Moving away from my preoccupation of writing on literature and films, I will now review a book of a political nature.

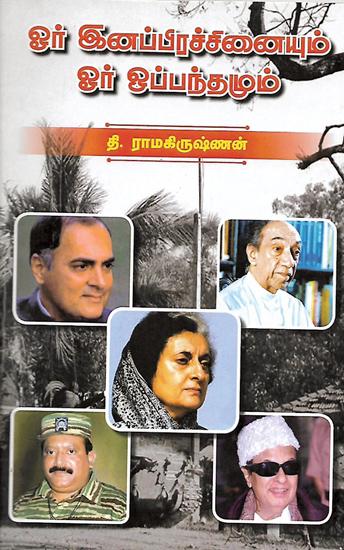

The book is in Tamil and written by an eminent journalist, Thiyagarajan Ramakrishnan, from The Hindu in Tamil Nadu. He is one of the sons of the late, illustrious bilingual writer popularly known as, Asokamitran. The book is titled Or Inap Pirachanaiyum Or Oppanthamum meaning An Ethnic Problem and AnAgreement.

He writes about the Indo -Lanka Agreement- signed between the two governments of India and Sri Lanka on July 29, 1987.

According to the writer, there is still the problem of amalgamating the two Provinces of the North and the East but the Indian government will not pressurize Sri Lanka on this issue. There is also the issue of abolishing the Provincial Council system.

The writer says, he is trying to see whether the above agreement was a real failure. He wishes to debate on the political consequences arising from the Agreement.

I am not going to recount everything the writer has written about the events that took place before and after the signing of the Agreement partly because it is history and it is not relevant for me to explain the purpose of his writing for his book at this juncture. The writer narrates the happening as facts and there is no doubt about that. Here is an occasion for Indian readers to know something they may not have been aware of.

However, it is interesting to note some information on the Indian Peace Keeping Force (IPKF). As a Tamil I felt sad when the people living in the North and East of Lanka under the occupation of the Indian armed forces were undergoing misery as those Jawans could not speak Tamil and there was a communication problem there. The Jawans came from the 54th mountainous region of the Army, headquartered in Telugu, speaking Hyderabad, we understand.

Had the majority of the forces been empathetic towards the people and attacked only the militants, the Agreement would have made the country less violent.

On page 51, Ramakrishnan points out that the then Indian High Commissioner, Dixit, was taking a strong stance to continue with military action while senior authorities in the Indian Army had their own views.

“Within two weeks the IPKF lost 153 of their personnel and that includes 12 senior high-ranking officers…. Nearly 21 doctors and nurses were killed by the IPKF “

The writer says, it was a historical error (Kolam) that Mr. Ranasinghe Premadasa stringently opposed the Agreement. (Page 59).

Another question thewriter asks is, whether either the IPKF or the Indian government was attempting to draw the Tigers via the EROS group. The writer then narrates the relationship between the various militant movements in Sri Lanka and the Indian government.

Dixit was in Sri Lanka for four years until 1989, and then transferred to Pakistan. His period of reign was most challenging and was a hard experience in Indo-Lanka relationship says Ramakrishnan. He also says, he was not fully responsible for all the mistakes that were made. The Indian government realized belatedly that the purpose of sending the IPKF was not achieved.

The book narrates what happened in contemporary Lankan history during and after the presence of the IPKF on Lankan soil. The IPKF stayed here for 32 months until March 24, 1990.

Ramakrishnan says, some believe, the Indo-Lanka Accord had come to an end but the 13th Amendment is there in the Sri Lankan Constitution.

The writer believes, the 13th Amendment, despite some loopholes is the best political solution for the Tamil people in Lanka.

The DMK leader M Karunanithi is reported to have said that the IPKF has killed 5,000 Tamils and therefore, he would not attend a function to receive the returning IPKF personnel.

On page 84, Ramakrishnan says, in attempts to make permanent peace in the North-East region on many occasions, both, the Tigers and the Sri Lankan government missed the opportunities.

The merging of the North and the East Provinces is no longer valid according to the order of the Supreme Court given in 2006.

On page 106, the writer states clearly that the Tamil Nadu factor was as important as the global situation as far as the Indo-Lankan agreement was concerned. After the assassination of the former Indian Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi, the Indian government banned the Tigers on May 14, 1998. This ban still continues. It is painful that the Indian PM was killed by the Tigers, Ramakrishnan says. He reminds that Dixit had said India was against the formation of Tamil Eelam.

The writer believes, the Rajiv Gandhi Government entered into an agreement with the J R Jayewardene government because Tamilnaadu should not be affected by the influx of extreme elements into it. (Page 115 bottom)

To the question whether the Agreement was successful or not, the writer argues that the Indian government was not thinking of crushing the Tigers altogether but wanted to weaken them and make them act according to the government’s decisions. There was no clear thinking in the Indian government as far as the operation of the IPKF in Lanka was concerned.

Ramakrishnan says, when one examines the Agreement, only the military activities were highlighted but not the deep impact of the 13th Amendment. In Sri Lanka, there is an opinion that the 13th Amendment was forcibly introduced. The writer strongly believes the 13th Amendment stands as a permanent witness for the Agreement between the two countries. It is meaningful even today, he contends.

What is fundamental to solve the ethnic problem in Lanka is to realize that the country is a society of multiplicities. It is by the Agreement that the country became a unified state, the Agreement is not a failure and it is valid even now, according to the author.

Finally, in his long chapter on the subject of whether the ethnic problem could be solved, Ramakrishnan concludes his book. The main points he stresses are: In other countries ethnic problems have been successfully solved; The 1972 Constitution worsened the problem; Tamil Eelam is not practical.

He points out four items that should be made practicable:

* Widows who lost their spouses in the war should be rehabilitated and helped

* Return of lands occupied by the Lankan forces should be expedited

* Innocent prisoners should be released

* Lankan refugees in Tamilnaadu who wish to come back to the country should be assisted.

The book has several photographs, bibliography and datelines of Lankan contemporary history.

This book in my opinion should be read by all the young people born after 1980 to understand the political history of the island nation. A Sinhala translation could help give a wider audience to the book. The writer’s arguments are reasonable from my point of view, although the writer vigorously defends his country’s stance on the Indo-Lanka Agreement.

All Tamil speaking politicians in India and Sri Lanka should read this book.