The Buddhist temples of the Southern Province, in particular those going back to the late 19th century, display a uniquely fascinating style. They cannot be viewed in isolation from the Kandyan temples, though as Senake Bandaranayake has noted, it is difficult to ascertain or conclude whether they were an offshoot of the Kandyan Period, or whether they were merely influenced by it.

This debate does not concern us at present: what should concern us is that the murals of these temples reflected their times, and that no two temples, even in the same locality, were ever the same, a point I gathered when I travelled some 55 km from the Sunandaramaya in Ambalangoda to Kataluva in Ahangama a year ago.

This debate does not concern us at present: what should concern us is that the murals of these temples reflected their times, and that no two temples, even in the same locality, were ever the same, a point I gathered when I travelled some 55 km from the Sunandaramaya in Ambalangoda to Kataluva in Ahangama a year ago.

Telltale signs

These temples contain several telltale signs which immediately give away their historical origins. These signs often tend to be more reliable guides than the written word or the oral record. To give just one example, the Sudharmaramaya in Bope, near Poddala, dates to 1736, according to an inscription at the entrance, but it probably goes back much earlier, judging by the architecture, particularly the window railings, which I am told display motifs from the Early Dutch Period.

The murals seem more recent, vaguely reminiscent of the murals at the Sunandaramaya in Ambalangoda. That, of course, belies another point: no two parts of the same temple in these regions are ever the same. The architecture may be 18th century, but the paintings come from a later time, the 19th or even 20th century.

I began my one-day tour across the South last year in a friend’s van. My friend resides in Karandeniya, off Ambalangoda. Since my focus was on Ambalangoda and Balapitiya, all the way to Ahangama, I erred in overlooking the temples in his area. It turned out that the oldest temple in Karandeniya, the Thapodhanaramaya, stood next to his neighbourhood. When I returned to his hometown a few weeks ago, I paid it a visit.

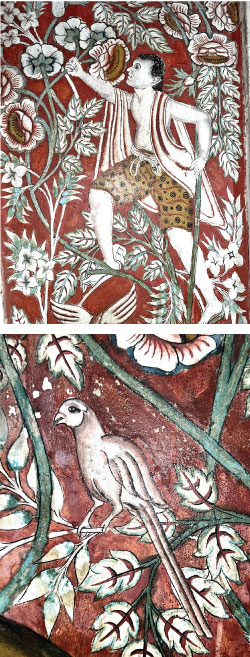

Unlike the Sunandaramaya and the Pushparamaya nearby, the Thapodhanaramaya remains neglected, though it is patronised by locals. According to its chief incumbent, its origins go back to 1856, though he argued that its history may be older. He added that the murals displayed a Kandyan style. This struck me as odd, since they looked undeniably Southern, dating at most to the late 19th century. Of course, I may be wrong.

The Thapodhanaramaya does not appear on Google. To the best of my knowledge, it has not caught the traveller’s or the art historian’s attention. Yet the murals here rank among the finest in the region, comparable to those in the Sunandaramaya or at Randombe. They are sharper and more clearly drawn, certainly much better preserved.

Some of them remind me of the murals at the Subodharamaya at Karagampitiya. One panel, which caught my eye at once, features a group of noble families at the bottom half and two men clad in coat and tie in the top half. That sort of incongruity remains the most recognisable, distinguishing feature of Southern temple murals, and it is very much present here.

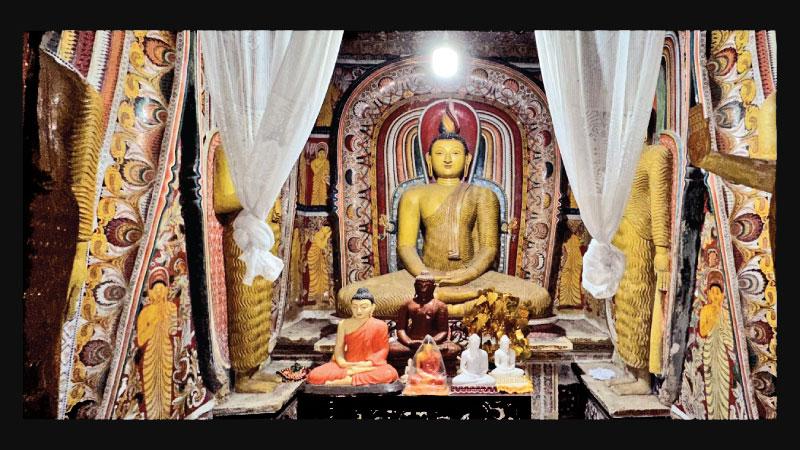

The most interesting mural, which is the subject of this essay, is to be found at the back, at the entrance to the inner sanctum of the temple. It was customary for Southern temples to feature a portrait of the British monarch, and for the most that monarch happened to be Victoria. Her portrait would invariably be flanked by symbols of the British State, including the lion and the unicorn.

