The politics of Sri Lanka have undergone a great shift within the last two decades. This article is about this great paradigm shift in the political landscape of Sri Lanka that has taken shape since the late 1990s, galvanized after the victory of the armed conflict in 2009, and of which the major manifestation was January 8, 2015. Today, despite the claim by the Sri Lanka Podujana Peramuna (SLPP) and the old leftist albatrosses sailing along with it, progressive politics are represented not by this faction, but by a large number of smaller parties led-by the United National Party (UNP). This view is new, and does not seem to resonate significantly with the UNP leadership either. But it is worth exploring the idea with some analytical detail and historical perspective.

Conservative vs. progressive camps

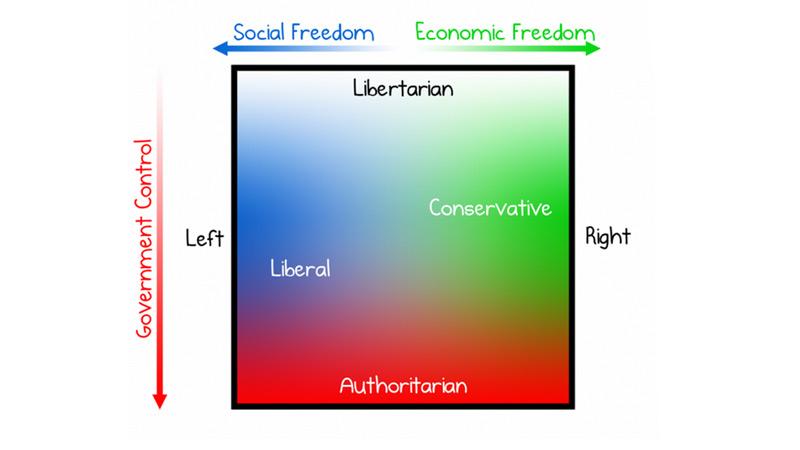

In many democracies, politics is crystallized around two broad ideologies that are called the right and the left. These two ideologies form broad platforms that represent different worldviews, priorities, way of doing things, support bases, and slogans etc. In France, where the two terms were first used to define political positions after the French Revolution, the “Right” consisted of those who sat to the right of the chair and supported the King, the old regime. Therefore, they were called “the party of the order”, as they wanted to preserve things as they were. In other words, they became the Conservatives. In the US, this ideology of supporting the order and upholding tradition over innovation, were called Republican. On the other hand, the Left represented the spirit of the Revolution and the desire for change and innovation. They were known as the Movement in France (later, socialists), Labour in the UK, and the Democrats in the US. This left-right has become a political spectrum between, ‘equality’ on the left and ‘hierarchy’ on the right. So the progressives, leftists or labour as the name suggests, would strive to achieve equality by changing the existing order, while the right, the conservatives, or republicans would guard against such change from happening to preserve the existing order. These ideologies manifest themselves in economic, social and political rights.

Left and Right in Sri Lanka

Sri Lanka inherited this political dichotomy as early as its first ever election in 1947. The United National Party, on the Right, formidably represented the ‘Order’, with an elitist but benevolent nationalist like D.S. Senanayake at the helm. On the other hand, the Left was led by Dr. N.M. Perera of the Lanka Sama Samaja Party (LSSP), who was a revolutionary. However, the Left could not form a government until the SLFP was formed by a cross-over conservative in the form of S.W.R.D. Bandaranaike, who was a great unifier of the scattered Left. Ever since then, SLFP has been the base for Sri Lanka’s Leftist political parties. The SLFP was considered the largest party on the Left, and formed coalition after coalition, uniting the scattered progressive camp. This broad coalition building was seen in 1956, 1960, 1970, 1994 and 2005. Over five decades, the SLFP provided leadership to an array of leftist parties from the old-left such as the LSSP, and even the JVP more recently, helping the smaller parties to become part of the Government. This type of coalition-building is a typical characteristic of the progressive camp. Their rhetoric was welfare-oriented and marked by a popular version of nationalism.

On the other hand, the ‘Right’, was owned by the UNP, the largest single party. The UNP was the party choice of elites, the business community, the rural poor and and importantly, the religious establishment.

Shifting support bases

The central theme of Sri Lanka in the decades of 1990s and 2000s was the threat of terrorism and ways to end it. Since the election of Chandrika Kumaratunga as President, and with Ranil Wickremesinghe becoming the Leader of the UNP, there was a general consensus that the ethnic struggle and its violent expression in the form of LTTE terrorism, needed a political solution, rather than a military one. This stance cost the UNP dearly, as what became the Sihala Urumaya was a breakaway faction from the UNP, but ended up supporting the UPFA led by Mahinda Rajapaksa. The idea that the UNP held until early 1990s, was that there was no ethnic issue in Sri Lanka. The position of the party was that Sri Lanka was facing a terrorist problem, as once declared by President Ranasinghe Premadasa. However, the shifting ideology from war to peace within the UNP alienated some hardcore nationalists who formed the Sihala Urumaya, that went on a short political journey alone, before joining hands with the UPFA in 2005, in its metamorphosed form of the Jathika Hela Urumaya. With the war victory in 2009, these trends galvanized and the UPFA, and its leader, Mahinda Rajapaksa became the ultimate manifestation of the conservative camp that represented the ‘order’ (against terrorism) and hierarchy (its family orientation).

An easy comparison can be made between the UNP of 1977 and the Sri Lanka Podujana Peramuna (which was formed by the Rajapaksa family) in 2018 in terms of their support bases, as per the following chart.

As the chart above shows, the traditional support bases and themes of the UNP are now owned and harnessed by the SLPP. This manifests a change that took place gradually, and culminated in 2009.

The role of the new progressive camp

As the Rajapaksa camp has now taken control of the Conservative discourse, it is, by default, up to the rest of the parties to represent the democracy-loving, reform-oriented progressive rhetoric that is marked by a strong welfare agenda. As we have seen in 2015, when a party is on the progressive side, it is quite important for them the build broad consensus and platforms for many small parties, interest groups, intellectuals and civil society to come together. Again, contrary to popular belief, it is this broad coalition-building that brought about the 2015 victory of the UNP-backed candidate.

Today, the Rajapaskas have a political party of their own. That party, despite some old school leftists, who are converts to neo-conservatism, and the party’s declared ‘centrist’ label, is a truly conservative party dressed up like a progressive party. Important, therefore, is that the UNP-led camp chooses a candidate who can build a large coalition with all progressive parties and groups. Going by the data of which traditional vote bases the SLPP garnered in the 2018 local government election, the recent claim that the UNP can win an election by making a call to their traditional hardcore membership is an illusion. A great unifier of scattered forces in the progressive camp is the need of the hour.