When I visited Negombo, more than ten years ago, I passed by some of Colombo’s poorer areas, where people lived in wooden shacks, in densely packed informal settlements, along the Dutch Canal (Hamilton Canal) with fishing boats moored along much of its length. But, during my recent visit to Negombo, I glimpse a completely different image. New highways and new housing settlements dotted the Negombo road. The canal has got a face-lift. However, the fisher folk are active in the Negombo lagoon as they have always been, for hundreds of years.

When I visited Negombo, more than ten years ago, I passed by some of Colombo’s poorer areas, where people lived in wooden shacks, in densely packed informal settlements, along the Dutch Canal (Hamilton Canal) with fishing boats moored along much of its length. But, during my recent visit to Negombo, I glimpse a completely different image. New highways and new housing settlements dotted the Negombo road. The canal has got a face-lift. However, the fisher folk are active in the Negombo lagoon as they have always been, for hundreds of years.

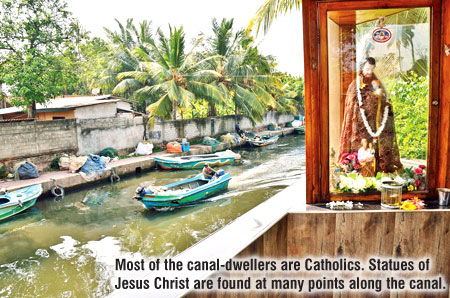

Between Colombo and Negombo, the legacy of the Portuguese is evident in the large Roman Catholic population. I saw evidence of this in the numerous Roman Catholic Churches we passed, along the way, as well as in the many dozens of elaborate nativity scenes of large statues of Jesus Christ and Virgin Mary, outside not only churches, but at many junctions.

The Portuguese were the first outsiders to establish a base here. In the 1600s they lost it to the Dutch, for whom this area became an important source of cinnamon and cloves. As the Dutch East India Company (VOC) faded from the scene at the end of the 18th century, the British arrived, taking over the town in 1796.

‘Spice Island’

My visit to Negombo was to capture its colonial legacy and I decided to explore and photograph the Hamilton Canal’s historic importance in the country’s past, and how it fits into Sri Lanka’s long and foreign dominated reign, as the ‘Spice Island’.

The old 19th century Dutch canal (Hamilton Canal) runs from the north bank of Kelani Ganga, where it enters the sea at Hendala, a little to the north of Colombo, to the southern tip of the Negombo lagoon, and then winds through the middle of the town, and to its northern end at Puttalam, more than 120 kilometres away.

The history of the canal network goes back to the reign of King Veera Parakramabahu VIII (1477-1496) who ruled the Kingdom of Kotte. It is said that the King constructed the canal connecting outlying villages with Colombo and the Negombo Lagoon, to ease the transport of spices and most important of all, cinnamon, to the Kingdom’s main ports.

The history of the canal network goes back to the reign of King Veera Parakramabahu VIII (1477-1496) who ruled the Kingdom of Kotte. It is said that the King constructed the canal connecting outlying villages with Colombo and the Negombo Lagoon, to ease the transport of spices and most important of all, cinnamon, to the Kingdom’s main ports.

The Portuguese constructed the original canal in the 17th century, but it was the traders from the Dutch East India Company who expanded the canal, in the next century. The Dutch settlers also used the canal to transport pearls and spices from the north to Colombo.

The Dutch were displaced by the British. Between 1802 and 1804, when the island was under British rule, a new Colombo- Negombo canal was built and commissioned. It was named, the Hamilton Canal in 1804, after the well-known English civil servant Garvin Hamilton, who was based in Colombo. Hamilton Canal ran west of the Old Dutch Canal, quite close to the sea, from the mouth of the Kelani Ganga at Hekitta to the southern edge of the Negombo Lagoon at Pamunugama, a distance of 21.5 kilometres.

Water world

Exploring the great canal, I first visited Elakanda, where the Hamilton Canal begins and runs west of the Old Dutch Canal towards the Negombo Lagoon. Entering the canal from the estuary of the Kelani Ganga, revealed a very different water-world. The mouth is wide, dominated on the right bank by a huge banyan tree and an imposing bronze statue of Jesus Christ, a reminder that this area is populated by many Roman Catholic fisher folk. Today, the chip-tile laden canal bank is used to moor colourful fiberglass and wooden fishing boats that go to sea via the Kelani Ganga. The fish stalls are heavily laden with the night’s catch, and the canal-side is busy with buses and trishaws.

