After two months of quarantine and social distancing, it is easy to see that people have taken to social isolation in quite different ways to one another. Some go crazy due to lack of person-to-person contact while others find it much easier and may even consider the current situation to be nothing less than an excuse to do exactly what they have wanted to. But while those people could simply be a bit introverted, there is a serious phenomenon in Japan that has taken that reclusive attitude to the illogical extreme. This condition and those affected by it, collectively known as “Hikikomori” have been completely isolating themselves from society for years, long before even a hint of a pandemic.

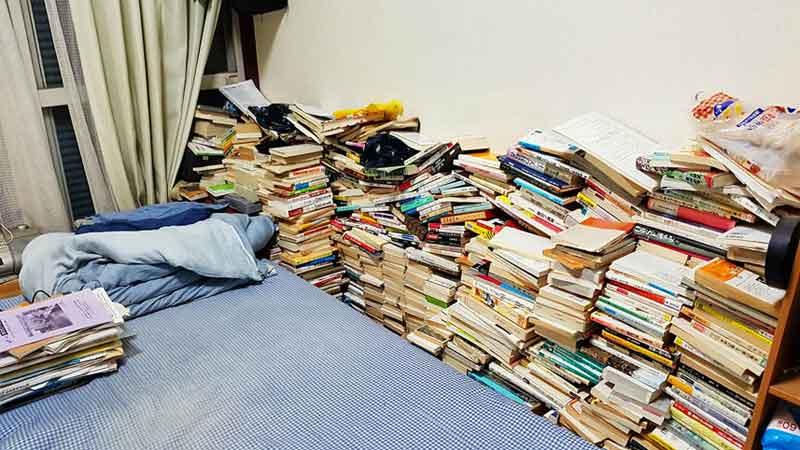

As a known form of severe social withdrawal, hikikomori has been described by the Japanese Ministry of Health as a condition affecting mainly adolescents and young adults in which they refuse to leave their home and do not participate in society for at least six months. This phenomenon has been going on for decades in Japan now and the number of those who can be described as a hikikomori have been identified by the Japanese government to be at least a million though people have estimated the real number to be anywhere between two and ten million. While the issues they pose might be in the individual scale for now, there are estimated 600,000 Japanese between the ages of 40 and 60, all of whom will soon lose their primary care givers. While there is no concrete explanation for this odd and potentially dangerous behaviour, it is not all that surprising considering Japan’s rigid social structure and their extensive history of isolationism. Despite the stereotype of respect in Japan, there is a deep lack of respect for the individuals. Those who are not deemed useful to society or their family are seen as having no value. The stigmas surrounding Hikikomori and the insensitive attempts at fixing the issue only served to further drive them into a corner and out of society. While most see them as lazy young people with attitude problems who stay in their rooms all day, the reality is that most of the time, they have been forced into shutting themselves away.

While this is primarily a Japanese issue, it has become clear that it is no longer faced by Japan alone.

Countries of greatly different cultures, such as Hong Kong, Oman, Spain, India and even the US and Britain which have a strong sense of individualism, have developed cases of social withdrawal resembling Hikikomori.

However, this increased isolationist attitude has its benefits which have become apparent in the current pandemic. Japan is the only G7 country where the Covid-19 pandemic hasn’t caused any serious problems. This is especially notable when taking into account that Japan’s cities have an especially large population density and their first case has been reported way back in January.

In addition to the Japanese being naturally fearful of common infectious diseases long before Covid-19, the youth self-isolation long before it was needed has slowed the spread of the virus in the country.

It is important to respond quickly to the situation of Hikikomori by once again integrating such people to society, little by little. Much like most psychiatric conditions, solutions to this depend on those afflicted recognising their condition and working towards developing points of contact with the outside world on their own.

Hikikomori and similar social recluses might not seem too problematic to society at the first glance, however, regardless of personal preference, extended social withdrawal can lead to depression, fear of others and even a dangerous resentment towards those who do remain close.