That was either a pragmatic response, on the part of bhikkhus and locals, to the reality of British colonialism, or a symbol of their acceptance of the British queen as their sovereign. Given that, I was surprised to come across a portrait, not of a British monarch, but of an unidentifiable man of royal stock. Oddly enough his portrait was flanked by those very symbols of the British State, i.e. a lion and a unicorn.

That was either a pragmatic response, on the part of bhikkhus and locals, to the reality of British colonialism, or a symbol of their acceptance of the British queen as their sovereign. Given that, I was surprised to come across a portrait, not of a British monarch, but of an unidentifiable man of royal stock. Oddly enough his portrait was flanked by those very symbols of the British State, i.e. a lion and a unicorn.

Doomed king

One would be forgiven for assuming, as I did, that the mural represented a Sri Lankan sovereign, perhaps the doomed king himself, Sri Vikrama Rajasinghe. This, however, could not be so, since colonial authorities would not have tolerated a likeness of a king they had deposed half a century ago, at a place which commanded the patronage of locals and local elites. Though this theory should not be dismissed, it remains implausible. What, then, are we to make of the portrait, and who could its subject be?

As always, one requires a closer inspection. And on closer inspection, one discerns several incongruities. The portrait, though resembling a man, seems eerily feminine. The subject is wearing a crown, but he is also wearing a headdress which does not align with the style of Kandyan kings. His eyes seem ethereal, foreign, hardly masculine. He sports a moustache and a beard, but these seem detached from other aspects and symbols.

The crown at the top of the panel also looks British, a point reinforced by the inclusion of the lion and the unicorn. Given these contradictions, it’s difficult to assume, still less argue, that the mural is of a Sri Lankan monarch, specifically the deposed Sri Vikrama Rajasinghe.

A friend put me on the right track. He argued that this was actually a painting grafted on another painting. What did he mean by that? In 1856, the year of the Thapodhanaramaya’s establishment, the British monarch was Victoria. She died in 1901, giving way to her son, Edward VII.

It is possible that the original mural would have been Victoria’s, but that upon her passing, the painters grafted masculine qualities – the beard and the moustache – to resemble her (male) successor. This is a radical, ingenious theory, and I initially doubted it, but after examining the portrait I now concede it. It sounds more probable than the other theory, and it is in line with the period to which these paintings belong.

Understandable omission

It is difficult to say whether this mural is unique to the Thapodhanaramaya, and whether these paintings exist elsewhere. From my travels and my reading, I can only say such murals have not caught the attention of scholars, including art historians. This may be an omission on their part, but an understandable omission, given that the Thapodhanaramaya itself has escaped the historian’s radar. What, then, are we to make of this particular portrait? To me it represents a response, by locals, to events far removed from their home – succession in the British Crown – as well as their perceptions of their new king, a point made more relevant, I think, by the fact that the new king had visited their country in 1875. It is possible that they were sufficiently aware of Edward VII’s features, from that visit, to replace Victoria’s likeness with a likeness of her son. Of course, we may never know.

We must be grateful to Senake Bandaranayake, because his Rock and Wall Paintings of Sri Lanka remains the one stop, indispensable guide to this subject, which is as much a credit to him as it is a critique of those who sought to follow him but never did. The Central Cultural Fund, to which Bandaranaike made a seminal contribution, did much, but after a brief period of activity in the 1980s it appears to have simmered down, no doubt owing to lack of funds and patronage.

What makes this especially poignant is that a great many of these temples and murals are fading away: as with Ozymandias, almost “nothing beside” remains of the magnificent styles and patterns which once distinguished them. It is up to us to capture, if not preserve and restore, these relics. The paintings at the Thapodhanaramaya, the portrait of the mysterious sovereign in particular, underlies that point perceptibly.

The writer is an international relations analyst, researcher, and columnist who can be reached at [email protected].