The renovation of the canal has been executed in lengths of around three kilometres in Elakanda. A beautiful eye-catching castle and the suspension bridge for pedestrians is located within a short distance from the entrance to the canal. A small park in the bank of the canal comprises walkways shaded by newly planted saplings, giving ample space for travellers to relax.

About six kilometres up, the Hamilton Canal reaches the Muthurajawela marsh, a paradise of tall grasses and pollarded trees, with white flowers, birds, fish and butterflies, and also, the occasional crocodiles and pythons. Soon, the Mudiyansage Ela is encountered, which flows inland and connects with the Hamilton Canal. This is where one needs a boat to explore the short stretches of marsh between canal and sea, since it is located on a beautiful and lush section of the Canal, just before it empties into the Negombo Lagoon.

About six kilometres up, the Hamilton Canal reaches the Muthurajawela marsh, a paradise of tall grasses and pollarded trees, with white flowers, birds, fish and butterflies, and also, the occasional crocodiles and pythons. Soon, the Mudiyansage Ela is encountered, which flows inland and connects with the Hamilton Canal. This is where one needs a boat to explore the short stretches of marsh between canal and sea, since it is located on a beautiful and lush section of the Canal, just before it empties into the Negombo Lagoon.

The one and a half hour boat ride takes one along the Hamilton Canal, through the marsh onto the lagoon. Along the way one is able to click images of water bodies and mammals. Exploring the vast expanse of Muthurajawela to the East would be an expedition in its own right. Peace and tranquility reign in the narrow waterway and sluice gates.

Along the next uninhabited stretch one comes across a black pedestrian bridge behind which lurks a stone cross. Look up to your right and you may glimpse the high, silver, neoclassical dome of St. Joseph’s Church, at Pamunugama. It is only a couple of metres from the Hamilton Canal.

From Pamunugama, the Hamilton Canal reaches the Negombo lagoon. The mouth of the canal is flanked by marsh scrubs. Coming to Negombo town, I explored the nine-kilometre stretch to Maha Oya, which was rehabilitated with chip-tile laden broad pavements, beside the canal.

At the north end of the lagoon, right in the middle of town, the Hamilton Canal continues north. At its entrance in Negombo, it is much smaller, shallower and congested with small fishing boats with just enough room for the boats to pass each other. After about five kilometres it empties into the Maha Oya, which is a fresh water lagoon adjoining the Indian Ocean. After a detour of several metres down the Maha Oya, you enter the Hamilton Canal once more.

At the north end of the lagoon, right in the middle of town, the Hamilton Canal continues north. At its entrance in Negombo, it is much smaller, shallower and congested with small fishing boats with just enough room for the boats to pass each other. After about five kilometres it empties into the Maha Oya, which is a fresh water lagoon adjoining the Indian Ocean. After a detour of several metres down the Maha Oya, you enter the Hamilton Canal once more.

Along the rehabilitated stretch, I observed the life of the community. Many of the fisher folk and other villagers along the canal are Roman Catholics who trace their faith back to the Portuguese colonial era. After selling the day’s catch to the ‘Lellama’ fish market in the wee hours of the morning, the fisher folk return and moor the boats alongside the canal. They then work on their boats and mend nets, sitting on the pavement of the canal during day time.

Although the Hamilton Canal was developed reinforcing both sides with stonework and chip-tile laden broad pavements, its water is still highly polluted. One of the vendors who runs a tea boutique on the bank of the canal told me, they used to bathe in the canal  more than ten years ago. Today, not even a boy wades through the canal due to the pollution caused by all the sewage lines from nearby houses, which point directly into the canal.

more than ten years ago. Today, not even a boy wades through the canal due to the pollution caused by all the sewage lines from nearby houses, which point directly into the canal.

A old spice

There are a cluster of small concrete bridges over the canal which the inhabitants pass, and where ferries once prevailed. They have been repaired and I witnessed cyclists carrying their bicycles across the canal, climbing the flight of steps of the bridges to cross to the other end. Occasionally, I passed several boats filled with tourists returning from the Maha Oya, through the Hamilton Canal.

The potential for tourism is enormous, as the Canal has been developed to make it a scenic attraction for tourists. It is the perfect venue for the tourist who wants a little adventure and at the same time experience the beauty and history of the colonial settlers’ ancient spice trade. The tour will no doubt add a little ‘spice’ to the modern tourist’s agenda.