After World War II, Brazil would get better in sports at the Olympic Games but it would mostly go unobserved for decades. The biggest impression came at the Helsinki 1952 Olympic Games. The Brazil’s sporting legend, Adhemar Ferreira da Silva who held the world record in the men’s triple jump won the gold with ease by almost 10 inches and set a new world record.

Da Silva would repeat as Olympic champion at Melbourne 1956 Olympics, proving himself to be one of the greats of triple jumping as his career would not only include two gold medals but he would also break the world record five times. Da Silva would prove to be an inspiring athlete as Brazil’s only Summer Olympic Games champion up until 1980.

Da Silva would repeat as Olympic champion at Melbourne 1956 Olympics, proving himself to be one of the greats of triple jumping as his career would not only include two gold medals but he would also break the world record five times. Da Silva would prove to be an inspiring athlete as Brazil’s only Summer Olympic Games champion up until 1980.

He was also the first Brazilian to hold a world record in any event and was among the greatest South American athletes in history.Though his speed and long jumping ability were not extraordinary, he became an exceptional triple jumper, especially noted for his balance. Later, Da Silva also got plaudits in another arena for his portrayal of Death in the award-winning 1959 Brazilian film ‘Orfeu Negro’ (Black Orpheus).

Birth and Growth

Adhemar Ferreira da Silva, the only son of a railway worker and a cook, born on September 29, 1927, had originally wanted to be a footballer but he switched to triple jump after trying it for the first time at the late age of 19. He was encouraged by the man who would become his lifelong coach, Dietrich Gerner. The German coach lived in Brazil and da Silva called him “my German dad”.

Within three months of taking up the sport, da Silva was breaking records, and within a year he was making his first appearance at the Olympic Games in London in 1948. In his early career he also competed in the long jump placed fourth at the 1951 Pan American Games in Buenos Aires.

At the 1952 Summer Olympics in Helsinki and the 1956 Summer Olympics in Melbourne, he became a two-time Olympic champion and world record holder and the only Brazilian athlete to have won gold medals in two consecutive Olympics until the London 2012 Summer Olympic games.

Da Silva’s exploits are forever marked by the presence of two gold stars on the badge of the Sao Paulo football club, the third most popular in Brazil, of which he was a member. The gold stars signify his world records in 1952 and 1955. He also competed for Club de Regattas Vasco da Gama from 1955 to 1959.

Professional Career and Olympic Games

Adhemar jumped 13.05 metres (42 feet 9.84 inches) in his first meet, in 1947.He soon showed his talent, breaking the national record and qualifying for the Brazilian team to 1948 Olympics, where he finished eighth in the triple jump.

In December 1950, he equaled the 14-year triple jump world record of 16.00 metres (52 feet 5.91 inches), set by Naoto Tajima at the 1936 Olympics and won triple jump jump gold at the 1951 Pan American Games before setting a world record of 16.01 at a national meet in Rio de Janeiro, in September 1951, which stamped him as the clear favorite at the 1952 Helsinki Olympics.

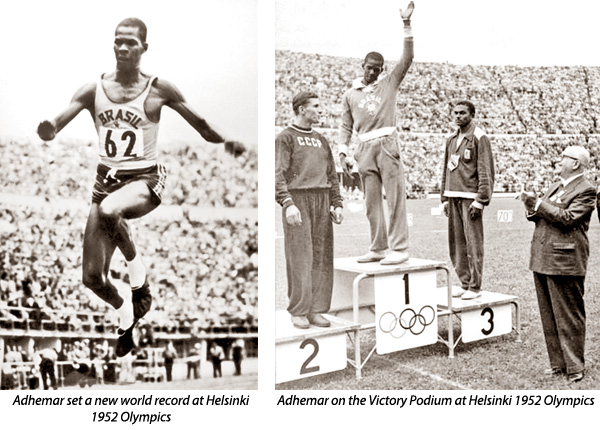

Despite other opponents with good medal credentials, da Silva was in a class of his own in the finals of Helsinki 1952 Olympics on July 23, 1952, leaping 15.95m with his opening jump. He won the gold medal comfortably, setting two world records in less than two hours in the final – 16.12 in round two and 16.22 in round five. In fact, he bettered the previous world record in Helsinki four times, posting 16.09 in round four and 16.05 in the final round.

It was remarkable because 16.00 metres had been jumped only three times before, twice by da Silva himself and once by Tajima. The world-renowned French athletics writer Alain Billouin described da Silva’s Helsinki performance with these words: “Gracefully, he skimmed through each hop-step-and-jump, displaying the poise and finesse of a samba dancer.”

In 1953, the Soviet Union’s triple jumper Leonid Shcherbakov set a world record that bested da Silva’s mark by 0.01 metre. Two years later, in his 100th competition, Ferreira da Silva erased Shcherbakov’s record with a mighty leap of 16.56-metre (54-foot 3.96 inch), the longest of his career at the 1955 Pan-American Games in Mexico City and went to the 1956 Olympics as the favorite.

