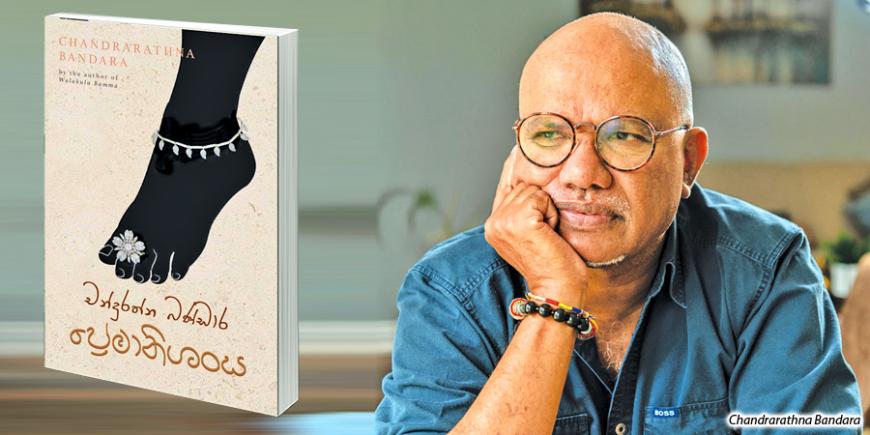

Premaanishansa: Fiction novel, 2021, 420 pages

Author: Chandrarathna Bandara

Printed by Sarasavi Publishers

“History is constructed relative to contemporary. But, if the true history barges to the present discourse in its real form, the consequences would be akin to a dinosaur confronting an elephant.”

Premaanishansa

Page 32 (paraphrased).

Chandrarathna Bandara’s latest creation, ‘Premaanishansa’, came out recently. This fiction is staged at present-day Sri Lanka as a clash of love, politics, ideology, personality and many morecomponents between two archaeology disciples working under the tutelage of Professor Senaka Bandaranayake.

Although this tale is about the life-voyage of two young professionals Niru and Sayuru—undertaken together as well as individually—underneath the storyline this is also a historical struggle of their ancestors dating back to the 18thcentury.

Chandrarathna Bandara has been a creative writer since his maiden collection of poems called ‘The Dream of an Uncouth Man’ published in1982 with Kapila M. Gamage and Arjuna Krishnarathna (Krishna Vasu). The zenith of his literary career was winning the D. R. Wijewardene Memorial Award for the best novel in 1992 for ‘Wana Sapu Mala’. His previous novel ‘Walakulu Bamma’ was shortlisted for Suwarna Pusthaka award in 2015.

Cultural

The storyline begins with a description of a bronze Buddha statue that Niru and Sayuru very reverently display in their apartment. This pre-Abhayagiri Mahayana cultural symbol predicts the trajectory of their future voyages that the author intends to guide them and us through.

Niru is a descendant from the family of Sir Muthu Coomaraswami, 18th century Tamil aristocrat and an intellectual. Niru follows the footsteps of her grandfather Ananda Coomaraswami in her passion of exploring ancient art and architecture in Sri Lanka.

Niru is highly vocal with certain arrogance, probably inherited from her larger-than-life great grandfather Muthu Coomaraswamy.

At the same time her social and political outlooks, especially her sexuality, are quite liberal and free spirited—conceivably more than our society finds acceptable. That was a trait her grandfather Ananda Coomaraswami showed, not only through his lifework of introducing Eastern art to the West but also being a resident of three countries (Sri Lanka, Great Britain, and United States). Perhaps his contemporaries in early 19th century may have found his four marriages as a sign of a free-spiritedness not in line with that era either.

Sayuru’s ancestors took a different route to prominence. His great grandfather Porolis Mudalali who was a devoted Christian, started as a labourer in graphite mines then made his wealth later as a liquor producer and a distributer. As most of such families did at that point in time his family converted to Buddhism and became patrons of Buddhist revival under Anagarika Dharmapala in late 18th century. By the time of Sayuru’s father, they had acquired sufficient wealth but not necessarily enough prestige. The main driving force behind their family history was to create a respectable lineage. Sayuru’s father is the main custodian of a temple in their ancestral village. He strongly demands that his son also assumes that heavy burden of bringing the family to higher prominence in the society as all their predecessors did.

