We feature below a detailed interview with heritage specialist Prof. Nimal de Silva covering many topics of national interest, including the potential for a traditional and indigenous knowledge based model of Lankan unity and prosperity as opposed to Western influenced constructs of peace building.

He says that the ancient Sinhala civilisation was the epitome of tolerance of different cultures and that it was never founded on ethnic based violence or plunder as the Western experience.

He argues that the same pre- colonial values of the Sinhala civilisation could be used today to bring all Lankans together respecting both Buddhistic and pre-Buddhistic beliefs that inter-connect Hindu based and Buddhist centric value systems of this nation.

He also explains the Lankan roots that the early Muslim traders who settled in this country absorbed and how they were loyal to the country which they adopted as their own which is the motherland of their offspring today. He thus believes that heritage could be one of the greatest connectors for a stable nation.

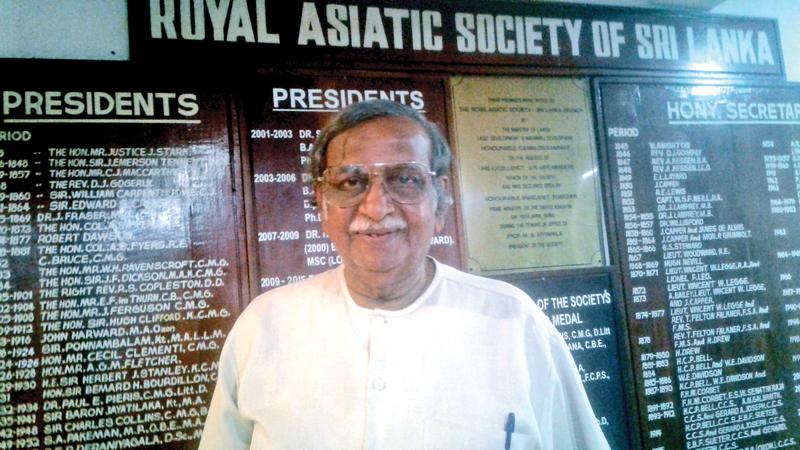

Prof. Nimal de Silva has held many prestigious positions such as being the Director of the Postgraduate Institute of Archaeology and supervised many PhD. programs on Archaeology and Traditional Heritage. He was instrumental in initiating a postgraduate program on heritage studies.

Prof. Nimal de Silva has held many prestigious positions such as being the Director of the Postgraduate Institute of Archaeology and supervised many PhD. programs on Archaeology and Traditional Heritage. He was instrumental in initiating a postgraduate program on heritage studies.

He has served as the Senior Professor in the Faculty of Architecture in the University of Moratuwa, and was Director for the Centre for Heritage and Cultural Studies as well as the National Design Centre.

As Chairman of the Urban Development Authority (UDA) for nearly four years he initiated the declaration of Colombo Fort as a conservation area.

As Chairman of the National Design Centre, he promoted traditional craft persons and their skills, drawing on his inherited in-depth knowledge on arts and crafts. He is currently supporting Lankans who want to promote traditional knowledge amongst citizens within the country and abroad for both national prosperity and unity.

He has served as the Director Conservation in UNESCO Sri Lanka Project of the Cultural Triangle. Pertaining to the Maligawa Complex in Kandy he was responsible for the conservation of related historic buildings, the Devala Complex and the Malwatta Vihara and Asgiriya Vihara Complex.

He has extensively used Sri Lankan heritage for promoting cultural cohesiveness. He has authored over 20 books relating to Lankan culture and heritage, including on Flags of Sri Lanka, landscape tradition, ancient pottery, heritage buildings, on Kandy – as a cultural guide to the world heritage city, indigenous trees for traditional landscape of Sri Lanka and the latest series which is a Sinhala edition include handbooks on mats in the Sinhala weaving tradition, clay pots, pus kola poth and Sinhala tradition of flags and art.

In this interview he covers many points connected to culture, history and heritage based knowledge and its relevance to the present for the upholding of national economic independence, permanent peace and national self-respect.

He says that acquiring all three aspects are primarily connected with how sound Lankan policymakers are with their cultural roots to be able to steer policies for national wellbeing and thereby avoid dependency.

