In the global history of cinema 2018 was nothing short of a fabulous year. According to ‘Time’ magazine of January 21, 2019, global movie box office earnings in 2018 amounted to US$ 41.7 billion. This is described as an all-time high.

When everything is said and done, we have just passed two milestones in the field of indigenous cinema.

On January 21, 1947, the first Sinhala language film, Kadavunu Poronduwa (The Broken Promise) premièred, marking the birth of Sri Lankan cinema.

On January 21, 1947, the first Sinhala language film, Kadavunu Poronduwa (The Broken Promise) premièred, marking the birth of Sri Lankan cinema.

Again, 25 years later, on January 21, 1972, the National Film Corporation came into being.

Given such a context, January seems pre-eminently the right time, to talk about Sri Lanka cinema.

When the Sri Lankan cinema had its birth 72 years ago, the world was in the throes of a global war. Although World War Two, had ended formally in 1945, its frightening echoes were still around. In Sri Lanka, near-universal employment and war-time inflation ensured a steady flow of cash, bringing in its wake a euphoric sense of sudden affluence.

The ever-present threat of death and destruction through war, though muted to an undertone, unleashed a frenzied indulgence in sensual pleasure. (This attitude is defined as Hedonistic Philosophy, which indicates that men seek a pleasure-foremost way of life, when there is a vague feeling of possible sudden death.)

The primary form of popular entertainment available to the masses at that time was, of course, the legitimate theatre. In the new centres of human settlement, that had been called into existence, due to the needs of the war-effort, the travelling Theatrical Companies received an adoration that verged on the religious.

The Sinhala actors and actresses who became mass idols of the day, could not cope adequately with the ever-burgeoning demand for their plays. The ‘live’ presence of a given actor or actress could happen only at one place at one time.

If the Theatre-companies were keen to rake in the available shekels in a larger volume, they had to create a method of multiplying the appearance of those actors and actresses, so they could perform simultaneously at several centres.

Cinema held the key to the solution of their problem. Turn the stage-play into its photographed version – have several copies of it made, and you get a simultaneous audience for your play, all over the Island (and even beyond). This exactly was the thinking that resulted in the Birth of Sinhala Cinema.

Cinema held the key to the solution of their problem. Turn the stage-play into its photographed version – have several copies of it made, and you get a simultaneous audience for your play, all over the Island (and even beyond). This exactly was the thinking that resulted in the Birth of Sinhala Cinema.

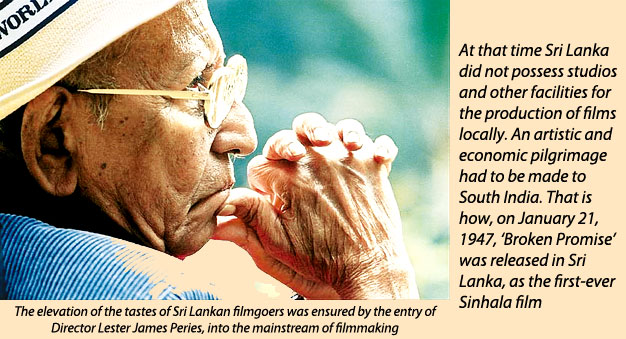

At that time Sri Lanka did not possess studios and other facilities for the production of films locally. An artistic and economic pilgrimage had to be made to South India. That is how, on January 21, 1947, ‘Broken Promise’ was released in Sri Lanka, as the first-ever Sinhala film.

Though these pioneers were moved by economic (purely monetary) urges, we have to be grateful to them, for their gesture. The persuasion to make the first Sri Lankan (Sinhala) film was not quite cultural or aesthetic-but almost entirely material. Be that as it may, they created history as the group that brought the first Sinhala speaking film into being.

Quite early in the history of Sri Lankan film, I was, the first critic to assess the achievement of Sinhala films at an international level. I say this with proper and due modesty, since it was the first English Article on cinema in Sri Lanka. I contributed this piece to the Observer Pictorial for 1950. Today, I just cannot imagine, how I had been so scathing at that time. Incidentally, it was (perhaps cynically) titled “The Sinhalese film – a wife and five puppets.” My key concept was that the raising of the level of taste of our filmgoers is urgently needed.

Today too, I return to that theme. The elevation of the tastes of Sri Lankan filmgoers was ensured by the entry of Director Lester James Peries, into the mainstream of filmmaking in Sri Lanka. His cinematic talent had evolved entirely within the film-discipline. He did not arrive via the legitimate theatre, as the earliest Sinhala filmmakers did. His Rekhava (The line of destiny) of 1956, was almost entirely shot outdoors. Despite the frustrating box-office failure, Rekhava asserted itself as the trend-setter. Lester acquired the status of the ‘Cinematic Establishment’ of Sri Lanka.

