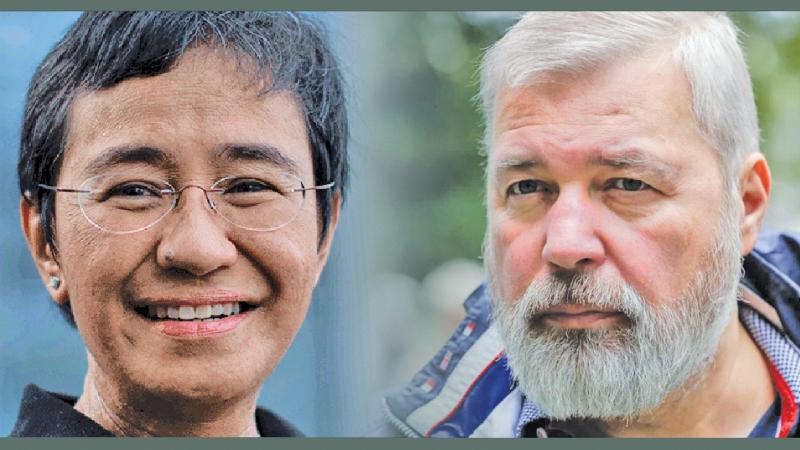

The Nobel Peace Prize for 2021 was awarded to two journalists from two countries: Maria Ressa from Philippines, and Dmitry A. Muratov from Russia. The official award ceremony was held at Oslo City Hall, Norway, on December 10, and the Nobel Committee praised the two journalists for “their efforts to safeguard freedom of expression, which is a precondition for democracy and lasting peace” and their “courageous fight for freedom of expression in the Philippines and Russia”.

This is the second time that journalists won the Nobel Peace Prize. The first was Carl von Ossietzky, a German journalist, in 1935. It was for his revelation on how Hitler was secretly rearming Germany - but afterwards, Ossietzky was detained in a Nazi concentration camp and later died.

The two winners of the Prize received two medals with the effigy of the prizes founder Alfred Nobel and a diploma, besides 10 million Swedish kronor ($1.1m) to be shared between them - they were chosen out of 329 candidates for the Prize. The speciality about this year’s Prize is that only its ceremony was held in Oslo, Norway, while the other ceremonies - Nobel Prize ceremonies for physics, chemistry, medicine, literature and economics - were held in the laureates’ hometowns due to the Covid-19 pandemic.

Facts about the winners

Filipina Journalist Maria Ressa, 58, is the chief executive and co-founder of the online news platform Rappler, founded in 2012. The Rappler news web, known for its intelligent analysis and hard-hitting investigations, has 4.5 million followers on Facebook. It is devoted to aggressive reporting on the administration of President Rodrigo Duterte, who cannot run again. Most of Rappler’s reporters are in their 20s, and have investigated Duterte’s extrajudicial campaign to kill people suspected of dealing or using drugs while documenting the spread of government disinformation on Facebook.

Filipina Journalist Maria Ressa, 58, is the chief executive and co-founder of the online news platform Rappler, founded in 2012. The Rappler news web, known for its intelligent analysis and hard-hitting investigations, has 4.5 million followers on Facebook. It is devoted to aggressive reporting on the administration of President Rodrigo Duterte, who cannot run again. Most of Rappler’s reporters are in their 20s, and have investigated Duterte’s extrajudicial campaign to kill people suspected of dealing or using drugs while documenting the spread of government disinformation on Facebook.

Ressa is praised for exposing abuses of power and growing authoritarianism under the Philippine President, Rodrigo Duterte, and because of this the Government has filed seven criminal charges against her, including for cyber libel and tax evasion. If she is convicted it could lead to about 100 years in jail. After an appeal by Ressa, she was granted permission to attend the Nobel Prize ceremony earlier this month by the Philippine Court of Appeals, which ruled she was not a flight risk. Before the Nobel announcement Ressa had been Time’s Person of the Year in 2018. Ressa, in fact, grew up in New Jersey and graduated from Princeton. She is also a Hauser Leader at the Centre for Public Leadership and a Joan Shorenstein Fellow at the Shorenstein Centre on Media, Politics and Public Policy.