Following are excerpts:

Q: What are your current priorities?

A. I have just finished writing a series of books in Sinhala connected with the Sinhala tradition of mat weaving, clay pots, Sinhala tradition of flags, art and pus kola poth. They are five books in all. I have just taken over as the Librarian of the Royal Asiatic Society of Sri Lanka (RASL) which is located at the Mahaweli Centre. I am trying to find ways to help the general public make use of this library.

It has some of the best works connected to not only Lankan but also South Asian Heritage. The RASL journals the library has contain very rich information connected to beliefs, customs and knowledge connected to Lanka written by many scholars and practitioners.

I am trying to work with several people to ensure that some of this knowledge gets transferred to Lankan youth and that practical skills such as mat which is available as theoretical book knowledge, is transmitted more to the public. Skills such as these are almost fully wiped out from society and this has cost the rural economy much. Libraries should be stimulating places where knowledge is transferred towards practical objectives. I am trying to make the RASL library this.

Q: How would you describe the word ‘heritage’?

A. Heritage means all what you have inherited from earth – from the location in this planet that is – which we call our motherland to your personal genes. Heritage has two basic parts; natural heritage and cultural heritage. Cultural heritage is also divided into two as intangible and tangible. Heritage, both tangible and intangible equals knowledge.

All tangible heritage objects are created to support and fulfill intangible heritage requirements. Tangible heritage can be movable or immovable. Each monument we have as tangible heritage is linked to the intangible – such as different forms of knowledge associated with different aspects of the human civilisation of each country.Our nation has a very vast realm of knowledge in this regard and this is what made ancient Sri Lanka a very independent, economically stable, respected country.

This was because the king and the advisers of the king administered the country based on this knowledge. They were not alien to it. Sustaining the traditional knowledge emanating from national heritage could range from agrarian knowledge, soil conservation techniques and various aspects of maintaining the wellbeing of a country and people.

This knowledge transfer and use is connected to the thousands of Ola leaf manuscripts we have in the country. Some of it was plundered and taken away by the colonists but many of these are remaining in Sri Lanka.

Much of these ancient knowledge repositories are falling apart in very bad condition. We do not know or care or want to use for practical results the knowledge that is in them. More and more we are losing people who know how to interpret this knowledge.

Preserving and using the information explained in these ancient records are directly connected to preserving the self respect of a nation by enabling it to be self-sufficient and self reliant. Instead, since independence we have had the malady of looking to other nations for the expertise we need, whether it is engineering or architecture or related to health. We are a hydraulic civilisation cut away from its roots because of our post colonial ignorance.

In Sri Lanka we have the engineering feats of our Buddhist Chaithyas associated with a gamut of knowledge such as ancient technology of safeguarding premises from lightning. Another example of how the tangible heritage is linked with the intangible is that of the Mihinthale Hospital in Sri Lanka considered to be the oldest hospital in the world linked to the Buddhist civilisation of this country.

There are many academic papers written on the archeological findings of the ancient medical instruments, especially related to surgery and sanitation. The knowledge connected with this, connected to the medical science of the Sinhala civilisation (Sinhala Wedakama) which is linked to the overall Ayurveda tradition which emanated in India but uniquely developed in Sri Lanka was shaped according to local resources, culture and traditions.

Q: Could you elaborate more on the traditional Lankan knowledge that you grew up with?

A. Yes, I grew up in the South of the country (Boossa) surrounded with diverse forms of knowledge, especially that connected to local medical science. For us this was the most recognised and respected national medical science – Sinhala Wedakama/ Lankan Ayurveda which we used on the rare occasions when we were sick. Our food patterns were such, linked to our indigenous diet that sickness was not common and immunity was not synthetically engineered because agriculture was then still a natural process as ancestrally carried out.

My grandfathers and great grandfathers were Sinhala Vedamahttayas. They treated the sick without any fee. They were given a bulathatha and kevilibandesiya for the New Year. Intangible heritage is all about skills of a civilisation that is in turn connected to its values. Astrology, language, art, music and dance all fall to these categories and these were part of the daily lives of people.

