Dalí was born in Figueres, a small town outside Barcelona, to a prosperous middle-class family. The family suffered greatly before the artist's birth, because their first son (also named Salvador) died quickly.

The young artist was often told that he is the reincarnation of his dead brother - an idea that surely planted various ideas in the impressionable child. His larger-than-life persona blossomed early alongside his interest in art. He is claimed to have manifested random, hysterical, rage-filled outbursts toward his family and playmates.

The young artist was often told that he is the reincarnation of his dead brother - an idea that surely planted various ideas in the impressionable child. His larger-than-life persona blossomed early alongside his interest in art. He is claimed to have manifested random, hysterical, rage-filled outbursts toward his family and playmates.

From a very young age, Dalí found much inspiration in the surrounding Catalan environs of his childhood and many of its landscapes would become recurring motifs in his later key paintings. His lawyer father and his mother greatly nurtured his early interest in art. He had his first drawing lessons at age 10 and in his late teens was enrolled at the Madrid School of Fine Arts, where he experimented with Impressionist and Pointillist styles. When he was a mere 16, Dalí lost his mother to breast cancer, which was according to him, "the greatest blow I had experienced in my life." When he was 19, his father hosted a solo exhibition of the young artist's technically exquisite charcoal drawings in the family home.

His mature days

In 1928, Dalí partnered with the filmmaker Luis Buñuel on Un Chien Andalou (An Andalusian Dog), a filmic meditation on abject obsessions and irrational imagery. The film's subject matter was so sexually and politically shocking that Dalí became infamous, causing quite a stir with the Parisian Surrealists.

The Surrealists considered recruiting Dalí into their circle and, in 1929, sent Paul Eluard and his wife Gala, along with René Magritte and his wife Georgette, to visit Dalí in Cadaques. This was the first time Dalí and Gala would meet and shortly after the two began having an affair which eventually resulted in her divorce from Eluard.

Gala, born in Russia as Elena Dmitrievna Diakona, became Dalí's lifelong, constant, and most important muse, as well as being his future wife, his greatest passion, and his business manager. Soon after this original meeting, Dalí moved to Paris, and was invited by André Breton to join the Surrealists.

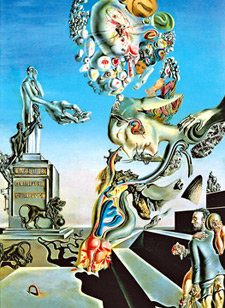

Dalí ascribed to Breton's theory of automatism, in which an artist stifles conscious control over the creative process by allowing the unconscious mind and intuition to guide the work. Yet in the early 1930s, Dalí took this concept a step further by creating his own Paranoic Critical Method, in which an artist could tap into their subconscious through systematic irrational thought and a self-induced paranoid state.

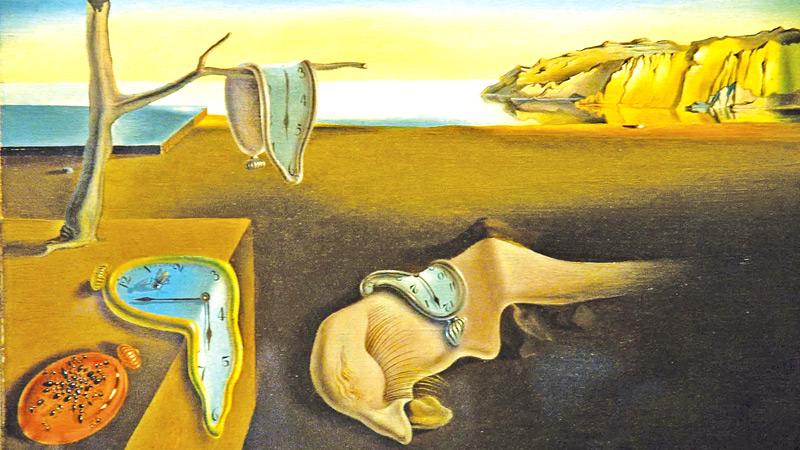

After emerging from a paranoid state, Dalí would create "hand-painted dream photographs" from what he had witnessed, oftentimes culminating in works of vastly unrelated yet realistically painted objects (which were sometimes intensified by techniques of optical illusion).

He believed that viewers would find intuitive connection with his work because the subconscious language was universal, and that, "it speaks with the vocabulary of the great vital constants, sexual instinct, feeling of death, physical notion of the enigma of space - these vital constants are universally echoed in every human." He would use this method his entire life, most famously seen in paintings such as The Persistence of Memory (1931) and Soft Construction with Boiled Beans (Premonition of Civil War) (1936).

For the next several years, Dalí's paintings were notably illustrative of his theories about the psychological state of paranoia and its importance as subject matter.