At the 1956 Olympics in Melbourne, he won his second gold in the triple jump with an Olympic record of 16.35 in round four and had three other jumps over 16 metres.

Da Silva last won a medal at an international competition at the 1959 Pan American Games in Chicago, where he won his third Pan American triple jump title, and Da Silva made his final Olympic appearance in Rome in 1960, as Brazil’s flag-bearer at the opening ceremony.

The crowd shouted “Orfeu!” at him because of his role in the film, which was popular in Italy. At the age of 33, da Silva finished a disappointing 14th, unaware at the time that he was ill. He was given a standing ovation by the crowd when he departed, a fitting farewell to his athletics career.

Creation of “Victory Lap”

Da Silva created the “victory lap” after winning his first gold medal in Helsinki in 1952, where he became extraordinarily popular. He was on the front page of newspapers not just because he won but because, when he was asked questions in English, he answered in Finnish.

He even sang songs in Finnish. He had learned the language from a Finnish family living in his home city of Sao Paulo so he could better enjoy the Olympic experience, and to win the support of locals. “Most Finnish people had never seen a black man and here he was talking to them in Finnish, singing in Finnish,” said Adyel. “They couldn’t believe it. They loved him.”

A crowd of 70,000 chanted da Silva’s name during the contest, in which he broke the world record four times in six jumps. He was given a standing ovation at the medal presentation and a judge handed him a Brazil flag and told him: “The public wants you to take a walk.” He set off on the first victory lap in Olympic history, inventing the victory lap for Olympic champions.

In a 1991 interview da Silva recalled: “I did it with pleasure, because I wanted to thank those who had helped me to win the gold. And that was about it, from then on it began to be known as the victory lap. I still find it difficult to explain the emotion I felt that day.”

In 1993, da Silva was given another huge ovation in Helsinki when he was invited to an athletics meeting. “It was like I had never left,” he said. “Every Finn that I’ve ever met remembers me as the Hero of Helsinki.”

Rosemary Mula was a 15-year spectator at the time. There were no Australians in the final so the girls decided to cheer for da Silva, the elegant, cheerful champion.

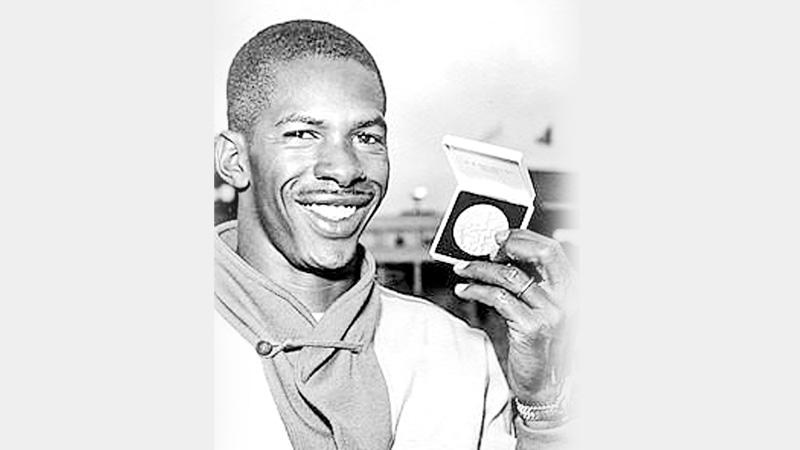

“Adhemar liked us, he could hear us cheering him, and he would come over and talk to us during the competition,” says Rosemary. “Later, after he had won, he said he had to go back and thank the kids who had been supporting him. His gold was in a box and he let me hold it. It was a magical moment.”

Later, when Rosemary became a dedicated Olympic volunteer, she met da Silva again. He became a close friend of Rosemary and her husband, Wilf, and stayed at their apartment during the Sydney 2000 Games. Wilf named one of his racehorses after da Silva.

After his death,Wilf and Rosemary Mulaset up a scholarship that pays for an exchange between Australian and Brazilian schools.

None of this was enough, to impress the organizers of the Rio 2016 Olympic Games in his home country. According to Rosemary Mula, “His family was neither invited to the opening ceremony, nor a single session of athletics or any other sport. A presence for the da Silva family at the triple jump final would surely have gone down well with the crowd.”

Film and Academic Degrees

In 1959, da Silva had an acting role at a musical film ‘Orfeu Negro’ based on a play ‘Orfeu da Conceiçao’ by Vinicius de Moraes, portraying Death, which won the Golden Palm of the Cannes Film Festival and an Academy Award for Best Foreign Language Film. The film is an adaptation of the Greek legend of Orpheus and Eurydice, set in the modern context of a Favela in Rio de Janeiro during Carnival.