This is the background I grew up in. My maternal great grandfather knew five languages; Sinhala, Pali Sanskrit, Tamil, and English. He knew Sinhala Vedakama, Astrology, Manthra Sasthra and was also a musician who wrote and staged plays.

In the 1870s villagers in the Southern Province started building new Buddhist Viharas creating a great demand for artists to do temple painting for which he established a school of painting with two traditional masters. Heritage scholar, L.T.P. Manjusri has identified them as Welithara Sittara Paramparawas.

Q: How did your childhood influence you in adulthood?

A. My childhood was closely linked with mother nature. I grew up listening to Sinhala lullabies and nursery rhymes being sung to us by my mother, grandparents and aunties. These lullabies had both beauty and wisdom which is deeply ingrained into the psyche of the infant when sung which can connect a child to the root of a particular culture.

Today I don’t think any young mother even knows these.

The health I enjoy today is linked to the practice which we had as children in consuming our traditional diet -where every day morning – we had to take lunukenda before having any breakfast. On the very few occasions sickness overcame us, my parents called Piyasiri Vedamahattaya, one of our relatives who was the last one in our family to practice traditional medicine.

He never asked for a fee and whatever our parents gave he accepted without even looking at what was offered. Through this we learnt the non materialistic values of Buddhist kindness and compassion – where healing another was about accruing good karma.

Overall, my parents knew all basic treatments. My mother was an expert at this and she would narrate the Sinhala poetic version of how the cure is described traditionally when administering the cures. We learnt these from her.

It was part of general education of the housewife and adults to be able to prevent and permanently cure (nittawata suwakireema) diseases early after identification; diseases which now require expensive and lifetime medication from the Western system.

One such simple method Sri Lankans knew concerning the prevention of heart blocks was with few herbs used as a ‘pottaniya’ to ferment the chest area.

So the kind of childhood I had (and that of most in my generation) could actually be described as a detailed course in intangible cultural heritage, covering many criteria of traditional knowledge and passed on by our elders. This is my background as a Sinhalese but for a Sri Lankan Tamil, Muslim or Burgher this knowledge would vary but be rooted in Sri Lanka within his or her ethnic based cultural parameters and be connected to the history of Sri Lanka.

Q: Why have we been incapable of preserving our traditional knowledge?

A. Our emotion and our practice have moved away from what we perceive as our heritage. Today we have scholars of ICH and heritage but it has been removed from the psychology of the people because the early childhood is separated from it. Language is a key route in how a child learns and this is rooted to the culture and knowledge of the land.

In a colonial and post colonial background where English was largely considered as a socially prestigious language my family was primarily connected to Sinhala, our mother tongue while also learning English as an international language. Today young people learn English not so much as a language but as a culture. We do not use Western science practically where needed with wisdom but rather worship it.

It is the childhood influence I got which has made me follow my traditional lifestyle to date and made me believe both as a child and adult that the mind and our worldly actions are inter-connected to the final outcome of one’s physical health. As a child I learnt to follow the Dhamma and as an adult in all the official positions I have held I have not taken even a single cent outside my salary.

Preserving our values, traditions and knowledge is therefore very much part of intangible cultural heritage. If we were all practitioners of our traditional values we will not have corruption at high levels in this country.

As a child I learnt to inculcate a peaceful mind and keep awareness at all times on the consequences of each of my actions.

Q: Could you comment on what we should be mindful of today when putting our medical heritage in practice?

A. During the colonial occupation we were brain-washed and convinced that what is Sri Lankan – local or traditional are inferior and no good. They will teach what is good and bad. The elites and the English-educated swallowed it. For any traditional thing to be accepted it has to be proved to the West using Western science. Inguru, Kottamalli Veniveigeta that we used for thousands of years is being analysed even by our universities to prove it to the West. For What?

We were trained and taught to reject and have doubt on our traditional knowledge systems. This is the reason of our downfall and we can see it very well today. The Sinhalese, the Tamils and the Muslims of Sri Lanka have a medical tradition that could greatly help us in times such as these when the Western world knows only vaccines to boost immunity.

We were trained and taught to reject and have doubt on our traditional knowledge systems. This is the reason of our downfall and we can see it very well today. The Sinhalese, the Tamils and the Muslims of Sri Lanka have a medical tradition that could greatly help us in times such as these when the Western world knows only vaccines to boost immunity.

