In anticipation of Wednesday’s parliamentary debate on the Bill to establish an Office of Reparations, civil society groups and activists have voiced concerns that as it stands, the legislation could create an office that is weak and dysfunctional.

Chairman of the Office on Missing Persons (OMP), Saliya Peiris has hope for the Bill, “if the office is implemented in the spirit in which the law is being introduced,” but others are urging parliament to amend the Bill, fearing even if it is implemented, the office will be too dependent on the Government to function properly.

The Reparations Bill is the second pillar in a four-pillar transitional justice scheme the Government first proposed to implement at the UN in Geneva in 2015 as part of a process of reckoning with the country’s violent past.

Despite these high hopes, some activists and researchers believe the office, as described in the Bill, could be beholden to politics. The Centre for Policy Alternatives (CPA) released a statement on Thursday (4) arguing that the current Bill, “will likely lead to a situation of political bargaining, trade-offs and politicisation that will eventually undermine the integrity of reparations.”

Senior researcher at CPA, Bhavani Fonseka told the Sunday Observer: “If the office is so dependent on legislature, everything else in the office is moot because they cannot do anything.”

Activists point to shortcomings in the draft legislation that will not give the Office of Reparations real decision- making power, and limit its investigative capacity.

While the proposed office will be able to provide recommendations to other government agencies, according to Clause 11(1)(g), those recommendations will first need to be presented to the Cabinet of Ministers. Then, before the actual reparations are dispersed—whether it is a cheque for a widow or a certificate of absence—they must be presented to and approved by Parliament. As a result, MPs or cabinet members could delay the process or refuse reparations to victims and their families.

Ruki Fernando, an outspoken activist who has worked closely with families of the disappeared, said this will unnecessarily politicise the reconciliation process.“The whole idea of the independent institution is that it is going to be staffed by people who are professional and seen as separate from politics,” he said. “Politicians are neither competent nor impartial enough to deal with a sensitive topic like reparations.”

But legal experts strongly argued that Article 148 of the Constitution guarantees that Parliament shall have full control over public finance and while the proposed Office of Reparations will be an independent policy making body, the policy it makes will have huge monetary implications which will have to be borne by the tax-payer.

“The clauses being objected to are in the bill for practical and constitutional reasons. If Parliament does not allocate funds where will the money come from?” asked one expert speaking to Sunday Observer confidentially. The Office of Reparations must work within the parameters of the constitution and if not for the safeguards worked into the bill, which allows Cabinet and Parliament to approve policy recommended by the independent office, the Supreme Court would have shot down the draft legislation when it was challenged before the debate, the legal expert added.

Chairman of the OMP, Peiris agrees, saying Government involvement is a necessary component of these institutions.

“Offices such as the OMP or Reparations are the responsibility of the State and they should be funded by the State primarily,” he said. “Unfortunately in operationalising these independent institutions, there are sometimes administrative hurdles which stand in the way.”

However, with the Reparations Office, the politicisation of the process could prove to be more than just a “hurdle”, legal experts say.

President of the Families of the Disappeared, Britto Fernando said he fears politicians will be able to recommend reparations to their supporters, citing the history of Samurdhi allocations, which have been criticised for being distributed politically, as an example. Because a diverse group of government agencies will be involved in distributing reparations-- from the military releasing land to the Ministry of Women and Child Affairs handling education issues-- Ruki Fernando says, in order to streamline the process, the Office on Reparations must have legal power to direct these agencies to implement policies.

For Fonseka and CPA, the independence of the office is the most crucial concern, upon which its very functionality depends. And because funding will need to be approved by parliament, she believes revisiting parliament is an unnecessary bureaucratic step.

But the Office will not be mandated to seek Parliamentary and cabinet approval for each allocation, as some reports indicate, the legal expert responded. Approval will only be sought for the overarching policy pertaining to the granting of reparations – either monetarily or by other means. Acknowledging that Parliament and Cabinet could shoot down some of the recommendations made by the Office, the expert said that this will have to be done through a process of debate, which will be public. “This is the system we have, and Parliament is the institution that controls the public purse,” the expert explained.

“We can’t say Parliament shall have full control over public finance when it’s a project we don’t like, and argue the opposite when it’s an Office we want,” the legal expert pointed out referring to some civil society objections to the Bill.

The Tamil National Alliance is likely to vote for the bill to establish the Office of Reparations and there were no plans to move amendments in Committee stage so far, TNA Jaffna District Legislator M.A. Sumanthiran told Sunday Observer.

The draft legislation to set up the Office of Reparations is unlikely to get the support of the Joint Opposition, which backs former President Mahinda Rajapaksa. It could however win the support of the JVP which also voted in support of legislation to establish the OMP.

Britto Fernando says the biggest challenge the office on reparations will face is gaining the trust of victims. “Tamil victim families are losing faith in the Government.

They fear the Government isn’t going to do anything but is just showing internationally that they are doing something,” he said.

The Office of Missing Persons was the first of the ‘pillars’ to be established, with legislation to set up the permanent office to trace, investigate and recommend compensation for victims of enforced disappearances and their families passed in August 2016.

The Office was finally set up in February this year. If enacted this week, the Office of Reparations will be the second official mechanism to be set up to deal with lingering post-war issues.

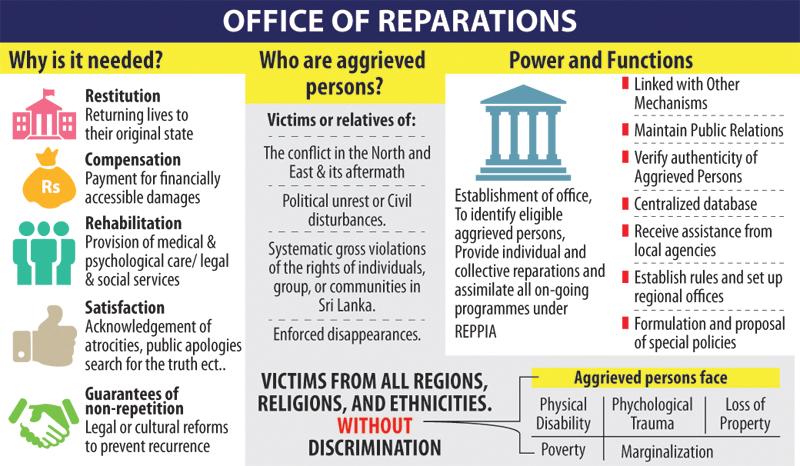

Graphic : Manoj Nishantha