He painted bodies, bones, and symbolic objects that reflected sexualised fears of father figures and impotence, as well as symbols that referred to the anxiousness over the passing of time. Many of Dalí's most famous paintings are from this highly creative period.

While his career was on the rise, Dalí's personal life was undergoing change. Although he was both inspired and besotted by Gala, his father was less than enthused at this relationship with a woman ten years his son's senior. His early encouragement for his son's artistic development was waning as Dalí moved more toward the avant-garde.

The final straw came when Dalí was quoted by a Barcelona newspaper as saying, "sometimes, I spit for fun on my mother's portrait." The elder Dalí expelled his son from the family home at the end of 1929.

The politics of war were at the forefront of Surrealist debates and in 1934 Breton removed Dalí from the Surrealist group due to their differing views on communism, fascism, and General Franco. Responding to this expulsion Dalí famously retorted, "I myself am Surrealism."

For many years Breton, and some members of the Surrealists, would have a tumultuous relationship with Dalí, sometimes honouring the artist, and other times disassociating themselves from him. And yet other artists connected to Surrealism befriended Dalí and continued to be close with him throughout the years.

In the following years, Dalí travelled widely, and practised more traditional painting styles that drew on his love of canonised painters like Gustave Courbet and Jan Vermeer, though his emotionally charged themes and subject matter remained as strange as ever.

His fame had grown so widely that he was in demand by the rich, well known, and fashionable. In 1938, Coco Chanel invited Dalí to her home, "La Pausa," on the French Riviera where he painted extensively, creating work later exhibited at the Julien Levy Gallery in New York.

But undoubtedly, Dalí's true magic moment came that year when he met his hero, Sigmund Freud. After painting his portrait, Dalí was thrilled to learn that Freud had said, "So far, I was led to consider completely insane the Surrealists, who I think I had been adopted as the patron saint. This young Spaniard with his candid, fanatical eyes and his undeniable technical mastery has made me change my mind."

Around this time Dalí also met a major patron, the wealthy British poet Sir Edward James. James not only purchased Dalí's work, but also supported him financially for two years and collaborated on some of Dalí's most famous pieces including The Lobster Phone (1936) and Mae West Lips Sofa (1937) - both of which decorated James' house in Sussex, England.

The legacy of Salvador Dalí

Dalí epitomised the idea that life is the greatest form of art and he mined his with such relentless passion, purity of mission and diehard commitment to exploring and honing his various interests and crafts that it is impossible to ignore his groundbreaking impact on the art world.

His desire to continually and unapologetically turn the internal to the outside resulted in a body of work that not only evolved the concepts of Surrealism and psychoanalysis on a worldwide visual platform but also modeled permission for people to embrace their selves in all our human glory, warts and all.

By showing us visual representations of his dreams and inner world laid bare, through exquisite draftsmanship and master painting techniques, Dalí opened a realm of possibilities for artists looking to inject the personal, the mysterious and the emotional into their work.

In post-war New York, these concepts were incorporated and transformed by Abstract Expressionists who used Surrealist techniques of automatism to express the subconscious through art, only now through gesture and colour.

Dalí's use of wildly juxtaposing found objects to create sculpture helped shake the medium from its more traditional bones, opening the door for great Assemblage artists such as Joseph Cornell. Today, we can still see Dalí's influence on artists painting in Surrealist styles, others in the contemporary visionary arts spheres and all over the digital art and illustration spectrums.

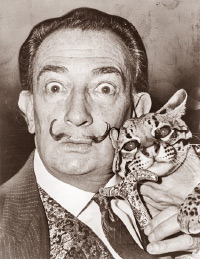

Dalí's physical character in the world, eccentric and enigmatic, paved the way for artists to think of themselves as brands. He showed that there was no separation between Dalí the man and Dalí the work.

His use of avant-garde filmmaking, provocative public performance and random, strategic interaction brought his work alive in ways that differed from the painting - instead of the viewer merely looking at a beautiful work that evoked great imagination, they would be "poked" in real life by a manifestation of Dalí's imagination designed to unsettle and conjure reaction.

This could later be seen in artists like Yoko Ono. Andy Warhol would go on to concoct his own persona, environment and entourage in much the same way as would countless other 20th-century artists. In today's social-media landscape, artists are almost expected to be visibly and socially just as interesting as their art work.

Dalí also spearheaded the idea that art, artist and artistic ability could cross many mediums and become a viable commodity.

His exhaustive endeavours into fields ranging from fine art to fashion to jewelry to retail and theatre design positioned him as a prolific businessman as well as creator. Unlike mass merchandising, which is often disdained in the art world, Dalí's hand touched such a variety of products and places, that literally anyone in the world could own a piece of him.

Today this practice is so common that we find great architects like Frank Gehry designing special rings and necklaces for Tiffany or innovators like John Baldessari lending his images to skateboard decks.

Courtesy: The art story