Historically speaking,wealth and piety had been the two legitimisers of Muslim leadership in this country. Wealth came from two sources, inheritance and trade. Of the two, trade is closely linked with the origin of Islam. For instance, the Prophet himself was a trader, his first wife Khadija was one of the wealthiest trading magnates in Mecca, and so were a few of the Prophet’s closest friends and followers. The Quran itself uses commercial terminologies as metaphors to impart its messages. It is therefore not outlandish to claim that trade is the most representative profession of Islam.

It is also not a coincidence that Islam was introduced to this island through traders, originally from Arabia and subsequently from India. The Muslim community started as a trading community and remained so until recent times, although one section took to agriculture after the 16th century. It was this commitment for trade and business that earned the community the colonial sobriquet “business community”. Hence, it was natural that Muslim leaders in the past came mostly from wealthy business families.

Piety as a legitimiser of leadership claim played its role in an indirect way. Not all wealthy are pious and not all pious are wealthy. Piety is entirely a matter between a believer and the Creator and there is no standard measure of assessing whether one is genuinely pious or not.

However, in the eyes of ordinary Muslims a person’s piety could be gauged by that person’s commitment to the five pillars of Islam, namely, faith, daily prayers, fasting during Ramadan, paying Zakat and pilgrimage to Mecca.

The last of these automatically bestows the title Haji, which adds to the person’s respectability in the community. Commitment to these religious obligations certify one as a practising Muslim.

In addition, it is the extent of one’s attachment to the mosque in one’s locality, particularly, the involvement in administering the affairs of the mosque, such as, taking care of the building and other facilities, and looking after the welfare of mosque functionaries such as, imams and muezzins that really enhance a person’s leadership claim. Long before the Wakfs Board was established in 1956, it was private individuals and families that administered and governed the mosques. Leading business families invariably became caretakers of mosques.

Open demonstration of piety won the admiration of the ulama, whose opinion carried decisive weight among ordinary Muslims. Long before S. W. R. D Bandaranaike discovered the political importance of Buddhist monks for his 1956 election campaign, Muslim leaders realised the crucial value of the ulamaas opinion makers in the community. The ulama,because of their monopoly over religious knowledge automatically won the respect of the Muslim masses.

A few of the ulama were also engaged in businesses but many were attached to mosques and madrasas and at least partly depended for their income on the generosity of the worshippers. Since wealthy business families took care of the maintenance of mosques and the running of madrasas linked to these mosques the ulama became closely attached to those families. While the ulama provided religious leadership, leading businessmen provided leadership over mundane matters.

This businessmen-ulama combination was the base from which early generations of political leaders emerged in the Muslim community. To this class of leaders, politics was primarily a mechanism not to advocate policies and principles to benefit the nation but to achieve favours and concessions to themselves and their community.

Party politics that developed over the years provided ample opportunity to these leaders to demonstrate their bargaining business skills. Their behaviour in Parliament was driven more by short term sectional interests than long term national interests.

For instance, when the Ceylon Citizenship Act of 1948 and the subsequent Indian and Pakistani Residents (Citizenship) Act of 1949 were introduced in Parliament, Muslim leaders supported both, partly because repatriation of Indian and Pakistani businessmen would mean less competition to local Muslim businesses.

Similarly, when the National Language issue came up in the 1950s Muslim parliamentarians unanimously opted for Sinhalese, as it was the language of their business customers, despite Tamil being the mother tongue of the majority of Muslims.

What was lacking in this leadership was the presence of a secular intellectual class. There were a few legal professionals but not an educated class as such.

The Muslims’ delayed entry to secular education was the main reason for this absence.

It was not until after the 1960s in general, and after the 1990s in particular, that one sees the emergence of a secularly educated elite among Muslims.

