Sri Lanka’s fiscal landscape left much to be desired even before the repercussions of the Covid-19 pandemic were felt. One year into the pandemic, the country’s already tight fiscal space has become further constricted, leaving some tough decisions to be made in the pandemic recovery period. A third wave of Covid-19 that the country is currently experiencing will further delay such recovery efforts.

Although some fiscal tools have been included in Sri Lanka’s Covid-19 recovery plan, there is general consensus that the size and scale of the country’s fiscal stimulus package have been inadequate against the scale of the crisis. Conversely, wealthier countries have been rolling out some of the historically largest fiscal stimulus packages. This blog discusses the global tilt towards fiscal policy reliance in the aftermath of the pandemic, and deliberate on how far the developing world can adopt a similar strategy.

Global fiscal policy tilt

Even before the Covid-19 crisis, there was a shift in the thinking around loose fiscal policy and fiscal stimulus. New thinking in the developed world is that debt is more sustainable than it was once thought to be and that fears around borrowing and spending leading to inflation are something of the past.

Even before the Covid-19 crisis, there was a shift in the thinking around loose fiscal policy and fiscal stimulus. New thinking in the developed world is that debt is more sustainable than it was once thought to be and that fears around borrowing and spending leading to inflation are something of the past.

This largely stems from the post-global financial crisis (GFC) experience, where unsuccessful austerity measures weakened economies faster than their tax revenues could sustain them. The belief now is that governments can outgrow even large volumes of debt, such that a country’s interest payments can be outpaced by economic growth resulting from the stimulus.

However, this unprecedented level of stimulus that raises concerns of inflation, overheating and reaching unmanageable levels of debt, is of particular worry for developing countries. The assumption of continued loose financial conditions relies on interest rates around the world remaining at low levels. However, large fiscal stimulus in the USA might result in a post-pandemic consumer boom that pushes up prices. Indeed, US inflation rates reached a 13-year high of 5% in May 2021.

This could force the Fed to raise interest rates in order to clamp down on an overheating economy; the consequences of which will impact heavily on developing economies. They could experience capital outflows if interest rates increase in the USA and push up the dollar, thus making it more challenging to manage and sustain high levels of debt, which are usually held in dollars. Finances in this part of the world would suffer as a result, and this would compound the difficulty of fighting the pandemic.

Economic consequences are not felt equally across the world, such that advanced economies and developing economies face different challenges and therefore require different policy strategies for recovery. The key differences lie in: higher poverty rates where more people are made vulnerable due to the pandemic; larger informal sectors where governments find it more difficult to provide assistance; and weak public finances. While governments in wealthier countries have deployed trillions of dollars in fiscal relief measures for pandemic recovery, developing countries do not have the fiscal space for the same.

The need for this type of fiscal support during the pandemic, along with drop in revenue, has raised debt loads to unprecedented levels across the globe. This will have far-reaching consequences for emerging markets and developing economies (EMDEs) in particular, that run the risk of facing a debt crisis.

Debt crisis

Government deficits and debt have risen to unprecedented levels across the board. Average overall deficits as a share of GDP in 2020 reached 11.7% for advanced economies, 9.8% for emerging market economies, and 5.5% for low-income developing countries. Average public debt worldwide reached an unprecedented 97% of GDP in 2020 and is projected to stabilise at around 99% of GDP in 2021.

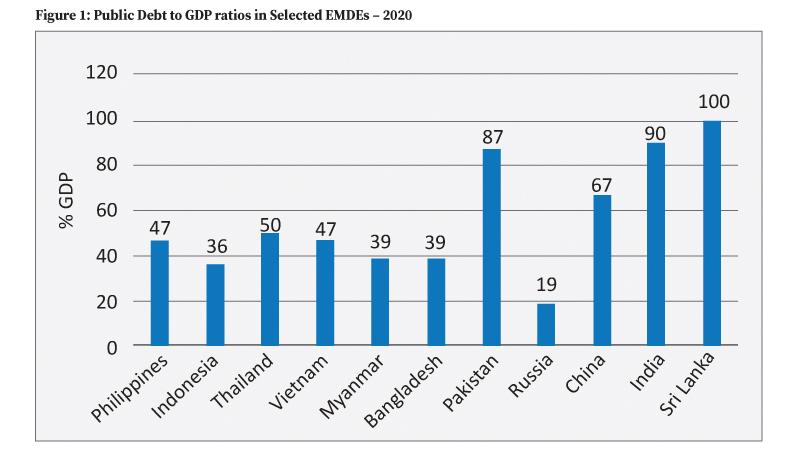

Despite higher debt, average interest payments are generally lower in advanced economies. According to Modern Monetary Theory, advanced economy governments can print money to sustain spending without being operationally constrained by revenue and rising national debt. As issuers of international reserve currencies, they can do so with limited risks. For some EMDEs however, financing large deficits continues to be challenging, given limited scope to raise revenue in the near term (Figure 1).

A recent study by the World Bank classifies a ‘fourth wave’ of debt accumulation to have begun in 2010, whereby global debt has reached USD 55 trillion by 2018, making this wave the largest and fastest-growing of four historical waves. The preceding three waves ended in financial crises—the Latin American debt crisis of the 1980s, the Asian financial crisis of the late 1990s, and the GFC of 2007-09.

Although debt financing can help meet urgent needs, the concern is that the current fourth debt wave is taking riskier forms.

Low-income countries are increasingly borrowing from creditors outside the traditional Paris Club lenders, such as China, as well as from international capital markets. The latter tends to impose nondisclosure clauses and collateral requirements that can make the scale and nature of debt somewhat ambiguous.

Given these characteristics of the fourth debt wave, which is now being further exacerbated by the Covid-19 crisis, already debt-strapped economies such as Sri Lanka will find themselves in a particularly tight spot. In addition, this wave has coincided with multiple challenges for EMDEs, such as weaker growth prospects in a fragile global economy, growing fiscal and current account deficits, and a compositional shift toward short-term external debt, which could amplify the impact of shocks.

In terms of this compositional shift, for instance, emerging market public external debt owed to multilateral institutions dropped from 43% in 2008 to 34% in 2019, while the share for commercial lenders jumped from 29% to 45%, and meanwhile, overall bilateral lending fell.

This shift from concessional toward financial market and non-Paris Club creditors have raised concerns about debt transparency and collateralisation.

Thus, despite exceptionally low real interest rates, the latest wave of debt accumulation could follow the historical pattern and eventually culminate in financial crises in EMDEs. These risks were illustrated by the recent experiences of Argentina and Turkey, which witnessed sudden episodes of sharply rising borrowing costs and severe growth slowdowns.

Striking a balance

Given the above, the developing world is not placed in a comfortable position to expedite discretionary fiscal policy in the manner seen in the advanced world. Specific policies need to be tailored for developing countries, including Sri Lanka, to handle this twin crisis, and specialised support required from the international community.

These can include improving debt management practices to mitigate riskier debt portfolios, improving debt transparency through public debt statistics dissemination practices, improving tax collection and administration, and exploring ways to spend more efficiently, including alternative methods of disbursing cash transfers to households and firms.

This blog is based on the comprehensive chapter on fiscal policy in IPS’ forthcoming ‘Sri-Lanka: State of the Economy 2021’ report.

The writer is a Research Economist at the Institute of Policy Studies, with research interests in taxation, labour and migration, and econometrics and economic modeling.