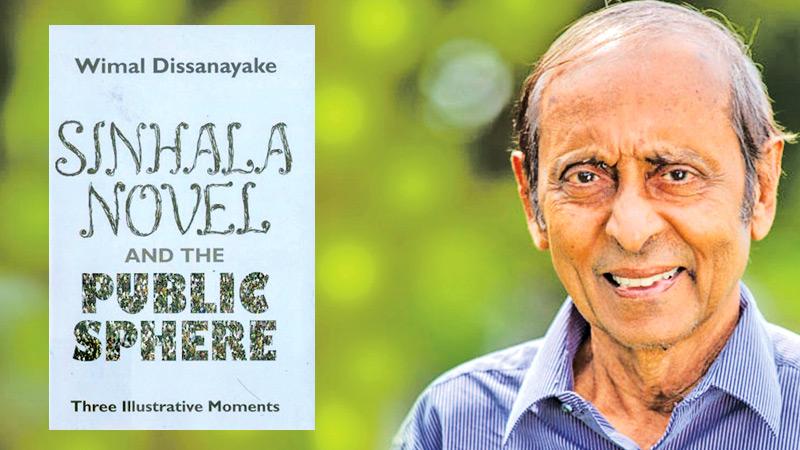

Book: Sinhala Novel and the Public Sphere: Three Illustrative Moments

Author: WimalDissanayake

Publisher: Visidunu Prakashakayo (Pvt) Ltd.

Pages: 214

If someone looks into the evolution of the Sinhala novel, he can identify three writers who contributed to the Sinhala novel to reach its present level. Piyadasa Sirisena, Martin Wickramasinghe and Gunadasa Amarasekara are considered to be three pillars of the Sinhala novel.

If someone looks into the evolution of the Sinhala novel, he can identify three writers who contributed to the Sinhala novel to reach its present level. Piyadasa Sirisena, Martin Wickramasinghe and Gunadasa Amarasekara are considered to be three pillars of the Sinhala novel.

A veteran Sinhala critic and poet Prof. Wimal Dissanayake in his book, ‘Sinhala Novel and the Public Sphere’, elaborates three illustrative moments in the Sinhala novel which are represented in the novels of Piyadasa Sirisena, the trilogy of Martin Wickramasinghe and the novels by GunadasaAmarasekara.

He focuses on one specific theme in it, related to the growth of the Sinhala novel. It is the relationship between the Sinhala novel and the local public sphere. The author discusses in detail the interaction of the Sinhala novel with public sphere.

The book consists of five chapters: the first, the public sphere as a Capacious Concept, the second, the public sphere in Sri Lanka. The third, PiyadasaSirisena and the discourse of Cultural Nationalism, while the fourth, Martin Wickramasinghe and the anxieties of modernity. Final chapter is Gunadasa Amarasekara and the representation of history.

Public sphere

At the outset, Prof. Dissanayake, describes the term ‘public sphere’ quoting a few writers and thinkers. As he mentioned, the German philosopher Jurgen Habermas is among foremost who popularised this term. Citing Habermas, he said, “He saw the public sphere as, ‘a domain of our social life where such things as public opinion can be formed (where) citizens…. deal with matters of general interest without being subject to coercion…. to express and publicise their views.”

This chapter is a scholarly analysis on the public sphere. There, he compares between nature and public sphere, religion and public sphere, and secularism and public sphere. He explains the public sphere through many points of view, and gives insights to it elaborating various aspects of the public sphere.

In the second chapter, he outlines the growth of the public sphere in Sri Lanka and point to its discursive distinctiveness and significant facets of its genealogy.

He focuses on some noteworthy features related to the concept of the public as it finds articulation among the Sinhalese in Sri Lanka. For instance, using the word ‘public’, he gives some word list in common Sinhala usage in which the meaning of each differs according to the adding word:

- Prasiddhadeshanaya – Public lecture

- Podudepola – Public property

- Mahajanapusthakalaya – Public library

- Jana mathaya – Public opinion

- Pathakajanathava – Reading public

- Podujanaayithiya – Public right

- Rajayeprakashanayak – Government publication

In this way, he investigates the diverse usages of the term public in general Sinhala discourse.

