An old man stands in a dark and musty room. He is wearing a cardboard hat in which is stuck a lighted candle. His friends keep on sending him special candles of goat-fat to be used in the cardboard hat. What is he doing there? Is he out of his senses? No. It is Michelangelo – the man with four souls – working on a sculpture.

The soul is the part of a person that is not physical, and that contains their character, thoughts and feelings. Many people believe that a person’s soul continues to exist even after death. Although a person can have only one soul, Michelangelo had four souls because he had achieved excellence in four disciplines: architecture, sculpture, painting and poetry.

Michelangelo Buonarroti was born at Caprese on March 6, 1475. His father was a mayor. He was born into a family of ancient burgher nobility. With his birth, however, the family lost its wealth, but retained its pride. After losing his position as mayor, his father sent Michelangelo to a stonecutter’s wife to look after him. Michelangelo later said, “I drew the chisel and the mallet with which I carved statues in together with my nurse’s milk.”

Michelangelo Buonarroti was born at Caprese on March 6, 1475. His father was a mayor. He was born into a family of ancient burgher nobility. With his birth, however, the family lost its wealth, but retained its pride. After losing his position as mayor, his father sent Michelangelo to a stonecutter’s wife to look after him. Michelangelo later said, “I drew the chisel and the mallet with which I carved statues in together with my nurse’s milk.”

Young Michelangelo had a passion for art. His father at first tried to prevent him from becoming an artist. But later, he sent his son to Domenico and David Currado who were the leading artists at the time. When they realised his talents, they soon became jealous of him. He studied reality and based his works on naturalism. As a teenager, he began to compare his art with nature. He frequented the fish market to study the shape and colour of the fish. He reproduced the details in his later paintings.

Sculpture

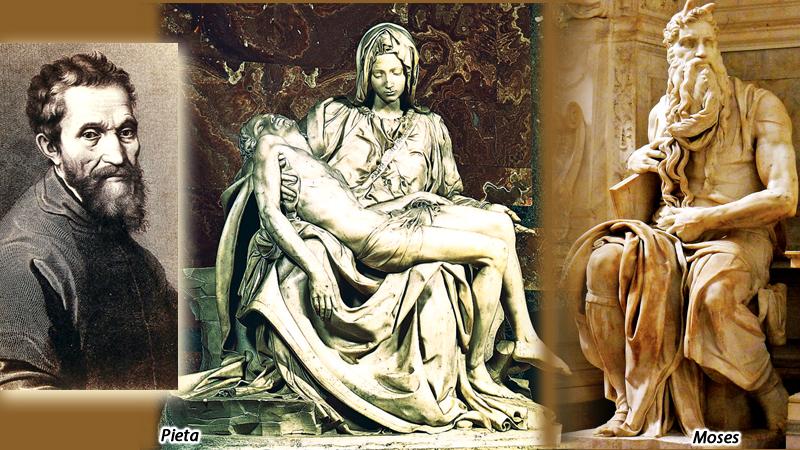

Michelangelo did not stay with his masters for long. He turned his attention to sculpture at the school run by Lorenzo de Medici. While Michelangelo was carving out a grinning mask, Lorenzo spotted it. The teacher admired his mask and advised him how to improve it. Later, Lorenzo took his pupil home where he remained until Lorenzo’s death. Thereafter, Michelangelo came under the influence of Savonarola who was a prophet. Michelangelo studied sculpture and philosophy. For the first time, he read Dante and was fascinated by his knowledge.

Young Michelangelo fell in love with Luigia de Medici, but his love was unrequited. He had to wait till he turned 60 to fall in love once again. He wrote a series of poems to Vittoria Colonna, the widow of the Marquis Pescara. He poured out his soul to her through poetry. However, it remained a platonic love affair.

His biography in the Encyclopaedia Britannica says, “Michelangelo’s poetical style is strenuous and concentrated like the man himself. He wrote with labour and much self-correction; we seem to feel him flinging himself on the material of language with the same overwhelming energy and vehemence with which contemporaries describe him as flinging himself on the material of marble – the same impetuosity of temperament combined with the same fierce desire of perfection, but with far less either of innate instinct for the material or of tainted mastery over its difficulties.”

Masterpieces

As a young man, Michelangelo set about creating his masterpieces one after the other. His “Sleeping Cupid” (1495) was sold to Cardinal di St. Giorgio. In Rome, he carved his marble “Bacchus.” In 1499, he completed the Christian sculpture “Pieta” now found in the Vatican Basilica. In Florence, he produced the “Burges Madonna” and “David.” He also carved “St. Matthew” and drew his cartoon of the “Battle of Pisa.”

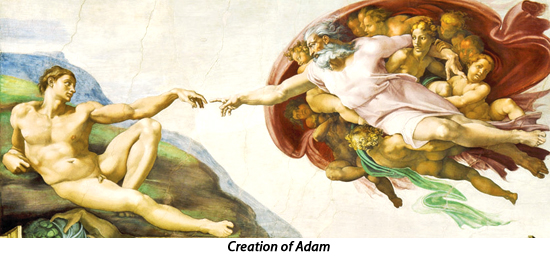

A few years, later Michelangelo unwillingly accepted the commission to decorate the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel. The refurbished chapel was unveiled in 1994. It called to mind a common image of a lonely artist trapped between agony and ecstasy, isolated on his back on a scaffold with a paintbrush in hand. Today, this theory no longer holds water. It has come to light that Michelangelo never worked alone, but he was a savvy executive and manager of people.

Probably, 13 people helped him to paint the Sistine Chapel ceiling. About 20 people helped him to carve the marble tombs in the Medici Chapel in Florence. He had supervised a crew of 200 people for 18 years. Although some of his assistants disappointed him, he never dismissed them. He had enough courage and patience to deal with them.

As a poet, Michelangelo has written two sonnets in Vittoria Colonna’s memory. In 1554, he wrote his sublime sonnet:

“Now hath my life across a stormy sea,

Like a frail bark, reached that wide port where all

Are hidden, ere the final reckoning fall

Of good and evil for eternity.

Now know I well how that fond phantasy

Which made my soul the worshipper and thrall

Of earthly art is vain; how criminal

Is that which all men seek unwillingly.

Those amorous thoughts which were so lightly dressed.

What are they when the double death is might?

The one I know for sure, the other dread.

Painting nor sculpture now can lull to rest

My soul that turns to His great love on high,

Whose arms to clasp us on the cross were spread.”

Last will

In his last moments, Michelangelo made his will in three sentences.He committed his soul into the hands of God, his body to the earth and his substance to his nearest relatives, enjoining upon these last, when their hour came, to think upon the sufferings of Jesus Christ.

Michelangelo, the creative genius, died at 90 in 1564. He was a savvy executive, a man equally at home in the mundane and the sublime. He lived a hard life wedded to his art. According to latest records found in archives in Florence and Pisa, Michelangelo was a man of cultivated tastes. He travelled business class (by mule), or first class (by horse), dressed fashionably in black, drank Trebbiano wine and ate Florentine pears. He knew his helpers by their names and nicknames. He also knew that some of them were unreliable and deceitful. There were people who loved fine clothes more than work. He was satisfied with some of them and others were poor-quality workers. Michelangelo gave 200 of his workers leave, good pay and job security. Some of them worked for him for over 20 or 30 years. There was no work for them only when the cash flow was interrupted by unforeseen circumstances. On rare occasions, he withheld payment for those who fared badly. Although he delegated his work, he closely supervised his men to maintain standards. A friendly priest once asked him why he did not get married and produce children. He said, “I have only too much of a wife in this act of mine. She has always kept me struggling on and my children will be the works I leave behind me.”