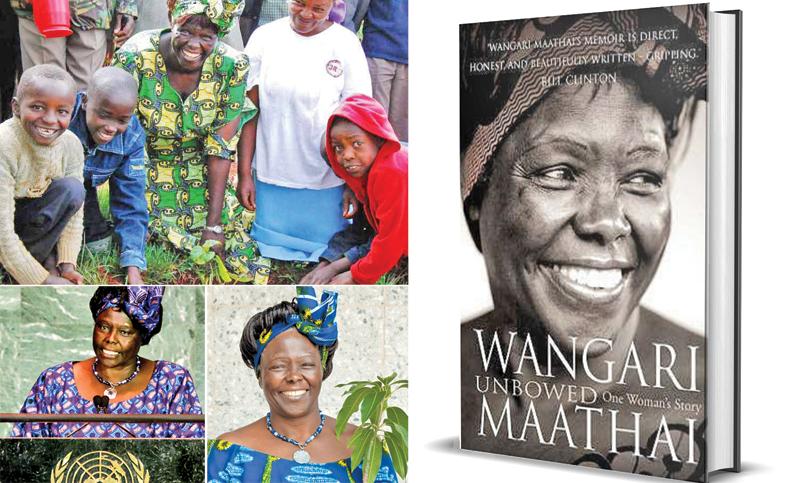

Title – Unbowed

Author – Wangari Maathai

Publisher – William Heinemaan, London

Unbowed is a memoir by Wangari Maathai, Nobel Prize winner for Peace in 2004, a Kenyan politician, a women’s and environmental activist. In this book she recounts her extraordinary journey from her childhood in rural Kenya to the world stage.

Though she is known as a Nobel prize winner, it is her environmental activities that made her known the world over. She founded a unique environmental conservation project, Green Belt Movement in 1977.

When colonization began in Kenya, the majority of the land was covered with forests. But theBritish colonialists started deforestation practices for building and farming, especially for economic crops such as tea and coffee in the 1880s. This resulted in desertification, a pollution of natural resources and climate change disasters.

Hence, she started a people centred project to plant trees to eliminate poverty thinking that the real reason for the poverty of the villagers was deforestation. “Poor people will cut the last tree to cook the last meal,” she once said. “The more you degrade the environment, the more you dig deeper into poverty.” This is how the Green Belt Movement was born in 1977.

Village life

Born on April 1, 1940 Wangari Maathai grew up in Nyeri County, located in the central highlands of Kenya. She had a bucolic childhood spent in the rural Kenyan countryside. As with every memoir or autobiography, the author starts the book with her childhood experiences:

“I was born the third of six children, and the first girl after two sons, on April 1, 1940, in the small village of Ihithe in the central highlands of what was then British Kenya.

My grandparents and parents were also born in this region near the provincial capital of Nyeri, in the foothills of the Aberdare Mountain Range. To the north, jutting into the sky, is Mount Kenya.” (Page 3)

The book gives us fascinating insights into life of Wangari Maatha and her hometown, Nyeri:

“At the time of my birth, in 1940, there were still people who had not become Christians and competition for converts among the many churches that had been established was intense. In and around Nyeri, the Catholics, the Prsebyterians, and the Independent Church were very active.

Those who had not embraced Christianity, who still held on to and advocated for local customs, were called Kikuyus, while those who had converted were called Athomi. Literally translated, this means ‘people who read.’

The book they read was the Bible. One of the first local language translations of the Bible was into Kikuyu, which made the Christian teachings much more accessible.” (Page 10 – Page 11)

Transformation of traditional society

Wangaari Mathaai is a member of a Kikuyu tribal society, and a Christian in religion. She describes the socio–cultural environment that she had to grow up in her village:

“In general, local Kenyans who converted to Christianity were given preference within the British colonial administration and were often appointed chiefs and sub chiefs in villages and towns. In addition, the athomi culture was presented by those who embraced it as progressive, its members moving forward into a modern while the others were presented as primitive and backward, living in the past.

The Athomi culture brought with it European ways and led to profound changes in the way Kikuyus dressed and adorned themselves, the kinds of food they ate, the songs they sang, and the dances they performed. Everything that represented the local culture was enthusiastically replaced. Millet gave way to maize, and millet porridge, then the most common Kikuyu drink, was displaced in favour of tea.

