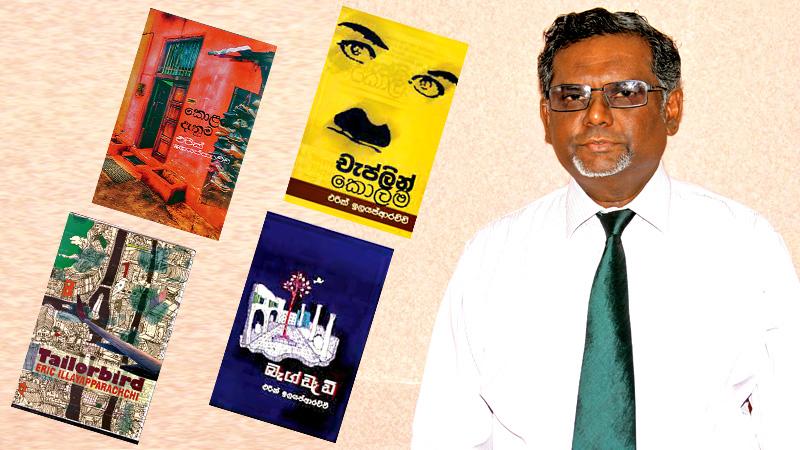

The State Literary Awards festival for 2021 was held at the BMICH last week. There, the prize for the best Sinhala novel in 2020 was awarded to ‘Messa’ (Fly) by Eric Illayapparachchi, a veteran writer, poet and a critic. ‘Messa’ is published by Godage Book Publishers. The Past year’s Swarna Pustaka award also went to a novel by Illayapparachchi which is ‘Petha’. Illayapparachchi is a prolific writer who produced more than 50 books. As he is a writer of number of literary prizes, and a critic of great insights, the Sunday Observer spoke to him to discuss literary awards and current issues of literary assessing in Sri Lanka.

Excerpts:

Q:You have won many literary awards. Do you think awards are helpful for a writer?

A: I feel that it encourages writing, but one should not depend on literary prizes, because the best literature was born in an environment where there were no prizes. A prize means a close reading by some group of literary taste which is good for a writer. And the jury is, itself, judged by their judgments as well - this affects both the writer and jury. On the other hand, there are some great writers in world literature who never won the Nobel Prize. For instance, James Joyce, Jorge Luis Borges, Graham Green never won the Nobel Prize for literature, though they are the most deserved.

The paramount thing in literary awards is to focus the reader’s attention on the works of obscure writers and obscure works of known writers. For instance, until this years’ Nobel Prize people had very little knowledge about Abdulrazak Gurnah, the Tanzanian – British writer. And due to the plethora of publishing houses and publications, it is very difficult for the readers to focus on every book that is published, hence, the importance of awards.

And in the Sri Lankan context, we often see books are being propagated in social media. But there are people who do not use social media, particularly writers from the older generation who never associate with social media. Thereby, they have no chance to read those books on social media. I remember a recent Sinhala translation (Mataka Miyedena Sanda) of an English novel (‘When Memory Dies’) authored by Ambalawanan Sivanandan, a Jaffna writer. Though this is a central book on Tamil society and the arly Leftist movement in Sri Lanka, most people were not aware of it. Hence, prizes are helpful for readers and writers to find good books.

Q:Yet, being a literary award winning work is no guarantee of literary merit?

A: Yes, that happens when we do not have powerful literary criteria. Our criteria on books are always changing. If one criterion is accepted in one time, the next time it would absent. Certain standards that was used in particular time to judge the literary merit of a work, is not necessarily utilised the next time when work is to be judged. Hence, there is no continuity in it.

When speaking in terms of painting, recently an American writer named Michael Basquiat entered the mainstream art. Basquiat is not a member of the elite. He is a graffiti artist, mainly painted on walls. He even didn’t wear tie and coats. He is, in fact, a punk, a hip-pop musician type man. But, in America, his stature was elevated to that of a great classical artist and his paintings were sold at a prize of Picasso’s paintings. How did that happen? It is because they had very powerful artistic criteria to assess art. We lack this thing. The massive disadvantage of this is that inability to identify new talents.

Q:Do you mean that we don’t have qualified persons of eminence to judge the merits of a literary work?

A: Definitely, the criteria to assess literature depend on the judges who had been selected. In the above mentioned example, American critics could introduce Michael Basquiat as a classical artist, because they knew the tradition as well as modernism. The issues in our literary judgments arise just because of our ignorance of relationship between tradition and modernism.

T.S. Eliot says that every good book defines order of our poets. In other words, hierarchy of our known poets changes with every new (high) book. Thus, the newly introduced writer also becomes a person who joins the tradition and then makes changes in the tradition. However, the mere fact of novelty is not a guarantee of merit - we cannot appreciate an art work because of its newness.

