One of the greatest long-distance runners of the 20th century, Emil Zatopek, shot to great fame with his three mesmerizing victories with new Olympic records at the Summer Olympic Games of Helsinki 1952. He won his first gold in 10,000m on July 20 with 29:17.0, second gold in 5,000m on July 24 clocking 14:06.6 and his final gold at his debut marathon on July 27 with 2:23:03.2.

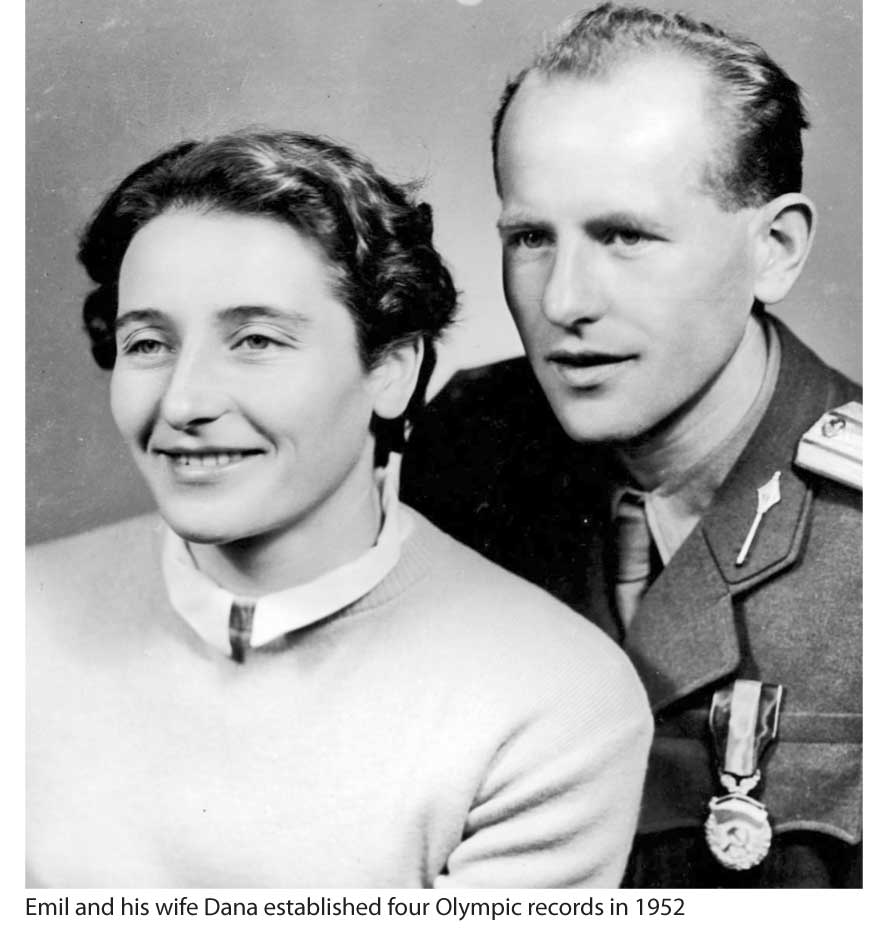

One athlete who had particular cause for joy at Emil’s feat was Dana Zatopkova, who happened to be his wife and winner of gold in javelin throw on July 24 with a new Olympic record of 50.47m. Emil and Dana, born on the same day in 1922, won Olympic gold medals on the same day in 1952. They became the first married couple to emerge Olympic champions in athletics.

Emil Zatopek is known for his hard-working nature and tough and challenging training methods. He is known to have pushed himself through grueling and strenuous training routines in order to get the best out of himself. The legendary runner was nicknamed ‘Czech Locomotive’ and ‘Bouncing Czech’ for his extraordinary abilities to perform consistently on the track. He set a total of 18 world records in 5000m, 10,000m, 10 miles, 20,000m, 15 miles, 25,000m and 30,000m.

Early Years of Emil

Emil Zatopek was born in Koprivnice, Czechoslovakia on September 19, 1922. He was the seventh child in a modest family. Aged 16, he started working at Bata, a shoe factory, in Zlin in 1937. Emil shared: “One day, the factory sports coach, who was very strict, pointed at four boys, including me, and ordered us to run in a race. I protested that I was weak and not fit to run, but the coach sent me for a physical examination, and the doctor said that I was perfectly well. So, I had to run, and when I got started, I felt I wanted to win. But I only came in second. That’s the way it started.”

Ever since, he began to take a serious interest in running. He joined the local athletic club, where he developed his own training program, modelled on the great Finnish Olympian Paavo Nurmi. In 1944, Emil broke the Czechoslovak records for 2,000m, 3,000m and 5,000m.

