Sri Lanka had a comprehensive law on poll campaign financing until the 1978 Constitution which uprooted this piece of important legislation in toto. The law had authority to unseat elected public representatives and even withhold their civic rights for years, preventing offenders from running for public office.

The ‘Order in Council’ of September 1946, mandated the candidates, all elected and non-elected to submit a Financial Statement covering even the trivial expenses paid as interpreting and translation fees, within a month’s time of election day.

At the 1947 Kandy by-election, T.B. Ilangaratne and George E. de Silva, the first Cabinet Minister of Industries, were rival candidates. Illangaratne emerged the loser at the election. He later filed an election petition saying his defeat was masterminded by his opponent who launched a malicious campaign of misinformation. Ilangaratne lost his job after the 1947 General Strike but an article published in the run up to the election claimed he was sacked for bribery. The article was written by a Buddhist monk and Ilangaratne proved the monk was one of George R. de Silva’s campaign agents by submitting evidence of the Monk’s speeches made at the rallies.

Later, George E de Silva was stripped of his seat as well as of his civic rights for seven years.

At the Kandy by-election the next year, Ilangaratne faced George E de Silva’s son Fred de Silva, former Kandy Mayor. This time Ilangaratne emerged the winner but Fred de Silva too filed a petition over false propaganda and he too won the case. Ilangaratne was unseated and stripped of his civic rights for seven years. (Since he was unable to contest, his wife Thamara Kumari Illangaratne nee Aludeniya contested the next by-election and was elected to Parliament.)

Later, a petition was also filed against Fred de Silva citing campaign financing laws. During the campaign period Fred de Silva used the services of a Tamil translator. The fee paid to the translator was Rs.25. In the financial statement he overlooked to mention this seemingly trivial expense. For this omission, Fred de Silva lost civic rights for three years, despite the fact that he was not among the elected members. So tough was the law on campaign financing at the time. The Supreme Court had the powers to hear election petitions on campaign financing.

In 1965, P.B.Dedigama was also charged under the campaign financing law. He was given nomination to contest the election against Dudley Senanayake in the Dedigama seat. Subsequently, he abandoned his own campaign and offered support to Dudley Senanayake. This was announced in a newspaper advertisement. Since he did not contest the election, Dedigama did not submit the financial statement mandatory for every candidate. But in a subsequent petition filed in the Supreme Court he was found guilty of the said offence and fined.

PAFFREL Executive Director Rohana Hettiarachchi said ‘unchecked campaign financing is evil in a sense that it distorts people’s free will, depriving a level playing ground for candidates while opening flood gates to a free flow of black money.’

“It even converts the politicians into slaves of their financiers instead of representatives of the people who voted them in,” he said emphasising the need to bring in regulations.

Following the revelations made by MP Dayasiri Jayasekera, and subsequent CID revelations in Court about State Minister Sujeewa Senasinghe, of how stupendous amounts of money was infused into campaigns by Arjun Aloysius, a crafty businessman who is now under arrest for swindling EPF (Employees Provident Fund) money through a Treasury Bond scam, the public outcry for stringent campaign financing laws has become more vigorous.

Jayasekera stirred up a hornet’s nest when he declared recently that he accepted Rs.1 million from Aloysius for the 2015 election but no law in this country found him guilty of any crime. Last week, Senasinghe was named in the CID B report to court as having received cheques to the tune of Rs 3 million from W.M. Mendis, a company connected to Perpetual Treasuries. On camera, Minister Sarath Fonseka also admitted his campaign had received Rs. 100,000 in financing from Aloysius. But it is claimed that the actual list of Parliamentarians who were financed by Aloysius is a shocking number, not counting media persons and government servants.

The Election Commission (EC) is in fact working double time to bring in the laws on polls campaign financing as soon as possible. A cabinet paper to this end was given approval with the Cabinet of Ministers agreeing in principle that laws should be brought in to regulate this sector.