Da Silva was studying for a physical education degree while he had his stint as an actor. “He was chosen because of his athletic body,” said Adyel. “Being an actor wasn’t his dream, and he didn’t do any more movies after that.” He did, though, maintain his impressive physique throughout his life.

Obama’s anthropologist mother, Ann Dunham, said ‘Orfeu Negro’ was her favourite film. This led the US President, who felt the black characters were depicted as “childlike”, to question his and her differing perceptions about race, as he revealed in his 1995 memoirs Dreams From My Father.

Instead of acting, da Silva worked in the 1950s as a civil servant for the Sao Paulo State Government, and kept studying and training. “I would work in the morning and afternoon, train at lunchtime, or at the end of the working day, and study at night,” he said in a 1993 interview.

Besides physical education, he had degrees in law, the arts and, having gone back to studying at the age of 60, public relations. He learned English, Finnish, French, Italian, Spanish, German and Japanese. He played guitar and sang. He was a newspaper columnist, a television commentator on athletics, and he worked for the diplomatic service as Brazil’s cultural attache in Lagos, Nigeria from 1964 to 1967.

Adhemar Ferreira da Silva graduated as a sculptor from the Federal Institute of Sao Paulo in 1948, received a physical education degree from the Preparatory School of Cadets of the Brazilian Army, law degree from the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro in 1968, and a public relations degree in 1990 from the Faculdade Casper Libero, a private university in Sao Paulo.

“He was always a very curious man, always wanting to learn,” said Adyel. “He was always positive, and the only time I saw him really brought low was when my brother (Adhemar Junior) died in a motorbike accident. He was 32.”

The ‘Jump for Life’ Project

The ‘Jump for Life’ project aims to introduce people from deprived areas to athletics. His home city is the base for the ‘Jump for Life’ Institute set up by his family to provide opportunities in sport to disadvantaged children.

The Institute, sponsored by a bank, reached out to one school when it started three years ago and now has a presence in 17 schools. “The next project is to teach physical education teachers how to coach the kids,” said Adyel, Adhemar da Silva’s daughter and President of the ‘Jump for Life.’

She and her fellow workers at the Institute are doing exactly what da Silva tried to do for much of his life - taking athletics to children to give them a sporting chance.

Their current focus is on a region of high deprivation, Vale do Ribeira. “You can find great athletes there, but they know nothing about track and field,” said Adyel.

Adyel’s son Diego married Rosemar Coelho Neto Menasse, who is an inspiration to the children they work with.

She is from Vale do Ribeira and became an Olympic sprinter who stands to win a medal. She was in the Brazil team that finished fourth in the 2008 final.

“It’s beautiful to see the small children listening to her, enraptured,” said Adyel. “She is quite a celebrity to them because she is one of them. People in Brazil don’t realize how important sport is as a social tool. My father was always aware of that.

“We want to hire coaches to coach the teachers so they can bring those children through in track and field. Our Institute is not big, nor is our budget. We are not setting out to search for Olympic gold medalists, we’re looking for children who, through athletics, can make a jump in their own life, to find something they want to do and do their best.”“There is so much athletic talent here in Brazil. Let’s find the best, let’s want the best.”

Legacy

When the French director Marcel Camus took the classic Greek tale of Orpheus and Eurydice to a Brazilian Favela in the late 1950s, he created a film that would not only beguile Barack Obama and his mother, but would make a little bit of Olympic history.

The multi-talented triple jumper Adhemar da Silva, who was cast as Death in Camus’s ‘Orfeu Negro’ is perhaps the only or among a very few Olympic athletics gold medalists to have had a major role in a movie that won the Cannes prize in 1959, and the other awards in 1960, the year of the Rome Olympics.

The Brazil’s foremost Olympian, South America’s greatest athlete, and one of the most popular and charismatic figures in his nation’s sporting history, bid farewell to the Summer Olympic Games with his fourth and final appearance in Rome 1960.

Later in life da Silva became a “guru” for Brazilian sports administrators. “The first thing I did when I was appointed was call Adhemar and Pele for a talk,” said Carlos Melles after he was made Brazil’s Sports Minister in 2000. “Adhemar was my number one helper.”

He left quite a legacy, when he died in 2001, his casket was carried on a six-mile funeral procession preceded by athletes in their running attire. He is still the only South American to have won two Olympic athletics gold medals. He set up programs for deprived children in his belief that, “sport, especially among the poor, is the only and best way for social advancement, and for escaping violence and drugs.”

His name lives on in annual awards, in a Brazil-Australia exchange program for young athletes and at the ‘Jump for Life’ institute in Sao Paulo. The legendary Adhemar da Silva is among the inaugural 12 athletes inducted into the IAAF Hall of Fame in 2012.

(The author is the winner of Presidential Awards for Sports and recipient of multiple National Accolades for Academic pursuits. He possesses a PhD, MPhil and double MSc. He can be reached at [email protected])