He joined the Czechoslovak Army at the end of the World War II and graduated from the Military Academy in Hranice in 1947. Meanwhile, he was chosen to run for the Czechoslovak national team in the European Championships in Oslo in 1946. He competed in 5000m and improved his own Czechoslovak record to 14:25.8.

London 1948 Olympics

In 1948, Emil participated in 10,000m in Budapest and was victorious, setting a new national record. Later, he made his Olympic debut at London 1948. He won his first Olympic gold in 10,000m and annexed a silver from 5000m. On October 22, 1949, Emil established a new world record in 10,000m with 29:21.2 at Ostrava, Czech Republic. Then, on August 4, 1950, he improved it to 29:02.6 in Turku, Finland. In 1950, he was the winner of 5000m and 10,000m at the European Championships. In 1951, he participated in IAAF’s ‘one hour run.’

Helsinki 1952 Olympics

At Helsinki 1952 Olympics, Emil won gold in 5000m, 10,000m, and the marathon, breaking Olympic records in each event. Emil is the only athlete to win the three long-distance events at the same games in the modern Olympic history. He opened his campaign in 10,000m, taking the lead from the start and then never relinquishing it. One by one, the main challengers fell off, unable to keep up with his relentless pace. Emil won the gold with a new Olympic record.

Apparently untroubled by tiredness, he then turned to 5000m, spending most of his heat, talking to the other runners and allowing several to finish ahead of him, with his qualification assured. However, when it came to the final, Emil’s focus and steely determination came to the fore. Emil led at the bell, but through the last lap he dropped back into fourth. He responded on the back bend, moving away from the curb and powering into the lead.

His victory came after a ferocious last lap in 57.5 secs. He crossed the line, setting another Olympic record. After two events Emil had claimed two golds and two records. Emil then decided at the last minute to compete in the marathon for the first time in his life.

It seemed like a mission impossible. He had never run the distance before and his exertions in 5000m and 10,000m would surely leave him too exhausted. But he was adamant he could do it. His only concern was that he was not familiar with the tactical nuances of running a marathon. His solution was to follow the British world record holder Jim Peters, who started at a ferocious pace.

After a punishing first 15 km, in which Peters overtaxed himself, Emil asked the Englishman what he thought of the race thus far. The astonished Peters told the Czech that the pace was “too slow,” in an attempt to slip up Emil, at which point Emil simply accelerated.