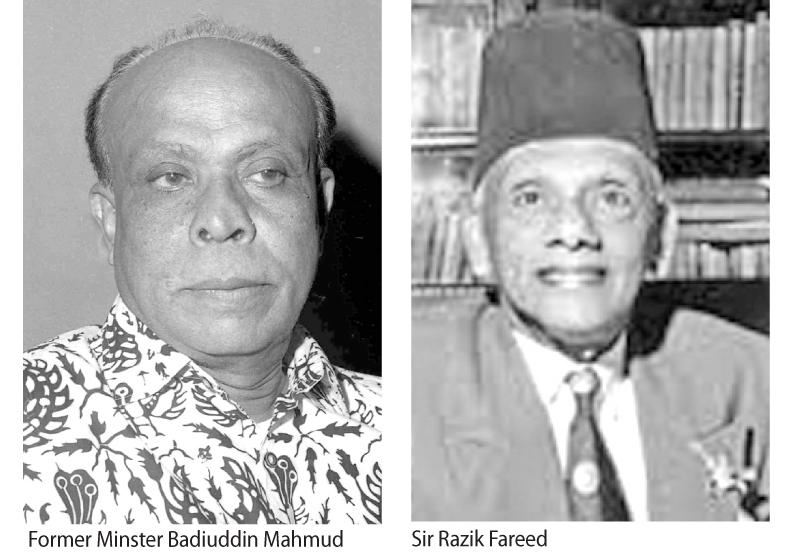

In this respect, one should remember the role of a charismatic Muslim leader, Badiuddin Mahmud, popularly known as Badi. He was the first Muslim professional educationist to hold a Cabinet position.

Badi, a product of Aligarh University, in India, and a contemporary of Muhammad Ali Jinnah, the father of Pakistan, was the Minister of Health from 1960 to 1963 and then Minister of Education from 1970 to 1977, both in the Srimavo Bandaranaike Cabinet. Before becoming a Minister he was the Principal of Zahira College, Gampola.

During his second tenure as Minister he held a crucial meeting at his Colombo residence, in 1972, and invited a number of his community leaders. He had a simple message to them, to change the direction of the community from business to other pursuits if the community was to thrive under a socialist Bandaranaike government.

He despised the colonial sobriquet ‘business community’ attached to the Muslims. It was as part of that change of direction that he used his Ministry as a vehicle to improve the educational standards of Muslim students.

Even when he was the Minister of Health he worked closely with the then Minister of Education, W. Dahanayake, and it was during Dahanayake’s Ministry that Government Tamil Schools with more than 50% Muslim children were declared as Government Muslim Schools.

Actually, it was the culmination of an agitation started in the early 1950s by another Muslim leader, Razik Fareed. Under Badi however, a number of such schools were raised to the status of High Schools or Muslim Maha Vidyalyas staffed by Muslim trained teachers. To produce more trained teachers he opened two additional Muslim Teachers’ Training Colleges, for men and women, respectively.

Hence, due to the changes introduced during this period, particularly to university entrance criteria, the number of Muslim students seeking higher education increased after the 1980s.

The present generation of Muslim scholars and professionals in the country, and the current crop of Muslim politicians, are indeed indebted to what could be termed as the Badi Revolution.

Badiuddin was also instrumental in founding the Islamic Socialist Front, a Muslim political wing attached to the Sri Lanka Freedom Party of which he was a founder member.

Although Badi’s efforts provided great impetus to secular learning in the community and was responsible in creating a class of Muslim educationists and professionals, his measures did not change the structure and nature of religious education. The number of moulavi teachers in state schools increased but the curriculum of the madrasas was left totally untouched.

Although the ulama of today are more articulate and better organised than their predecessors, yet, they remain even more conservative than before, in matters affecting the community. The All Ceylon Jamiyyathul Ulama (ACJU),the apex body of ulama, is heavily influenced by ultra-orthodox ideologies and its leadership has also the backing of leading Muslim businessmen.

What this means is that the new class of politicians even though more secularly educated, cannot function as effective leaders without the support of the ulama, ACJU and the business sector. The prevailing impasse in reforming the Muslim Marriage and Divorce Act (MMDA) reflects this ineffectiveness. This is one part of the tragedy of Muslim political leadership.

The other part is systemic in that, it emanates from the state of the prevailing national political environment, which is coloured by ethnocentrism, corruption, nepotism and cronyism. The present generation of Muslim politicians reflect all the characteristics of the national malaise.

Their predecessors were at least able to apply their bargaining skill to reap benefits to the community but the new generation bargains for personal benefits and positions. They behave like petty sultans and nabobs in their respective constituencies with cronies to guard them, and a few are dangerously playing with the ethnic fire which will ultimately consume pockets of Muslim enclaves. Muslim political leadership is thus trapped between religious conservatism and political myopia.

As a result, Muslim businesses, mosques, and madrasas are facing an existential crisis. Is there a way out of this trap?

The solution has to start at national level. Unless there is a systemic change the descent to kleptocracy and kakistocracy is guaranteed. The country is desperately in need of a radical change in political leadership. The old guards waiting in the wing are as corrupt and policy bankrupt as the ruling ones.

The sixth estate has to rise to the occasion. The small Muslim segment of this sixth estate is remaining silent as a counterpart among the Sinhalese and Tamils.

Unless this segment speaks out openly and bravely, and captures the hearts and minds of young voters there seems to be no redemption to the community from the grips of a conservative religious hierocracy and a corrupt political leadership.

[The writer is a professor at the School of Business and Governance, Murdoch University, Western Australia]