In terms of Sinhala literature, the crisis has arisen mainly due to the myths that were introduced to realism by critics. There are two things. First, there are the injuries that propagandist writers cause to realistic literature. Second, the misunderstanding generated by magical realism. It is not a problem in magical realism. The problem lies in its introduction to Sinhala literature. Our Sinhala writers distort the meaning of magical realism when introducing it. Magical realism is, in fact, a part of realism. It is not a separate element. For instance, Franz Kafka is a realist, he is not a magical realist as we express - he used realism in his own way which you cannot say magical or any other style.

This misunderstanding stops if we have critical analysis of magical realism. We know that we have enough new literature through translations, but we don’t have new criticism of the new literature. They have not reached us through translations. Therefore, though we discuss one or two fictions of magical realism. For instance, ‘One Hundred Years of Solitude’ by Gabriel Garcia Marquez, critical works of them – books on how Western critics saw the novel – never reached us.

Now, Western critics see the Marquez’ novel in a completely different way. They say that though this book sporadically bears magical elements, it is, in fact, a family story. This review is by Fredrick Jameson. There he says, “There is no magic; no metaphor, it’s a family story.” He says that you cannot find family stories in American or English literature, because there is no family in those countries. Family is only in Latin American countries, thereby they can write about it.

In this sense, ‘One Hundred Years of Solitude’ by Gabriel Garcia Marquez is abused in Sri Lanka. Sinhala critics and writers misuse the book to attack the realistic literature in Sinhala.

Q: Once, in an interview with a journalist, Marquez said he didn’t write anything which could not be seen in his society.

A: Of course. As I said earlier Kafka is also misused in our country. He is the most modern realist, but when introducing him we distort his picture. For instance, take ‘Metamorphosis ‘ by him. It is, actually, about tragedy of a worker, tragedy of the relationship between man and work, the sustenance of family depends on the employer paying the wages. Kafka brings this reality, not any other magical reality.

Another misuse in Sri Lanka is that our perception on content and form. We still consider that content and form are two things, but it is completely wrong. Content and form are one, not two. There is no new form or structure for a writer when writing fiction. He only writes in the form that his content takes. In this way, taking content and form separately is a total myth spread by propagandist writers in Sri Lanka.

We know the shape of an aeroplane. It needs its shape to fly, with a train-shape it can’t fly. Hence, shape of the aeroplane is a part of a plane. There are no two things in it. However, the thing that happened in Sinhala literature was a search for new forms at the expense of content. This is why books entirely focused on form came out as fiction.

Q: Our literary judges seem to have cultural or political taste instead of literary taste which is why they keep Kafka or Marquez at a cultural or political ground.

A: It is a problem of our culture politics. Look at Europe’s great thinkers. They are radical in their philosophical discourse, but they also indulge in a deep literary reading. But we try to admire very low cinema or art to showcase our radicalism. This does not happen in Europe, because they have mainstream art tradition. They cannot go against it to admire such low art.

Q: The final result of our ill-literary reading is highlighting the utter nonsense as literary works, which subsequently affects both the reader and writer?

A: The most disastrous thing that happens in our culture political book assessment is loss of literature to the country owing to the inability to identify literature. This is, I think, a conspiracy, because it is a conscious effort to deprive literature from people. Not only do they deprive literature, they also replace it with non art such as advertising, business, media and so on. But take the Dadaism in Europe.

It came as an anti-art movement between two world wars. The objective of it was having fun of social and artistic conventions. For instance, they gave a moustache to Monaliza when reproducing it. Though this was funny, it also gave an artistic meaning to it. Whatever it did in Dadaism ultimately became artistic. But in our art or literature it is different. It never takes art when we do these types of funny things for an art work. In fact, our experiments in art accounts for distorting the art work which is the difference between our art and Dadaistic art.

Q: When talking about literary awards we also have to discuss alternative literary festivals. In the early 90s, we saw such festivals as independent literary festivals in Colombo organised by Vibhavi. Recently, we saw a web literary festival as an example for this. How do you see these festivals and an alternative literary stream?

A: I think literature belongs to mainstream, not to alternative. A writer’s struggle lies in the mainstream, not in the alternative. A critic’s struggle also lies in that path. There might be disagreements in the mainstream, because it is also a place where some ideologies are collected. But instead of struggling within it, moving away from it and then starting an alternative is completely a wrong path as there wasn’t a literature called alternative literature.

Now we are talking about modern art. But if you read more about it, you will find that modern art originated not as an alternative, but as an art confronting the classical art where modern artists confronted the academic art. We see there is an ideology in mainstream art, but alternative art also has an ideology. It is an art which is basically originated in an ideology. Mainstream art never originated in an ideology. Ideology came into it after it was developed. This is the problem in alternative literature, because with ideological origin it has no existence as an art.

If you see the alternative literary festivals you will often see that only the ideological books are being awarded with prizes. It is not surprising, because the panel of judges seek only the ideologies in literary works.