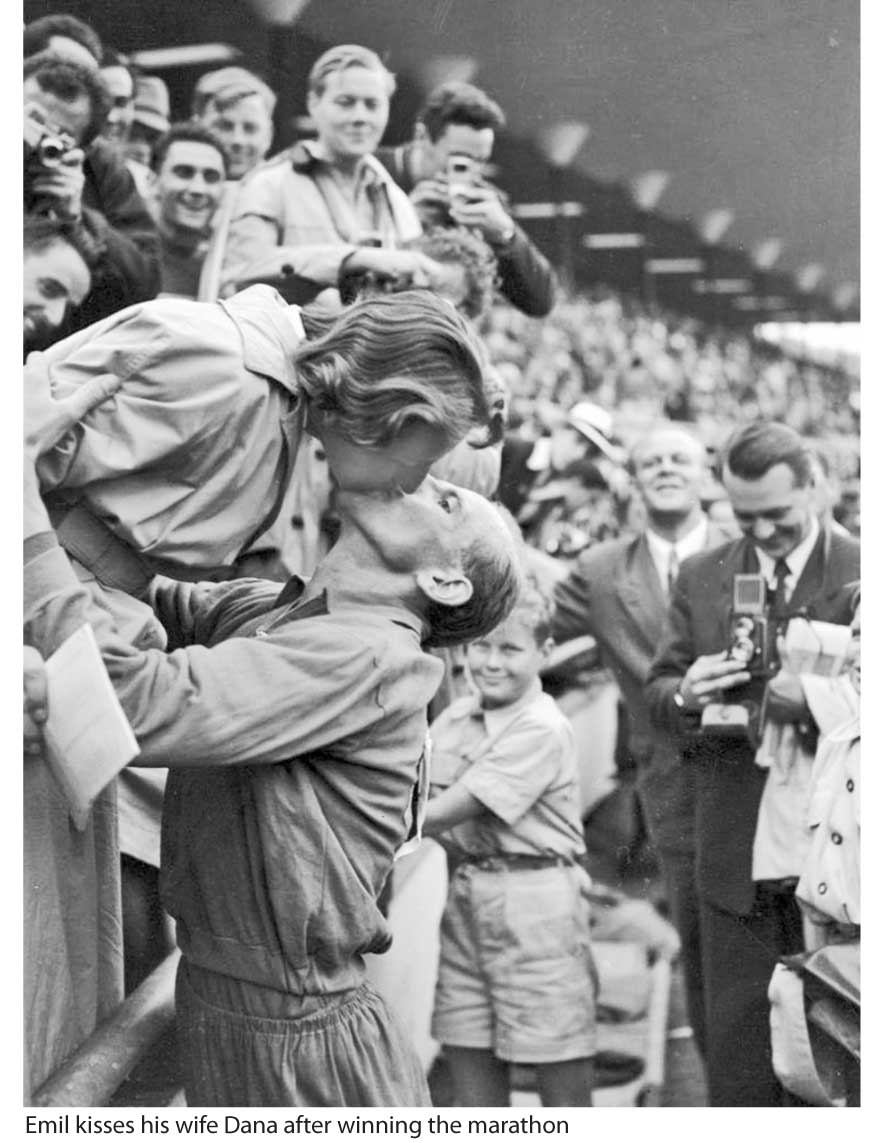

With six miles to go, Emil was at the front, and was now taking the time to chat to spectators and police officers along the course. The marathon debutant took gold by a stunning margin and set yet another Olympic record, delighting the crowd and earning him a lap of honor on the shoulders of the Jamaican sprint team.

With six miles to go, Emil was at the front, and was now taking the time to chat to spectators and police officers along the course. The marathon debutant took gold by a stunning margin and set yet another Olympic record, delighting the crowd and earning him a lap of honor on the shoulders of the Jamaican sprint team.

The whole world, it seemed, had come to adore the exploits of this well-mannered, gregarious and happy-go-lucky runner. Famously, the chants of “Za-to-Pek” that resounded around the Olympic stadium became something of a Helsinki 1952 anthem. The Olympic love and marriage of Emil and Dana enthralled the sporting world.

Melbourne 1956 Olympics

On November 1, 1953, Emil improved his 10,000m world record to 29:01.6 at Stara Boleslav, Czech Republic. On May 30, 1954, he established a new world record in 5000m, clocking 13:57.2 in Paris, France. Within two days on June 1, he improved his world record in 10,000m as well in Brussels, Belgium becoming the first to break 29-minute barrier, winning the gold at the European Athletics Championships. In 1956, after recovering from a groin injury, he participated in Melbourne 1956 Olympics, where he finished the marathon in the sixth position.

Marriage to Adorable Dana

Born on exactly the same day as her husband, Dana had excelled at a range of sports as a youngster, notably handball. She took up the javelin in her 20s, but her ability was instantly apparent, and just a few years later she represented Czechoslovakia at Helsinki 1952 Olympic stage by storm. Shortly after watching her husband win 5000m, Dana was preparing to take to the field, but made a bee-line for her spouse and demanded to see his gold. When he duly produced it, she seized it, put it in her kit bag and said “I’ll take it with me for luck.”

Her first throw of 50.47m proved to be the longest of the day. When Emil tried to take some of the credit for inspiring his wife’s Olympic victory at her press conference, claiming that it was his victory in 5,000m that had “inspired” her. Dana’s indignant response was, “Really? Okay, go inspire some other girl and see if she throws a javelin 50m!”

Dana went on to finish fourth at Melbourne 1956 Olympics with 49.83m, before fighting her way back onto the podium at Rome 1960, at nearly 38 years winning silver with 53.78m to become the oldest woman ever to win an Olympic athletics medal. She also won the European title in 1954 and 1958 and, between those two successes, setting a new world record of 56.02m thus becoming the oldest female javelin thrower to do so.

Naturally Gifted Athlete

Emil though named by Runner’s World in 2013 as the greatest runner of all time, was not the most naturally gifted athlete. His lifetime best for 800m was 1:58.7; for 1,500m, 3:52.8. Even compared with his rivals, he was noticeably lacking in raw speed. Emil’s resting pulse-rate was in the mid-fifties; his blood pressure normal. So, it wasn’t his genes that made him exceptional. It was his dedication.

In contrast to the privileged types who had hitherto dominated Olympic competition, Emil was born in poverty. In the words of the great Australian coach Percy Cerutty, ‘He earned, and won for himself, every inch of a very hard road.’ Emil believed that ‘What a man wants, he can achieve.’ All it took was effort, persistence and a cheerful indifference to discomfort. ‘Pain is a merciful thing,’ he explained.

By mid-1950s he was doing up to 100 fast 400m laps a day, with 150m jogs in between. When Emil first developed his regime of high-volume interval training, his fellow athletes were appalled. ‘Everyone said, “Emil, you are a fool!” ‘But when he first won the European Championship, they said: “Emil, you are a genius!”’

Innovation and Commitment

Emil didn’t have a ‘secret’. He did have a scientific mind. He studied chemistry as a young man, and from the moment he took up serious running he explored hitherto untried ways of improving his performance. Early experiments included holding his breath until he passed out; eating vast quantities of dandelions and garlic; and drinking a mixture of lemon juice.