Foreign embassies

In this brief survey of the passage of Sri Lankan cinema from 1947 to our own day, it is quite sufficient, I believe, to state, that the advent of Lester James Peries’ cinematic presence, has been the most significant hinge-event that provided the indigenous cinematic tradition, the dynamism it needed to vitalize its progress.

In the subsequent decades, Sri Lankan film tradition flourished into a cultural force to be reckoned with when Director Lester James Peries won the Golden Peacock Award for his epoch-making Gamperaliya, (The changing village) his personal triumph came to be thought of as an honour endowed on Sri Lanka by India.

For most of those who talk about the fortunes of Sri Lankan cinema, the characterization of the sixties, as the Golden Age of Sinhala Cinema, seems an utterly acceptable reflection of reality. Sri Lankan cinema was very much alive during this specific period of time. Highly praiseworthy achievements in the fields of directing, acting, and technical expertise, acquired a classic glow.

At this stage in the evolution of Sri Lankan cinema, one cannot, in any way, overlook the substantial contribution made by foreign embassies, here in Sri Lanka.

A few could be referred to. An extremely helpful Retrospective of Short Films from the Oberhausen Festival in Germany was held here, with the participation of an extensive group of Sri Lankan enthusiasts. (Incidentally, I had the honour to preside over this session and many other events of this calibre).

At this stage I cannot help but mention a personality, who contributed much towards Sri Lankan film culture, with selfless dedication and devotion. The person I refer to is the late Neil J Perera, who deemed it his personal mission as it were to serve the cause of cinema enlightenment in our land. Most of those foreign embassy film events were organised by him, including the above mentioned Oberhausen Retrospective.

Incidentally, he enabled my Junior University students to meet well-known film critic and historian Roger Manvell.

Mass Communication

I refrain from touching on my personal contribution to the progress of cinema culture in our country, because even a slight, stray fact is likely to assume the proportion of hyperbole.

But, some aspects are essential to be looked at for reasons of history. In 1969, at the Junior University of Dehiwela, I introduced the study of Mass Communication to Tertiary education in the country.

It was here that Cinema and associated disciplines were taught for the first time at higher education level. I assiduously translated material related to cinema and allied subjects, into Sinhala. This made me, by history, the pioneer in teaching Cinema in Sinhala at Tertiary education level. I did not stop there. I made my students ‘experience’ certain areas of cinema culture. I took them to participate in the ‘Premiere’ of a film at a public cinema. Director Amaranath Jayatileke provided this opportunity.

I took them to observe the manner in which a film festival is organised.

All this is central to the current situation of cinema in Sri Lanka.

I was quite moved and impressed no end, when the present Minister of Culture, Sajith Premadasa stressed with marked emphasis, that he will ensure that the glory of Sri Lankan Cinema will be upheld through proper provisions and policies.

I disciplined my students, at the Junior University level with the future very much in mind. We may lavish our best resources to renovate our cinemas, equipping them with the most advanced digital systems.

The projection will be state-of-the-art. When we have such advanced cinemas if audiences thronged only to view non-Sri Lankan films, it would be vastly pathetic.

I esteem the effort to train our younger generation to become loyal and committed filmgoers, extending their patronage to indigenous films.

Our top-priority requirement is to bring into being a loyal audience, who will enthusiastically encourage the development of indigenous films by their patronage. We must introduce to the educational syllabus of this land, the teaching of film appreciation as an academic subject of pragmatic significance. The emergence of a sophisticated audience for their film, which in turn, awaken the filmmakers to create classics, for which our noble country will prove to be a most valuable and unceasing source and fountain.

Sri Lanka’s annual cinema output does not seem to increase in a striking style. Even in such an environment, our film-potential bursts into glory with an astoundingly outstanding work of high appeal.

In the recent past, there have been some massive (epic, if you like) cinematic offerings. Director Jackson Anthony’s ABA is undoubtedly in that category. Director Saman Weeraman and Producer Navin Gooneratne, presented to the world the spiritual odyssey Siddhartha Gauthama, for the serene joy and emotion of the people everywhere in the world.

Viewed this way, our most urgent need is to begin the training of the young generation of ‘devotees’ to inherit the responsibility of protecting our sacred indigenous film culture.

We in Sri Lanka can be proud of an elitist group of Directors, actors, actresses and technical experts. We are faced with the formidable task of unifying that multiple expertise, into a renewed, and rejuvenated Sri Lankan cinema culture.

Protected, patronised and blessed by a highly reputed Minister, who is dedicated to getting things done, a truly Golden Era for Sri Lankan cinema is not only a beautiful dream, but a highly practical and brilliantly realizable goal.