Our solid understanding of our medical heritage should help not only us but a world failing in the synthetic route to medication.

As far as I know Ayurveda and Desiya vedakama are basically based on similar principles. But our Sri Lankan medical system is simple and with a lot of speciality and family based with many variations.

We are yet to do a systematic compilation of traditional medical practices currently prevailing in the country. If we compile our traditional medical systems using all the ancient manuscripts, we would be in a position to create a unique hela medical system. We have not done this for seven decades. We are talking of promoting our tourism through Sri Lankan Ayurveda but we have to first start using our medical heritage for our health challenges at national level.

Q: Could you explain how the ancient concept of the Sinhala civilisation could be used in modern times of today as an alternative to the Western influenced liberal peace building model which has created Western interference as well as dominance and has many INGOs funding different agendas connected to this goal.

A. In my studies I have realised that Sinhala is not just an ethnic group; it is a civilisation. Sinhala is a civilisation. There were non-Sinhala kings who ruled Sri Lanka due to various invasions by Chola, Pandeyas and Kalinga from neighbouring territories. Our kings gave their sisters and daughters in marriage to foreign royalty (India and Malaysia, and so on). The last four Sri Lankan kings were all from India.

King Nissankamalla and Sahasamalla of 12th century were of Kalinga origin – Kalingas extended to Malaysia which was then Buddhist. Also, a significant number of soldiers of neighbouring armies settled in Sri Lanka and some members of our ancient armies which went to fight in those lands also settled in those places.

For example, Eelavam is a social group that had left Sri Lanka around the 13th century and settled in Kerala. They were said to be Singhalese soldiers who were sent by Lankan kings to Kerala to support a Kerala monarch in an internal war effort.

Professionals such as craftsman came here and some of them settled for good. During the Gampola period all the queens were brought from India. Gampola Lankathilaka Vihara and Gadaladeniya Vihara were designed by Indian architects and craftsmen.

Same with the Natha Devala of Kandy and the Adhanamaluwa (cremation ground of Royalty) where all the architecture has Indian influence. Keerthi Shri Rajasinghe of Nayakka dynasty joined the Dalada Perahera with the Devale perahera. Many Sinhala chieftains were against this.

However, we know that this king is credited with the revival of Buddhism and literature in Sri Lanka. It is he who invited bhikkhus from Siam (current day Thailand) to facilitate the renewal of the higher ordination of bhikkhus in Sri Lanka.

What I am trying to say is that whoever came to this land, whether king or commoner, embraced Sinhala as a civilisation. It also has to be said that whatever the interwoven history and close proximity with India, the Sinhalese stood their own as a distinctly separate entity.

They carried forth the Sinhala civilisation (Sinhala) and its identity because this was enshrined within the people of the country which had built up the framework of this civilisation for thousands of years. After Buddhism was introduced to the country, the Dhamma was strongly integrated and carried forth as part of this civilisation.

One must realise the Sinhala language has continuously lasted over 2,300 years. It has lasted with a written script, a grammar and inscriptions and all kinds of literature.

The long history of Sinhala civilisation is unique in the world. Other civilisations lasted comparatively a much shorter span such as Greek, Roman, Mayan and Harappan.

Where Indian history was concerned it was not seen as one country as we see it now; it was then so many territorial units with different monarchs. The difference between Sri Lanka and India during ancient times was that when Mughal invasions happened in Indian territories the religion and the culture totally changed. This did not happen in Sri Lanka.

The Sri Lankan Tamils were part of the ancient civilisation of this nation. The Muslims mainly came here as traders. They were peaceful, married Sinhalese women and adapted to the Sinhala customs. Their attire and diet got localised and they were never disloyal to the country they settled in.

The principal of cohesiveness and the fact that the word hela encompassed all those who arrived to and made this nation a home, far exceeds what we think of today as the ideal Western tolerance of other cultures. Colonisation and the complex social changes it bought changed our history and narrative of the Sinhala civilisation.