None of these specific experiments can be said to have had a lasting impact on modern practice among elite distance runners. But the mindset, the idea that the challenge of running faster should be tackled with ingenuity and empirical science as well as effort, and that no gain is too marginal to be helpful at the heart of contemporary sports science.

Emil’s training philosophy wasn’t just about pushing himself hard physically. It was about teaching his mind to shrug off pain and discomfort. Contemporaries considered him remarkable for training whatever the weather. ‘There is a great advantage in training under unfavorable conditions,’ he said, ‘for the difference is then a tremendous relief in a race.’

The more he did so, he believed, the more inner toughness he developed. ‘When a person trains once, nothing happens. When a person forces himself to do a thing a hundred or a thousand times, then he certainly develops in ways more than physical. Is it raining? That doesn’t matter. Am I tired? That doesn’t matter either. Willpower becomes no longer a problem.’

The more he did so, he believed, the more inner toughness he developed. ‘When a person trains once, nothing happens. When a person forces himself to do a thing a hundred or a thousand times, then he certainly develops in ways more than physical. Is it raining? That doesn’t matter. Am I tired? That doesn’t matter either. Willpower becomes no longer a problem.’

You take yourself off to boot camp, or the wilderness. You benefit from the altitude and the scientific back-up, but you also toughen yourself up mentally. When the moment of truth arrives in the stadium – or on the streets of your local half marathon – the resulting toughness stands you in good stead. At least it’s flat, and you’re not running through a blizzard.

If Emil did have a special physical gift, it was in his exceptional ability to recover from exertion. His pulse rate would return to normal very quickly after a hard race. More importantly, his muscles recovered quickly, especially as the years of mileage accumulated. These powers of recovery meant that he could shake off the exhaustion of an enormous training session in time to do it the next day.

One of Emil’s endearing qualities was his refusal to allow life’s inconveniences get in the way of his training. As a soldier, he used to jog on the spot-on sentry duty; years later, as a celebrity, he often jogged while being interviewed. Once confined to hospital by food poisoning, he sneaked into the kitchens to cook himself an illicit meal, then jogged in the hospital gardens.

Legacy of Emil

The author traced the legacy of the global celebrity whilst in Prague in 2013. Undefeated at 10,000m for six years, Emil dominated and revolutionized athletics. His clean sweep at Helsinki 1952 is unlikely ever to be matched. His self-developed system of high-volume interval training – first ridiculed, then widely imitated – transformed the way that elite distance runners train.

Emil was known for his friendly and gregarious personality and for his ability to speak six languages. He was regularly visited in Prague by international athletes he had befriended at competitions. His British rival Gordon Pirie described his home as “the merriest and gayest home I’ve been in.”

Emil won four Olympic gold and one silver whilst Dana secured one Olympic gold and one silver. The couple, Emil and Dana were the witnesses at the wedding of Olympic gold medalists Olga Fikotova and Harold Connolly in Prague in 1957. Emil had spoken to the Czechoslovak President Antonin Zapotocky to request a permit for Olga to marry the American Connolly, at the height of the Cold War and they received it within days.

Then there was his personality: witty, charming, kind. Fans liked his visibly agonized running style, which made him supremely dramatic to watch. Rivals loved him for his humor and sportsmanship. He transcended sport. He is also known for his unique and distinctive running style, facial expressions on the track and his posture.

Emil hung up his spikes in 1957 and continued in the Czechoslovak Army and rose to the rank of a Colonel in 1964. He also worked in the Ministry of Defence. In 1966, Emil hosted the Australian Ron Clarke when he visited Prague. Emil knew the bad luck that Clarke had faced; he held many middle-distance world records and had attempted to join his idol in the record books, but had fallen short of winning an Olympic gold. At the end of the visit, Emil gave one of his Olympic gold medals from the 1952 Olympics to Clarke.

Then his fame drained away, messily. A decade after his retirement, he was driven out of public life after the Soviet-led invasion in 1968. The man who had once been the world’s most famous sportsman became a shadowy figure. He spent years working as an itinerant laborer, living in a caravan, far from his home and his adored wife.

Later, President Vaclav Havel rehabilitated Emil in 1990 and conferred the national title ‘White Lion’, one of Czech’s highest awards. Emil and Dana were blessed with a marathon married life of 53 years. Emil was 78 when he died on November 22, 2000 in Prague. Emil was awarded the Pierre de Coubertin medal posthumously in 2000 and was among the first twelve athletes inducted into the IAAF Hall of Fame in 2012. A life-size bronze statue of Emil was unveiled at the Stadium of Youth in Zlin in 2014. Dana passed away on March 13, 2020 in Prague, having lived 97 years.

(The author is the winner of Presidential Awards for Sports and recipient of multiple National Accolades for Academic pursuits. He possesses a PhD, MPhil and double MSc. He can be reached at [email protected])