Muratov, 59, who shared the 2021 Nobel Peace Prize, is the Editor-in-Chief of Novaya Gazeta which he co-founded in 1993. He is described as one of the most prominent defenders of freedom of speech in Russia today. Novaya Gazeta is one of the few remaining newspapers in Russia to be highly critical of the ruling elite, particularly President Vladimir Putin. Published three times a week, it regularly runs investigations into alleged corruption and other malpractice in ruling circles, and highlights the plight of people it considers victims of official abuse. The newspaper has been subjected to threats and harassment, including over its reporting of human rights abuses in Chechnya. Anna Politkovskaya is one of the six Novaya Gazeta journalists and contributors to have been killed in connection with their work since 2000. The Kremlin, which has frequently opposed the paper, congratulated Muratov for his Nobel Prize win.

Warning at the Acceptance Speeches

When receiving the award, Ressa and Muratov, praised the Nobel Committee for recognising the role of the journalists. “By giving this to journalists today, the Nobel Committee is signaling a similar historical moment, another existential point for democracy,” Ressa declared.

“We’re at a sliding-door moment, where we can continue down the path we’re on and descend further into fascism, or we can each choose to fight for a better world,” there she stated.

The two also used their acceptance speeches to express alarm about the threats to democracies and call for greater accountability for social media companies that Ressa said are dividing and radicalizing societies. In her speech, Ressa criticised social media companies still operated with impunity.

“Silicon Valley’s sins came home to roost in the United States on January 6 with mob violence on Capitol Hill… These American companies controlling our global information ecosystem are biased against facts, biased against journalists,” she said. “They are — by design — dividing us and radicalising us.”

She denounced U.S. social media companies, saying they promoted a “toxic sludge” of misinformation: “Our greatest need today is to transform that hate and violence, the toxic sludge that’s coursing through our information ecosystem, prioritized by American internet companies that make more money by spreading that hate and triggering the worst in us.”

Muratov, in his speech, made an impassioned plea against an escalation of violence, condemning the “militaristic rhetoric” prevalent in Russian state controlled media. His remarks were meant to serve as an urgent warning. But when he made his speech, Russia has massed nearly 100,000 troops across Ukraine’s borders, raising concerns of an invasion.

Muratov, in his speech, made an impassioned plea against an escalation of violence, condemning the “militaristic rhetoric” prevalent in Russian state controlled media. His remarks were meant to serve as an urgent warning. But when he made his speech, Russia has massed nearly 100,000 troops across Ukraine’s borders, raising concerns of an invasion.

“In the heads of some crazy geopoliticians, a war between Russia and Ukraine is not something impossible any longer,” he warned. “But I know that wars end with identifying soldiers and exchanging prisoners,” he said, referencing his newspaper’s role in identifying soldiers and exchanging prisoners during the Chechen war.

He also spoke about political repression and torture in contemporary Russia.

“We hear more and more often about torture of convicts and detainees,” he said. “People are being tortured to the breaking point, to make the prison sentence even more brutal. This is barbaric.”

He said he would present an initiative to set up “an international tribunal against torture, which will have the task to gather information on torture in different parts of the world and different countries, and to identify the executioners and the authorities involved in such crimes.”

At the same time, he said, the ideas of liberal democracy are under threat.

“The world has fallen out of love with democracy,” Muratov lamented. “The world has become disappointed with the elites in power. The world has begun to turn to dictatorship.”

He further reiterated: “The powerful actively promote the idea of war,” he said. “Aggressive marketing of war affects people and they start thinking that war is acceptable.”

Dedication of the Prize

Muratov has dedicated the prize to his six slain colleagues at Novaya Gazeta, including Anna Politkovskaya, whose 2006 murder in the elevator of her apartment block has never been solved. When the award was announced, he also said that opposition politician Aleksei A. Navalny, who was poisoned last year and has been in jail since January, deserved to have received it.

Muratov is the third Russian to win the Nobel Peace Prize, after the Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev and the physicist and dissident Andrei D. Sakharov, who won in 1975 for his human rights advocacy, while Ressa is the first Filipino to win it. In both laureates’ home countries, the climate for independent journalism is dire: ‘Reporters Without Borders’ in their 2020 global survey of press freedoms ranked the Philippines 138th out of 180 countries, and Russia was 150th. After Ressa arrived in Oslo to attend the Nobel ceremony, she heard the news that a former colleague, Jesus Yutrago Malabanan, a prominent Philippine reporter who had investigated Philippines’ President Duterte’s drug war, had been shot in the head and killed.

Ressa, in her remarks, said she spoke as a “representative of every journalist around the world who is forced to sacrifice so much to hold the line, to stay true to our values and mission: to bring you the truth and hold power to account.”