In a hurried visit to the Bodh Gaya Archaeological Museum in December 2015 just outside the Mahabodhi Temple, a description of one of the artefacts – a fence-like structure in granite – took me by surprise. While referring to the Mahabodhi Temple, it noted, “A monastery was also built by King Meghavarman of Sri Lanka for his Bhikkus”. The artefact was supposedly a remnant of this monastery.

The world knows about the iconic Maha Bodhi Temple, but hardly anyone knows about what this Lankan king had built in its vicinity, why this was done and what it means. Over the next few months, this single reference directed me to numerous ancient sources, colonial period recordsand translationsand later to an ongoing study on Buddhist pilgrimage across international bordersover time.

The world knows about the iconic Maha Bodhi Temple, but hardly anyone knows about what this Lankan king had built in its vicinity, why this was done and what it means. Over the next few months, this single reference directed me to numerous ancient sources, colonial period recordsand translationsand later to an ongoing study on Buddhist pilgrimage across international bordersover time.

Kithsirimevan

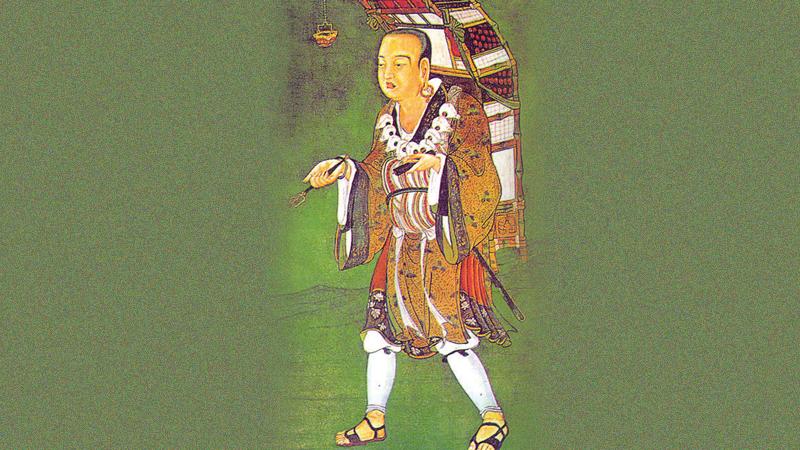

King Meghawarman is also known as Sirimeghavanna, Kirthi Sri Meghavarna and more commonly in Sinhala as Kithsirimevan. He ruled in the Anuradhapura period – in the 4th century – and is credited in local sources for his sponsorship of Buddhist infrastructure and is also believed to have welcomed the Buddha’s tooth relic to Lanka. But he does not occupy the public imagination, or the historical consciousness of the country or the Sinhalas as do kings, such as Dutu Gemunu, Vijaya Bahu the First, Parakrama Bahu the Great and even mythical characters, such as Rawana.

This is perhaps due to the warrior status of the latter kings while Kithsirimevan was a monarch of piety and diplomacy. But he is singularly important for his successful project of cultural power projection from Anuradhapura to the court of Samudra Gupta and through him, institution-building in Bodhi Gaya. He effectively built, as the Bodhi Gaya Museum narrative says, a large monastery for monks from Sri Lanka, who visited the location on pilgrimage or for more long-term religious pursuits.

But what were the politics behind this project? The earliest reference tothis construction effort is from Hiouen-tsang (602-664 CE). He was a Chinese Buddhist Bhikku, scholar and traveller. When describing the Bodhi Gaya in 629 CE, he notes how this construction effort began.

According to him, when the brother of an unnamed Lankan king visited ‘India’. Bodhi Gaya, he was not treated well for being a foreigner. The king, upon hearing of his brother’s misadventures, wanted to build monasteries for Lankan pilgrims to rest all over ‘India.’

According to Hiouen-tsang, the Lankan king sent gifts of precious jewels to the king of ‘India’ and asked for permission to build monasteries in his land – in places that were important in the life of the Buddha. However, instead of allowing the construction of Lankan cultural and spiritual edifices all over ‘India’, the king gave permission to build one monastery in a place of the Lankan king’s choice.

Bodh Gaya was selected as it was believed to be the site of the Buddha’s Enlightenment. Hiouen-tsang notes that a copper proclamation established in the completed monastery had asserted, “The Bhikkus of my country will thus obtain independence and will be treated as members of the fraternity in this country. Let this privilege be handed down from generation to generation without interruption.”

Long term effect

If this report is taken seriously, what is described here is not a simple one-off construction of a simple building far away from the shores of Lanka, but a carefully planned and well-funded exercise in cultural and political power projection. It was intended to last well beyond the time of its initiator. Hiouen-tsang’s description of the building and the activities he had witnessed in it, suggest that these long-term political and cultural objectives of the monastery had been met when one considers,his descriptions are from three hundred years after the monastery was built.