Q: You mean there isn’t any literary value in those award winning books?

A: Definitely. Here you mention the word literary value. I think it is a very important thing. Literature is not an ideology. Literature exists in a work, it is a practice or usage.

Q: How about the novel ‘Outsider’ by Albert Camu where there is an ideology which is existentialism?

A: Of course, there is an ideology in that book, but it wasn’t written for defining the ideology. Ideology of ‘Outsider’ is an intrinsic part of the novel. You cannot separate its ideology from the novel. The two are one in the novel. If not, it will be propagandist literature.

Here, we have to see how the novels of great ideology such as ‘Outsider’, ‘Lady Chatterlly’s Lover’, ‘Notes from the Underground’ belonged to the tradition of great literature. If we look at ‘Outsider’ by Camu, its introduction is written by Jean Paul Sartre who was the greatest thinker and critic in France. Sartre was at the mainstream, not at the alternative. He was a university lecturer, a Marxist and an activist.

Thus, ‘Outsider’ was run at the mainstream. Even Dostoevsky and Chekov also struggled at the mainstream literary tradition. For some writers, there might have some delay for entering the mainstream, but if one moves into alternative literature his/her works do not enter the mainstream. Alternative is not the delay. It exists forever in a place where there is no literature.

I think the challenge for a writer or an artist is to overcome the lateness or struggle against the lateness. Take Japanese novelists who emerged after the Second World War such as Ukio Mishima and Yasunari Kawabata. After they entered the mainstream they were highly welcome by the reading public. But Martin Wickramasinghe couldn’t accept them as good novelists, he looked down upon them. This is the difference between them and us. ‘Dr. Shivago’ is also a book similar to that. Although it was received by Europe we were late to welcome it.

Q: Can we consider alternative literature as non literature?

A: Of course. If a book is an alternative literary work, it wouldn’t be at alternative place forever. One way or another it enters the mainstream. But if a book exists forever at the alternative, it means it is non art or non literature. We know about the Booker Prize. But have you ever heard that it was awarded to an alternative literary work? Never. Though it consists of a number of literary experiments, it never goes to an alternative literary book. Always the prize was awarded to realistic novel.

You said about non literature. In my view, magical realistic trend in Sri Lanka is a total anti-art movement, it is non literature. This movement deprives the literature for the public. If they are deprived of literature, it is very easy to give them rubbish as art. So, it is a business strategy. The real motive behind the magical realism trend in Sri Lanka is to turn reader into customer or consumer.

Q: During the past few weeks we saw many international literary award ceremonies such as The Nobel Prize, The Booker Prize, National Book Award and Neustadt International Prize. The common characteristic of these awards is that their literary panels are consisted of literary people. But in our literary festivals the panels are included with people from other fields as well.

A: You raise a very good point. If we assign the task of literary assessing to film makers, film stars, dramatists, song writers or painters, the assessing task altogether collapses which is what we witness mostly. The reason why is that they have no literary mindset or literary imaginary world. For instance, a film maker reads a fiction in pictures or images. Images and editing automatically come into his assessment when he reads a book. Even the high film maker cannot grasp the literary work correctly. This is why we never heard that Satyajit Ray or Akira Kurasawa were at literary panels though they were high cinematographers and a script writers. On the other hand, writers are unsuccessful in assessing movies, music and paintings.

Literature should be assessed by literary minds. Other artists are absent of this mindset. They have completely different mental framework as against the writers. This is important. Just observe the life styles of these people. For instance, a filmmaker has the life style of running, shouting and busying in physical acts. But a writer is introverted. He cannot write a novel while travelling on a bus though a filmmaker can operate the camera from a bus. This is why good film makers went in search of literature by their film works.

Satyajit Ray did this through his movies. Most of his movies are based on Bengali novels including highly acclaimed ‘Pather Panchali’. But if we assign him in literary assessing, that literature turns into a thing that follows cinema.

And literature is older than cinema, drama and others.

Their histories are different. In this backdrop, assigning a dramatist or filmmaker to assessing books raises many issues. It is more productive to assign a school teacher to judge literature.

Q: During the past few decades, we often saw song writers or lyricists came into assess books. Sometimes the whole literary assessment procedure were organised and operated by the lyricists. Do you think it is appropriate?

A: In Sri Lanka, a lyricist is a culprit. At first, he is a poet, but then because of the publicity and other petty rewards, he moves into song writing where there is no poetry. In this new field, he cannot engage in poetry writing as it is more serious for shallow fans, so they dilute or adulterate the poetry which is not acceptable in the literary point of view – hence he is a culprit. However, if a lyricist was assigned poetry assessing or poetry reviewing, the destruction of it is huge - it is the largest damage that one can do for art of poetry, because lyricist’s job is to adulterate things. I consider this as an invasion of literary values and destruction of literary establishments.