A year ago, the country withstood a serious challenge to its governance and government. The Constitutional Coup launched by President Maithripala Sirisena marked a low point in the constitutional and political development of the country in as much as the decision of the Supreme Court and the role of civil society and other political actors in reversing it, held out and indeed holds out the hope that at the end of the day, democratic principles, practices and institutions lie firmly embedded in our body politic.

The actions of President Sirisena ran fully counter to the reform platform and positions he had espoused in his election campaign of 2015. Leave aside the basic tenets of democratic governance, then and indeed thereafter, the trend was towards restoring the balance of political and constitutional power in favour of Parliament and away from the executive presidency, the powers of which were to be considerably clipped, if not the office abolished. Maithripala Sirisena, who had been shopping around for a new Prime Minister even before the debacle of the Local Government elections in February 2018, now proceeded, second time around, to get the Prime Minister of his wishes.

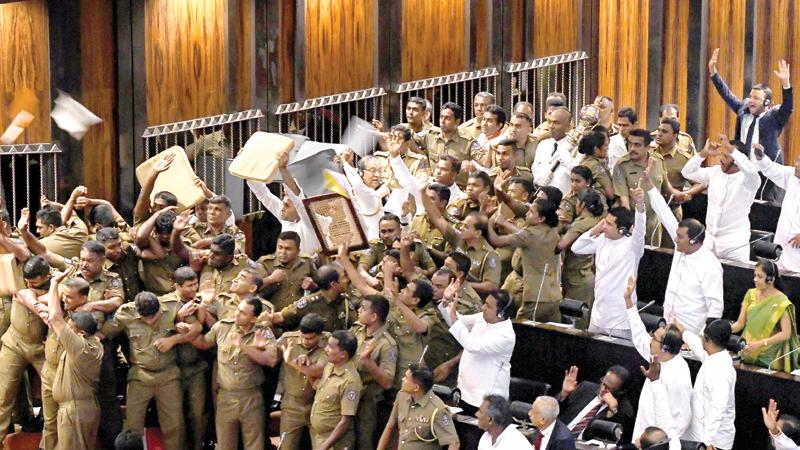

He sacked Ranil Wickremesinghe as Prime Minister, appointed his erstwhile rival for the Presidency Mahinda Rajapaksa in his place and prorogued Parliament, in a not so transparent effort to buy time to buy the votes to support his new Prime Minister in the House. He went further and set a date for a general election, oblivious or aware and not giving a damn, that Parliament could not be dissolved before four and a half years of its term lapsed unless Parliament by a two-third majority requested its own dissolution.

To the President of the Republic it was as if the Nineteenth Amendment, the centerpiece of his legislative programme, did not exist. Sirisena’s actions were classically that of the executive president of yore - not that of a reformer determined to put the country back on the track of democratic governance.

Despite media speculation, blatant and not so blatant politicking for the candidacy, Sirisena is to be a one term President. Despite sighs of relief and in some quarters, hearty applause, Sirisena will not be a candidate for the Presidency.

Yet this begs the question of how someone who has been so completely out of his depth, has not been held to account for his actions that amount to the blatant and wholesale sabotage of the promise and potential performance of his reform government of 2015? Perhaps it will come after November 16. It surely must.

In hindsight, the coup that failed has been seen as a victory of the institutions of democracy. To begin with, the executive went to war within itself with President against Prime Minister and with the latter having the law and the constitution on his side. Moreover, he stood firm and did not yield as perhaps the President and his new Prime Minister may have expected and the Speaker performed yeoman service in the defence of parliamentary rights and privileges.

Eventually, the Supreme Court decided, and in a landmark judgment, restored Ranil Wickremesinghe as Prime Minister. The Judiciary did not fail us. As the Executive and Legislature battled it out on the floor of the House, the Judiciary stepped in to conclusively save the day by protecting the constitution and the country.

The issue is as to whether this was a decision of the Court heavily contingent on the personality and temperament of the Chief Justice and key judges of the Supreme Court or as to whether this signaled a new phase in the life of the Court – a phase in which it would demonstrate its independence and impartiality and put paid to the accusation that it was and is, executive friendly. Do we want to find out?

And complementing the stance of the Court was that of civil society. The demonstrations against Sirisena’s actions were especially heartening as were the posters and placards that read that opposition to his actions was not on the basis of UNP party affiliation or support for Ranil Wickremesinghe per se but support for Parliament and for upholding the Constitution. In this respect, 2015 had succeeded more than in name. It went beyond, to remind and reinforce Sri Lanka’s commitment and devotion to its democratic moorings.

In a sense, therefore, a year after the coup, the effort that went into its defeat has yet again to be mounted in the Presidential election. Once again it is a question of clearly establishing the country as one of laws and not of arbitrary dictates. Furthermore, the way things are done are just as important as what is done – ends do not justify means.

As Sri Lanka prepares itself to elect a new president, it would do well to buck the seemingly global trend of populism and authoritarianism, of the yearning for strong and decisive leadership.

The two main candidates in the election have so far talked about poverty and development, of discipline in respect of both and of constitutionalizing economic and social rights. Not a word on political and civil rights, which have been made more acute by the shrill denunciations and exhortations of Islamophobia, so utterly Goebelsian in its design and propagation. The coup against the constitution sought to overthrow basic and hallowed principles of governance in a sordid short-cut to government by executive convenience.

Let it be the low point in our political and constitutional evolution, for now and all time. And let us get on with the unfinished business of the reform package of 2015.