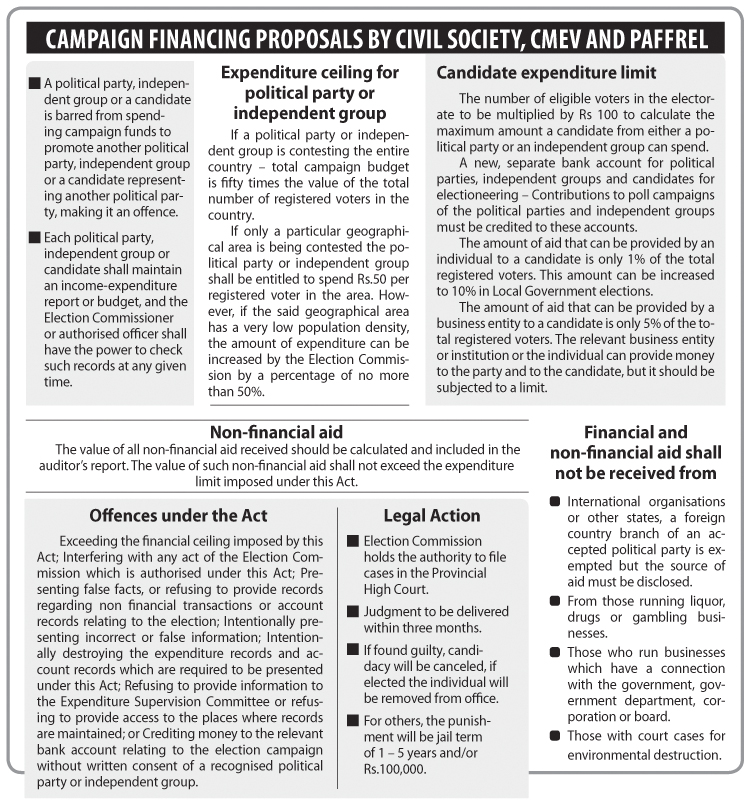

The EC proposals require the political parties and independent groups to submit an audited Financial Statement within two months of the release of election results. While it incorporates provisions to bare the funding sources, the proposed law has not spelt out stringent penalties for the offenders, other than depriving the candidate of his seat, if elected. In contrast, the polls observers have come out with a draft containing proposals for a comprehensive campaign finance law with rather harsh penalties that would definitely deter wrong-doers.

However a Legal Expert at the EC said, “Already there are punitive provisions in the existing elections law. Therefore, once the new law is in place the old provisions can also be revived to mete out punishment to the offenders.”

Under the Elections Act, illegal campaigning involves a Rs.500 penalty and the scrapping of civic rights of the offender for three years. It applies to not only a candidate but even an ordinary party supporter. If a candidate is found guilty of an offense under campaign finance laws a case can be filed in the Courts and the person can be deprived of civic rights, yet there is a big question mark if the punitive provisions in the law are strong enough to discourage the offenders given how appetising the money that is funnelled into their coffers during electioneering can be.

The draft law prepared by EC to regulate ‘unlimited and undisclosed’ cash in elections, in all three languages, is currently with the Attorney General’s Department, for fine tuning before it goes to the Legal Draftsman and then the Parliament for ratification if things go according to plan.

“Until it is passed, we cannot be sure if this particular piece of law will be supported by the legislators, as it is a highly favoured mode of campaign financing,” a senior EC official said.

But the polls observers are not happy about the way it has been hastily prepared. “Although we cannot complain about the commendable effort to reign in election funding which certainly highjacks people’s conscience, I must say that we haven’t set our eyes on this draft law so far,” Manjula Gajanayake of the Centre for Monitoring Election Violence (CMEV), a leading local Polls Observer said.

“Although some quarters of society might opt to disagree, we believe for a new law to be most effective, it has to go through an exhaustive consultation process. I am not sure whether the proposed campaign fiancé law by the Commission has had the opportunity to be reviewed by the stake holders.”

Their crying foul here is not without logic. In the US, where they say the best money-in politics regulatory regime exists, the defenders grapple to cement the loopholes exploited by politicians as well as unscrupulous businesses, going to the extent of fighting financing restrictions in their highest court.

In 2014, the US Supreme Court struck down caps on the total amount individuals can donate to federal campaigns and political parties saying the law violated free speech protections.

****

India’s Campaign Financing Law

Submission of Accounts

Under section 77 of the Representation of Peoples Act 1951, every candidate at an election to the House of the People or State Legislative Assembly is required to maintain a separate and correct account of all expenditure between the date on which he has been nominated and the date of declaration of result, both dates inclusive.

Every candidate has to lodge a true copy of the said account within 30 days of the release of election result.

Buying of votes with cash banned totally

Since buying of votes is a major problem, the Indian Election Commission had banned transport of cash in large quantities during the election campaign period.

Today, India’s political finance regime is plagued by three major flaws:

There is a steady torrent of undocumented cash to both parties and candidates.

The Association for Democratic Reforms found that nearly 70% of party funding over an 11-year period came from unknown sources. Such funding amounted to nearly Rs.7,900 crores in 2015-2016. Political parties can hide the source of contributions above Rs.20,000 if they are in the form of “electoral bonds”.

There is virtually no transparency regarding political contributions. Often the identities of both the giver and the receiver are not known.

Political parties are not subject to any form of independent audit, which renders their stated accounts both fictional and farcical.