzer-prize winning novel, ‘The Overstory,’ in part on her: he has called her a “maverick” and her work “the best kind of animism.”

Among her cultivations was an arboreal Noah’s Ark of rare and hardy specimens that can best withstand a warming planet. She said to NYT that the native trees she planted on her property in this rural village sequester more carbon and better resist drought, storms and temperature swings, and also produce high quality, protein-rich nuts.

“If industrial logging continues to eat away at forests worldwide, soil fertility will plummet, and Dr. Beresford-Kroeger, an Irishwoman, is haunted by the prospect of famine.” NYT reported.

Independent researcher

Dr. Beresford-Kroeger is mainly an independent researcher, unaffiliated with any institution. Her main source of income is royalties of her writings and the sale of her rare plants. Why didn’t she work as a permanent employee? It was because she wanted freedom to study and spread her ideas without any strictures. Ben Rawlence, an English writer, said of her: “Often these kinds of brilliant pioneers are outliers who don’t play by the rules.”

While researching his new book ‘The Treeline: The Last Forest and the Future of Life on Earth’, Ben Rawlence found himself “sitting at her feet doing a master’s in the boreal forest packed into three days.”

“People like her are very important,” he said. “They can integrate the depth of different disciplines into a total picture.”

Life in wilderness

Now the Beresford-Kroegers live south of Ottawa, down a long country lane on a 160-acre parcel of land they bought decades ago. According to the NYT reporter, their house is filled with well-thumbed books, fingers of sunlight, thriving plants and Boots, their rescue cat. She writes all of her papers and books by hand, and doesn’t have a smartphone or computer or any social media accounts. When she needs to Zoom, she pops down to the local library and uses a public desktop.

NYT report mentions that outside the house, her treasured trees grow, all climate-change resistant to varying degrees: the kingnut, a blue-needled fir and a rare variant of the bur oak. She began creating her arboretum after learning that many key tree species prized by First Nations people for medicines, salves, oils and food had been razed by colonisers centuries ago. “These trees have fed the continent before in the past,” she said to Cara Buckley for the NYT. “I want them available there for people in the future.”

Home-made forest

It is reasonable to think that home-made forest or repatriated forest is an impossible output. But if you have the will and dedication, it is not such difficult. The classic example for it is Dr. Beresford-Kroeger’s 160-acre home forest. Over the years, she painstakingly tracked down, across the continent and beyond, rare seeds and saplings native to Canada. “I thought, ‘Well I’m going to repatriate these trees,’” she said. “I am going to bring them back to here, where I know they’re safe.”

She also knew if the “repatriated” plants and trees were shared far and wide, they’d no longer be lost. So the NYT journalist Cara Buckley describes:

“She and Christian began giving away native seeds and saplings to pretty much anyone who asked. Among the tens of thousands of recipients were local Hell’s Angels, who roared up to their doorstep to collect black walnut seedlings, wanting to grow the valuable trees on their property nearby.”

“I put them in the back of their motorcycle, their Harley-Davidsons,” she said to NYT. “I thought I’d die of a heart attack. But they were very nice to me.”

Writing life

Dr. Beresford-Kroeger started writing when she was in her forties. Yet it took a decade to find a publisher for her first manuscript. However, she has since published eight books, and at least a couple of them Canadian best sellers. One was about holistic gardening, another about living a pared-down life. But her main focus was the importance of trees.

As she is a botanist who loves trees, she always writes about the irreplaceability of the boreal forest, which principally spans eight countries, and “oxygenates the atmosphere under the toughest conditions imaginable for any plant.”

According to the NYT, through her books she introduces her “bioplan”: If everyone on earth planted six native trees over six years, she says it could help mitigate climate change. She wrote about how a trip to the forest can bolster immune systems, ward off viral infections and disease, even cancer, and drive down blood pressure.

Still there isn’t a rosy road for Dr. Beresford-Kroeger to travel in the publishing world. As she recounts, one publisher admonished her for being a scientist who described landscapes as sacred. The head of a foundation, while introducing her following a screening of “Call of the Forest,” a documentary about her life, let slip that he didn’t believe a word of what she said.

Insights

The uniqueness of Dr. Beresford-Kroeger is that she could combine modern scientific knowledge with her intrinsic traditional knowledge. Therefore, she could offer new insights for any natural phenomenon. Bill Libby, an emeritus professor of forest genetics at the University of California, Berkeley, also describes her talent. He initially had reservations when Dr. Beresford-Kroeger offered a biological explanation for why he felt so good after walking through redwood groves. There she attributed his sense of well-being to fine particles, or aerosols, given off by the trees.

“She said the aerosols go up my nose and that’s what makes me feel good,” Dr. Libby said.

Outside research has also supported some of her claims. Cara Buckley says that studies led by Dr. Qi Ling, a physician who coedited a book for which Dr. Beresford-Kroeger was a contributor, found visits to forests, or forest bathing, lessened stress and activated cancer-fighting cells. A 2021 study from Italy suggested that lower rates of Covid-19 deaths in forested areas of the country were linked in part to immunity-boosting aerosols from the region’s trees and plants.

“I was laughed at until fairly recently,” Dr. Beresford-Kroeger said, her Irish accent still strong. “People all of a sudden seem to be waking up.”

Present demand

Nowadays, Dr. Beresford-Kroeger is in great demand, because people are more aware of mounting fears about the environment and a hunger for solutions. So, in 2019, Carleton University awarded her a doctorate in biology along with an honorary doctor of law degree for her climate work. The next year, she was a guest on one of Jane Fonda’s televised climate action teach-ins.

NYT describes she regularly delivers virtual talks to universities and keynote addresses to organisations (“I had goose bumps talking to her,” said Susan Leopold, the moderator of her talk at the 2021 International Herb Symposium). She is helping to plan medicinal healing gardens in Toronto and outside Ottawa as she finishes a new book about how people are spiritually connected to nature. “The publishers can like it or bloody lump it,” she said.

Cara Buckley said that during a tour of her forest and gardens, Dr. Beresford-Kroeger spoke with wonder about how ancient Celtic cures were almost identical to those of Indigenous peoples, and waxed poetic about the energy transfer from photons of sunlight to plants’ electrons during photosynthesis.

Then she advised a reporter to lean against a tree before writing. People, she said to Buckley, should look at forests as “the sacred center of being.”

“Without trees, we could not survive,” she said. “The trees laid the path for the human soul.”