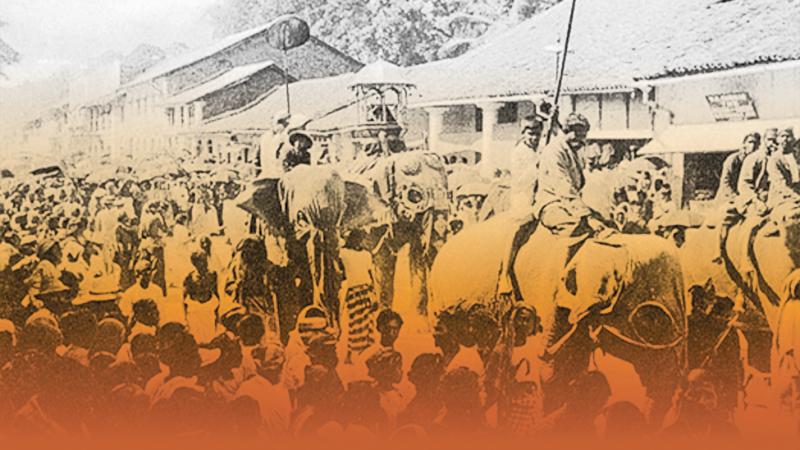

Perahera, known as procession in English, has fascinated many people ever since its inception. Some of the most notable figures who have been captivated by this ancient Sri Lankan tradition include the Chinese Buddhist bhikkhu Fa Hsien, the English seafarer Robert Knox, and the fourth Prime Minister of Ceylon, S.W.R.D. Bandaranaike.

Though little known for his collection of Sherlock Holmes-style writing outside of his more familiar field, the late and much-respected Prime Minister S.W.R.D. Bandaranaike dedicated the last story in the collection to the Esala Perahera.

The story narrates the writer’s proud feelings upon seeing the richness of the culture embedded in the event. The fact that Sinhala was made an official language came as no surprise from such a politician, even though he was raised in a Western environment.

Chessboard of significance

The Perahera has more depth and meaning than procession; in fact, the local term has already become a buzzword among foreigners. Perahera is not just a group moving along in an orderly manner, as its English rendering defines. It can well be compared with a board of Chess; every item carries significance with one or many reasons for taking part.

The Perahera has more depth and meaning than procession; in fact, the local term has already become a buzzword among foreigners. Perahera is not just a group moving along in an orderly manner, as its English rendering defines. It can well be compared with a board of Chess; every item carries significance with one or many reasons for taking part.

The whip-crackers who open the Perahera serve as a kind of “declaration of opening”. They announce the arrival of the rest of the procession. Traditionally, only the Adigars, the high officials in the king’s court, were allowed to employ whip-crackers to announce their arrival.

This was not an essential part of the Perahera and was only introduced during the time of Disawe P. B. Nugawela. The whip-crackers are followed by flag-bearers who represent the provinces and towns they come from. The Peramune Rala, the leading official, is the first to ride on an elephant.

The official who has the right to conduct the Perahera also keeps the records of the temple. The next elephant carries the Gajanayaka Nilame, the chief officer in charge of elephants. He looks regal and upright. The drummers engage seriously in their performance.

This is to be followed by many dignitaries, such as the Diyawadana Nilame, and the royal retinue in the ancient sense.

Illuminating wisdom

The major feature of the Perahera is the use of light. The heavy use of light can be a little debatable when it comes to the energy crisis. However, light symbolises wisdom in Buddhist philosophy, with numerous references. Moving into the light from the darkness means achieving wisdom and ridding oneself of ignorance in Buddhism.

Many Buddhist events, such as Vesak, are celebrated with brightly lit lamps and pandals. Contrary to popular belief, Buddhism is not a grim philosophy. It sees light even in the spiritual life that is free from worldly attachments.

The Perahera is held between Esala and Nikini Poya for a significant reason. Esala marks the Buddha’s first sermon, while Nikini marks the first Dhamma convocation. The Buddha only began teaching after Brahma invited him, as Buddhas traditionally do not preach without an invitation.

The first Dhamma convocation was a critical event, as the teaching was on the verge of collapse following the Buddha’s death. The convocation was attended by 500 Arahant monks, who were presided over by Ven. Kasyapa. Both events symbolise the survival of the philosophy. The Perahera is a fitting celebration of this theme.

Resilience through ritual

The Perahera has its roots in Indo-Aryan tradition and was originally a ritual to invoke the gods’ blessings for rainfall during droughts. The belief in spiritual forces persisted even during British rule. When the Perahera was banned in the first year of British rule, in 1815, a severe drought is said to have followed, crippling the country’s agriculture.

The British were forced to lift the ban on the Perahera after stern protests from the locals. The heavy rains that followed showed the strong local faith in the Perahera, superstition or not.

Invaders have made many attempts to seize the sacred relics, but all have failed.

Invaders have made many attempts to seize the sacred relics, but all have failed.

Some scholars believe that this was an attempt to wipe out the national heritage, while others believe that the British shared the local belief that the sacred relics were essential for royal power.

The Perahera has many origins, apart from its Indo-Aryan roots. As one writer put it, “its origins are lost in the mists of centuries.” The Perahera has evolved over time, taking on different forms. For example, Fa Hsien’s descriptions of the Perahera do not mention the Devale traditions.

Recent history records King Kirthi Sri Rajasinghe as the first lay patron who added colour to the modern Perahera, along with Ven. Welivita Saranankara Thera, the Chief Monk of the country. The king believed that the Perahera should be influenced by Hindu rituals as well, and many Hindu temples were built alongside the Dalada Maligawa.

However, the king had to rethink his policy when Siamese bhikkhus came to Sri Lanka to establish Upasampada ordination. The Siamese bhikkhus were reportedly taken aback by the Hindu elements in the Perahera, and the king ordered the Perahera to be headed by the sacred relics.

Today, however, as Sir Richard Aluwihare notes in The Kandy Esala Perahera, the sacred Tooth Relic is not carried in the Perahera. Only a replica of the casket is carried, as it is considered inauspicious to remove the relics from the sacred precincts.

From sacred saplings to noble tuskers

The ceremony begins with the felling of a jak or rukattana tree, which gives off a milky sap. This is done to mark the opening of the event and symbolise prosperity. Before the tree is felled, it is anointed with sandalwood paste and offerings are made, including a lamp with seven wicks, nine betel leaves, and nine types of flowers.

Elephants and tuskers play a major role in the Perahera and Buddhism as a whole. In the Perahera, only tuskers are privileged to carry the sacred tooth relic. Elephants are often compared to beings who bear all the shortcomings of life in Buddhist texts.

The campaign against the slaughter of tuskers for their tusks is partly rooted in this Buddhist tradition. The Dalada Maligawa has many interesting and moving stories about tuskers who have carried sacred relics. Raja, who is stuffed and on display in the Maligawa Museum, is one such example.

The Kandy Esala Perahera may seem like just another colourful pageant to the casual observer. However, it is much more than that. It is a complex and nuanced event that has survived for centuries. It is a celebration of Sinhalese culture and Buddhist faith, and it deserves to be observed with patience and understanding.