There are today misconceptions that are used to suit diverse international machinations. It is time we rectify this and use our heritage for the good of all and for the unity of the nation with a clear vision for national identity where all communities are respected.

Q: How can the Sinhala civilisation be upheld today for the purpose of bringing Sri Lankan communities together?

A. Traditional knowledge of all ethnicities of Sri Lanka should be respected, understood and promoted. If this was done connected to agriculture, soil preservation and concepts of wellbeing according to the traditional knowledge of our different districts we would have a more stable economy and avoid needless food imports.

If we preserved our crafts and arts as forms of strong export economy we would have a craft entrepreneurship based niche in the world. There is complex knowledge that we had connected to our natural resources. These could be arts and crafts of the Sinhala or Tamil or Muslim tradition rooted to Sri Lanka. A strong policy for national unity based on these concepts could be created provided there are people committed to it but much of our traditional knowledge is lost and this is the key challenge.

Patriotism and nationalism is not communalism. There is Jathikawadi and Jathikabedawadi. We must understand the difference. As reiterated before, the Sinhalese, as we can see from the many acts of ancient Sinhala kings, were a race which was accommodative of those of other beliefs and traditions. The Sinhalese were a humane race. They were not a race that propagated violence though their ancient armies were known to be powerful.

That is why in all of the long history of the Sinhalese you only hear of one war major ethnic based war – against Chola invader Elara. Here the justification for war was his identity as an invader, not as a Sri Lankan Tamil. It is this that has been misconstrued over time which we have to correct and pay serious attention to.

Before Elara there were two Chola horse merchants Sena and Guttika who sat on the throne in Anuradhapura. Dutugemunu united the country. Anuradhapura and Polonnaruwa were run by Cholas. Kalinga Magha from South India was the most destructive, burning all the ola leaf manuscripts and destroying places of worship.

Around the 12th and 13th century while a lot of invasions happened, Ruhuna remained independent and from there Sinhala kings came and conquered the Cholas from time to time. Vijayabahu the 1st conquered the Cholas and took over the country. The important thing is that the heart of the country remained the same. In India Maharajas became overrun by Sultans and the religion/cultural identity/architecture changed in the kingdom. Here it did not.

But a key aspect of our Buddhist civilisation is freedom. Ancient Lankan kings had granted the freedom to any foreigner settling in the country to follow his own religious path and this never affected the identity of the country. Yet, we today look at Western liberalism as the ideal of freedom. It is important that we re-connect to who were and are and we need clear thinking to be able to do this. Young people in universities should be encouraged to stay on in Sri Lanka and dedicate themselves to tasks such as these. We need to promote the authentic ethnics of connected with the Sinhala civilisation.

Q: How do you think Buddhism can be used for unity?

A. Buddhism is by itself a unifying concept.

Mettha, Karuna, Muditha, Upeksha should be practised to promote peace and social harmony. This is a very important aspect that should be remembered.

Buddhism should not be looked at as a religion but as a philosophy and a mind-based science for the good of all mankind. Irrespective of any religion everyone within the country should be encouraged to study this philosophy and science. Buddhism could also be described as a philosophy of nature. I think every Lankan should study Buddhism on these grounds.

Also, Buddhists should be encouraged to study other religions. Buddhism tolerates and questions. Therefore, it will be important for all Buddhists in this current age, to study other religions for the purpose of upholding peace and unity in the country. In the school curricula this should be incorporated. I have proposed this to the committee that is looking at education reforms in Sri Lanka. This would be a key factor to creating our own national unity model.

Anything that will enrich the mind of a child up to adulthood to be kind and compassionate should be incorporated aligned with anything that makes a child question. Questioning and acceptance go hand in hand for a Buddhist and this should be the case for the nation.

Q: Do you believe that a Sinhala Buddhist nation could be one which will unite and connect people and respect the Hindu culture within our island?

A. Definitely. Without a doubt. The term Sinhala Buddhist was never one which spelt out oppression as some people assume. We must clear our understanding on this and set forth an independent analysis on using the Buddhist identity for national unity, wellbeing and happiness for all.

NOTE: The above interview is part of a series promoting a Sri Lankan model of national unity, peace building and national prosperity based on traditional knowledge and intangible cultural heritage.