Role of Piyadasa Sirisena

The third chapter, Piyadasa Sirisena and the Discourse of Cultural Nationalism, dedicates to elaborate the role of Piyadasa Sirisena or ‘Father of Sinhala fiction’. There, he describes positives as well as negatives towards realism in Sirisena’s fiction, while presenting a brief biography of him:

“In terms of careful construction of stories, psychological complexity of character, credibility of experience and convincing fictional, his work left much to be desired. He wrote at the dawn of Sinhala fiction and such weaknesses as I have alluded to are only to be expected. However, Piyadasa Sirisena was a serious writer who wished to establish a vital connection between literature and the public sphere.” (Page 87)

He analyses Sirisena’s fiction as follows:

“Piyadasa Sirisena’s novels were intended to mobilise support for the course of the cultural national project and hence his various representational and rhetorical strategies merit closer study. For example, if one does a tropological study of all nineteen novels, one would realise that he uses tropes that draw on traditional imagery and association as a way of enforcing his rigid divisions of what is good and evil, constructive and destructive.

“He draws on classical prose writings such as the Pujavaliya and Saddharmarathnavaliya and classical works of poetry such as the Sandeshakavyas and KusaJatakaya for this purpose. This also constitutes, for him, a way of combining tradition and modernity in that he is deploying these classical themes and rhetorical locutions in modern contexts thereby coalescing the past and present in invigorating ways.” (Page 104)

Prof. Dissanayake keeps Piyadasa Sirisena at the right place on the ladder of the Sinhala novel.

Wickramasinghe’s trilogy

In the third chapter, Martin Wickramasinghe and the Anxieties of Modernity, he focuses on the trilogy of novels by Wickramasinghe – Gamperaliya (1944), Kali Yugaya (1957) and Yuganthaya(1949) which signals the second illustrative moment in the conjunction of Sinhala fiction and the public sphere.

In the first half of this chapter, Prof. Dissanayake outlines the main characteristics of Wickaramasinghe’s trilogy and their relativity to the modernity. He describes their connectivity to the public sphere:

“In examining the relationship between Wickramasinghe’s trilogy and the public sphere, it is important, I think, to invoke the concept of the knowable community enunciated by the eminent literary critic Raymond Williams. This is at once a social-historical and literary-textual concept that has a direct bearing on our understanding of the novel in the way it generates social meaning.” (Pages 137 - 138)

Prof. Dissanayake goes on to describe what it means by ‘knowable community’. Next, he analyses the significant aesthetics and nuances of Wickramasinghe’s fiction:

“He directs us to what we should see as well as how we should see, thereby enhancing the narrative intelligibility of his fiction. Over ninety percent of his natural descriptions and urban descriptions focus on the play of lights and shadows. The sun, moon, stars as well as oil lamps, lanterns, electric lights, street lamps, lights from the harbour and so on find repeated articulation in his fiction.

“It is as if he is seeking to emphasise the illuminatory significance of these passages of descriptions in terms of the transcoded meanings of the novels. Through his concentrated focus on the visible word, the transient objects and events, by penetrating deeply into contingencies of time and place, he was attempting to produce a new visibility, fuller and deeper than earlier one. These descriptions enable him to position the reader in history by situating the observer and observed in close intimacy.

“Wickramasinghe, through his reconfigurations of the immediate visible world, was able to redeem the physical reality objects and events from everyday banality, and invest them with cultural meanings that connected well with the human significances of his novels. The seemingly inconsequential details of the physical world yielded, in his able hands, the newer shapes of contemporary reality.” (Page 151)

Gunadasa Amarasekera’s novels

In the last chapter, Gunadasa Amarasekera and the Representation of History, Prof. Dissanayake expounds the characteristics of Amarasekera’s novel and his discourse with society. The following is how he analyses Amarasekera’s novel:

“In the seven novels of GunadasaAmarasekera, which are the focus on this essay, what we find is the careful representation and textualisation of the growth and decline of the local middle class during the past six decades or so.

“He delineates with great cogency the fact that within progress are embedded the seeds of decline and within decline are embedded the seeds of progress. This is an indication of the way in which dialectical processes operate in through social phenomena.”

Prof. Dissanayake describes the seven novels on the theories of Georg Lukacs. He gives us a better picture to understand Amarasekera’s seven novels.

The three illustrative moments of Sinhala fiction are ideal occasions to discuss the Sinhala novel and the public sphere, because those three writers are, one way or another, connected to the didactic fiction, though the last two are not directly associated with it.

This book enlightens the reader on the part of three landmarks of Sinhala fiction.