The conflict between Niru and Sayuru’s relationship originates from the cultural mismatch between these two families. Niru plays the dominant role in their relationship while Sayuru struggles to define his part throughout the book. Niru sees the chains that his family has put on him in their century old struggle to add respectability to their immense wealth acquired through liquor trade. Only towards the end of the story he shows some independence and willingness, albeit reluctantly, to explore his own desires.

Chandrarathna Bandara, as an experienced writer with significant insights into our history, politics, and art, plays the role of a moderator in the struggle of this young couple in discovering their heritage as well as their inner selves. In that context Premanisansha is unique that is worth reading, then taking apart for a critical review. The author is not shy of demonstrating his language skills—sometimes even employing linguistic constrictor knots—while creating a masterpiece. The only reservation I have for his writing style is that more down to earth bookworms may find the language rather ‘heavy’ thereby restricting the audience to that school of art.

Chandrarathna has veered away from one of the underline themes of most of his work that are based on traditional village life guided by Buddhist heritage. In contrast, this time both protagonists are bourgeois elites who are quite at home at the Paradise Gallery Café discussing art and love while sharing a drink with Niru’s friend Kevin although Sayuru is slightly conflicted about Kevin’s sexual orientation unlike Niru who accepts Kevin for who he is. True to their yuppie thinking, the attempts of Sayuru’s father, Wilamulage, in promoting the temple that his family built are viewed with contempt by both as an out-of-date exercise.

But is it so? Is that the whole truth?

Self-interest notwithstanding, the role played by the new-rich class (although they may have acquired their wealth by liquor trade) during the Buddhist revival in late 1800s had an immensely positive contribution to our country.The same may or may not be true for the mini-revival that occurred in 1990s promoted by the new-rich class arrived after the free-market economy in 1977. Obviously, it is premature to judge the wave of the Buddhist revival embarked on by Sri Lankan expatriates in many metropolitans all over the western world these days.

Chandrarathna may have lost an opportunity to explore deeper into Wilamulage’s character. There must be a depth to his life than the two-dimensional caricature offered in the novel. On the other hand, Sayuru’s mother has more to her persona than depicted in the first half of the book. Her true feelings and inner strength are displayed when an enormous trauma is fallen on their lives.

Mainly academic

The author has also instilled in these characters, who appears to be subscribers of “woke generation” in the West, a deep appreciation of the cultures—both Sinhalese and Tamil—although at times readers may feel that part of the narration is mainly academic.

There is a significance of this intervention by the author since the theme of this novel is the battle between conservative society versus liberal decentres. Without deep insights into the culture that gave birth to a conservative society such as ours, the actions and words of the liberal elites may become counterproductive despite good intentions. This is valid not only for Sri Lanka but also other conservative societies such as the USA that value religious traditions where the pressures of the “woke culture” in fact are driving the country to more conservative political and social positions.

In the second half of the tale their relationship is seriously stress tested due to the mismatch of the dogmas guiding their families. Niru undertakes a pilgrimage to Kedarnath, Dharamshala and Lhasa in search of solace in response to this conflict.

Sayuru follows her when all contacts are lost after a flood in the Kedarnath Temple. His journey is less pilgrimage and more exploration to rediscover him. A new love-interest, Sofia, is introduced to him during that journey. That allows him to realise his inner desires as well as to widen his perspectives on love and life.

As the story is ending Niru shows a vulnerability for the first time in the book. There is no other way to describe the last chapter but as simply sad.The very end also feels abrupt with Sayuru expressing ambiguous feelings about Niru and Sofia.The part where a Tibetan death ritual is played at the Sky Burial cemetery in Lhasa—however noble is such a custom as an ultimate gift to the world by the dead—may leave the reader with a lingering melancholy.

Yet, I think, that the end chapter is the beginning when the reader falls in love with Niru.