As he notes, “Outside the Northern gate of the wall of the Bodhi tree is the Mahabodhi sangharama. This edifice has six halls, with towers of observation of three storeys; it issurrounded by a wall of defence 30 or 40 feet high. The utmost skill of the artist has been employed; the ornamentation is in the richest colours. The statue of the Buddha is cast in gold and silver, decorated with gems and precious stones. The stupas are high and large in proportionand beautifully ornamented; they contain relics of the Buddha.”

Obviously, this was not merely a monastery, but a religio-cultural institution that was meant to withstand the ravages of time; a place that was meant to impress and was spatially marked as an independent entity and meant to be defended as a specific cultural and political space. Perhaps, that is the reason it still existed at the time ofHiouen-tsang’s visit and its legend was still known. Hiouen-tsang came to India in 629 CE during the time of Emperor Harsha. His descriptionand what he saw can be timed with a significant degree of accuracy.

Further records

Another seventh century Chinese source, the Hing-tchoan written by Wang Hiuen-ts’e presents specific information on those involvedin this construction effort which also allows for its timing to be ascertained more accurately.

Crucially, his records corroborate the general story reported by Hiouen-tsang. Hiuen-ts’e was a Chinese military officer and Buddhist pilgrim who is known to have travelled to ancient India at least four times during which time he maintained extensive records.

He identifies the Lankan king as Chi-mi-kia-po-mo, which means ‘cloud of merit,’ and has been identified as a reference to Kithsirimevan. His ‘Indian’ counterpart is referred to as San-meou-to-lokiu-to, who has been identified as Samudragupta. Samudragupta and Kithsirimevan are known to historians. Based in Patali Putra, Samudragupta’s reign lasted from 335 to 380 CE while Kithsirimevan who was based in Anuradhapura ruled from 352 to 379 CE.

The timing that can be inferred from Hiuen-ts’e’s references makes the two kings contemporaries and suggests that Kithsirimevan’s monastery was a fourth Century CE state enterprise spanning significant geographic, linguistic, cultural and political borders.

This monastery is not merely a lingering reference in seventh Century CE Chinese travelogues. Archaeological evidence unearthed in the late 19th century has also established its physical existence.

Alexander Cunningham, a British Army Officer in the colonial period who had an interest in the archaeology and history of India notes that the walls of the monastery were thirty to forty feet high, offering an initial sense of its scale even in its ruined state in the late 1800s.

What he proceeds to describe is a massive structure closely in keeping with what had been described 12 centuries earlier by Hiouen-tsang: “Here, in November 1885, Mr Beglar and myself discovered the remains of a great monastery, with outer walls nine feet thick and massive round towers at the four corners. One tower of this enclosure is still standing on the west side in an old Muhammadan burial ground. The outer line of wall with the south-west tower is still traceable. There were four towers at the four corners. Three intermediate towers on each side, making 16 towers.”

Layout of the monastery

Cunningham describes that the overall layout of the monastery “consists of 36 squares, six on each side, of which the four corner squares are assigned to the corner towers and the four middle squares to an open pillared court containing a well. Along-covered drain leads from the well to the outside of the walls on the north-North-West, ending in a gargoyle spout in the shape of a large crocodile’s head, of dark blue basalt, richly carved.”

The point I want to make in presenting this description today is simple. At a time when many people in Lanka are engrossed in resurrecting stories of mythological characters, such as Rawana, his legendary aircraft and his mythological adventures as evidence-based ‘history’, there are crucial moments of our distant past that have been well-documented – as in the case of Kithsirimevan’s monastery.

But such documentation cannot be seen in local sources. But the details that do exist– such as in the seventh century Chinese records and the late 19th century British colonial records referred to earlier–hardly receive any attention in formal Lankan historiography or popular imagination.

However, a close study of these historical events would indicate important aspects of ancient diplomacy, international relations, statesmanship, politics of wealth and cross border projection of cultural power, which could possibly help us significantly rethink South Asia’s past.

Also, one must wonder why Kithsirimevan is not presented in the same ‘heroic’ mould as other kings in the Pali chronicles even as his local religious pursuits are referred to.

This is an important historical investigation that needs to be undertaken. On the other hand, narratives such as these can also offer fertile resources for imaginative creative writers to think of crafting epic works of fiction on the lines of well-known global examples, such as Umberto Eco’s The Name of the Rose and The Prague Cemetery.

Particularly in the realms of fiction, such information offers endless possibilities. However, it is unfortunate neither of these historical or fictional journeys have been undertaken seriously in Lanka. This is simply because we are obsessed with fiction as history and amnesiac when it comes to well-documented accounts of the past.