As the crops changed, so did the tools used for agriculture and cooking: Corrugated iron pots replaced earthen ones, plates and cups replaced calabashes, spoons replaced fingers and sticks. Clothes of animal skin were put aside in favour of cotton dresses for women and shirts, shorts and trousers for men.

“….. A nearly complete transformation of the local culture into one akin to that of Europe had taken place in the generation before I was born.” (Page 11)

There she describes how her grandfather’s dress was:

“Among the critical mass of Kikuyus in the central highlands who had converted to Christianity by the time of my birth were my parents. Because my parents were athomi, they dressed like Europeans, as did I, because I was a child of ‘those who red.’ I remember seeing some ‘Kikuyus’ in and around Ihithe, including my paternal grandfather, Njugi Muchiri, wearing either a goat skin or a blanket that hung over his shoulders and fell long to the ground.” (Page 12)

Education

Wangari Maathai had a bucolic childhood spent in the rural Kenyan countryside and was sent to St. Cecilia Intermediary, a mission school, for her primary education. After that in 1964 she went to the United States, and there she attended Mount St. Scholastica College in Atchison, Kansas, majoring in Biology.

She obtained a degree in Biological Sciences from it in 1964, and then took a Master of Science degree from the University of Pittsburgh in 1966. Thereafter, she pursued doctoral studies in Germany and the University of Nairobi, before obtaining a Ph.D. (1971) from the University of Nairobi, where she also taught veterinary anatomy.

The first woman in East and Central Africa to earn a doctorate degree, Professor Maathai became chair of the Department of Veterinary Anatomy and an associate professor in 1976 and 1977 respectively. In both cases, she was the first woman to attain those positions in the region. She highly admires the value of education in her memoir:

“Education, of course, creates many opportunities. In Kenya, for most people of my generation and after, a high school education or a college degree is a guaranteed ticket out of the perceived drudgery of subsistence farming or the cultivation of crash crops for little return. I, too, got this ticket out, but I never severed my connection to the soil.” (Page 71)

In the chapter titled Foresters Without Diplomas she presents the environmental issues in her hometown and how the Green Belt Movement was founded:

“When I went home to visit my family in Nyeri, I had another indication of changes underway around us. I saw rivers silted with topsoil, much of which was coming from the forest where plantations of commercial trees had replaced indigenous forest. I noticed that much of the land that had been covered with trees, bushes and grass when I was growing up had been replaced by tea and coffee.” (Page 121)

Green Belt movement

The facts she points out with regard to the deforestation are very much similar to the Sri Lankan situation too:

“I remembered how the colonial administration had cleared the indigenous forests and replaced them with plantations of exotic trees for the timber industry. After independence, Kenyan farmers had cleared more natural forests to create space to grow coffee and tea.” (Page 123)

In fact, Wangari Maathai presents us with a unique model to improve our forest cover in a very practical manner. This how she founded the Green Belt Movement:

“The concept of tree planting, however, remained alive. In 1977, two years after the women’s conference in Mexico City, the National Council of Women of Kenya (NCTWK) invited me to talk about my experiences at the Habitat I meeting and shortly afterward elected me a member of its Executive Committee as well as its Standing Committee on Environment and Habitat.

“Within this setting I again proposed planting trees as an activity the NCTWK could take on to assist its rural members and so meet the women’s needs. The membership agreed and encouraged me to put my idea into action.” (Page 130)

Now this project mobilized Kenyans, particularly women, to plant more than 30 million trees, and inspired the United Nations to launch a campaign that has led to the planting of 11 billion trees worldwide. And more than 900,000 Kenyan women benefited from her tree-planting campaign by selling seedlings for reforestation.

Her death

Wangari Maathai died in 2011 after a battle with ovarian cancer. In 2012, a community garden project for local residents was opened in Washington, DC, and it was named in memory of Wangari as Wangari Gardens which consists of over 55 garden allotments.

When she was at the death bed she reiterated her wish that she must not be buried in a wooden coffin — thereby reaffirming her life-long battle to save trees and the rest of the environment. Hearing her death, the Nigerian environmental activist, Nnimmo Bassey said, “If no one applauds this great woman of Africa, the trees will clap.”