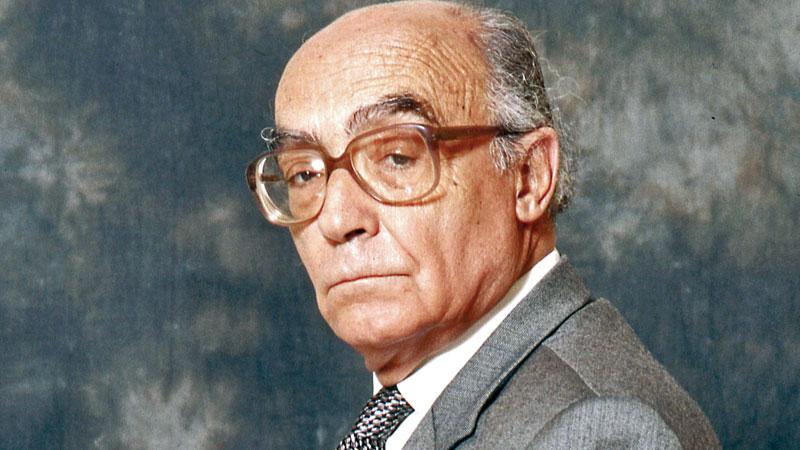

Portuguese author José Saramago, born on November 16, 1922, was awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1998, and he is the first Portuguese to win the award. He has been credited with 12 novels, and one of the most important among them is ‘Memorial do convento’ (1982; ‘Memoirs of the Convent’) which is translated into English as ‘Baltasar and Blimunda’. Saramago also wrote poetry, plays, several volumes of essays, short stories, autobiographical works, and translated books into Portuguese. His memoir ‘As pequenas memórias’ (2006; Small Memories) focuses on his childhood.

It is also noteworthy to mention that Saramago was a member of the Portuguese Communist Party. It is not surprising because he came from a very low social stratum - his parents were rural labourers, and grew up in great poverty in Lisbon. Starting his literary journey as a journalist and a translator, Saramago embarked on writing fiction after losing his job resulting from an anticommunist backlash.

It is also noteworthy to mention that Saramago was a member of the Portuguese Communist Party. It is not surprising because he came from a very low social stratum - his parents were rural labourers, and grew up in great poverty in Lisbon. Starting his literary journey as a journalist and a translator, Saramago embarked on writing fiction after losing his job resulting from an anticommunist backlash.

However, it was in his 50s that he began writing novels. His art of fiction, especially, is described in a Paris Review interview, so here we excerpt that interview to show Saramago’s art of fiction. The interview was done by Donzelina Barroso, and it took place on a sunny afternoon in March of 1997, at his home in Lanzarote.

Job

For me, writing is a job. I do not separate the work from the act of writing like two things that have nothing to do with each other. I arrange words one after another, or one in front of another, to tell a story, to say something that I consider important or useful, or at least important or useful to me. It is nothing more than this. I consider this my job.

Writes every day

When I am occupied with a work that requires continuity, a novel, for example, I write every day. Of course, I am subjected to all kinds of interruptions at home and interruptions due to traveling, but other than that, I am very regular. I am very disciplined. I do not force myself to work a certain number of hours per day, but I do require a certain amount of written work per day, which usually corresponds to two pages.

This morning I wrote two pages of a new novel, and tomorrow I shall write another two. You might think two pages per day is not very much, but there are other things I must do—writing other texts, responding to letters; on the other hand, two pages per day adds up to almost eight hundred per year.

No dramatics

In the end, I am quite normal. I don’t have odd habits. I don’t dramatize. Above all, I do not romanticize the act of writing. I don’t talk about the anguish I suffer in creating. I do not have a fear of the blank page, writer’s block, all those things that we hear about writers. I don’t have any of those problems, but I do have problems just like any other person doing any other type of work. Sometimes things do not come out as I want them to, or they don’t come out at all. When things do not come out as well as I would have liked, I have to resign myself to accepting them as they are.

“I use the computer as a typewriter”

(Now I compose) directly on a computer. The last book I wrote on a classic typewriter was ‘The History of the Siege of Lisbon’. The truth is, I had no difficulty in adapting to the keyboard at all. Contrary to what is often said about the computer compromising one’s style, I don’t think it compromises anything, and much less if it is used as I use it — like a typewriter.

What I do on the computer is exactly what I would do on the typewriter if I still had it, the only difference being that it is cleaner, more comfortable, and faster. Everything is better. The computer has no ill effects on my writing. That would be like saying that switching from writing by hand to writing on a typewriter would also cause a change in style. I don’t believe that to be the case. If a person has his own style, his own vocabulary, how can working on a computer come to alter those things?

However, I do continue to have a strong connection — and it is natural that I should — to paper, to the printed page. I always print each page that I finish. Without the printed page there I feel . . .

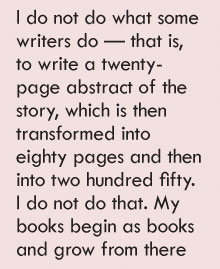

“Ninety percent of my work is in the first draft”

Once I have reached the end of a work, I reread the whole text. Normally at that point there are some alterations—small changes relating to specific details or style, or changes to make the text more exact—but never major ones. About ninety percent of my work is in the first writing I put down, and that stays as is.

I do not do what some writers do — that is, to write a twenty-page abstract of the story, which is then transformed into eighty pages and then into two hundred fifty. I do not do that. My books begin as books and grow from there. Right now I have one hundred thirty-two pages of a new novel, which I will not attempt to turn into one hundred eighty pages: they are what they are. There may be changes within these pages, but not the kind of changes that would be needed if I were working on a first draft of something that would eventually take on another form, either in length or in content. The alterations made are those needed for improvement, nothing more.

No rigid plan

I have a clear idea about where I want to go and where I need to go to reach that point. But it is never a rigid plan. In the end, I want to say what I want to say, but there is flexibility within that objective. I often use this analogy to explain what I mean: I know I want to travel from Lisbon to Porto, but I don’t know if the trip will be a straight line.

I have a clear idea about where I want to go and where I need to go to reach that point. But it is never a rigid plan. In the end, I want to say what I want to say, but there is flexibility within that objective. I often use this analogy to explain what I mean: I know I want to travel from Lisbon to Porto, but I don’t know if the trip will be a straight line.

I could even pass through Castelo Branco, which seems ridiculous because Castelo Branco is in the interior of the country—almost at the Spanish border—and Lisbon and Porto are both on the Atlantic coast.

What I mean is that the line by which I travel from one place to the next is always sinuous because it must accompany the development of the narrative, which might require something here or there that was not needed previously. The narrative must be attentive to the needs of a particular moment, which is to say that nothing is predetermined.

If a story were predetermined — even if that were possible, down to the last detail that is to be written—then the work would be a total failure. The book would be obliged to exist before it existed. A book comes into existence.

If I were to force a book to exist before it has come into being, then I would be doing something that is in opposition to the very nature of the development of the story that is being told.

I think this way of writing has permitted me — I am not sure what others would say — to create works that have solid structures. In my books each moment that passes takes into account what already has occurred.

Just as someone who builds has to balance one element against another in order to prevent the whole from collapsing, so too a book will develop — seeking out its own logic, not the structure that was predetermined for it.