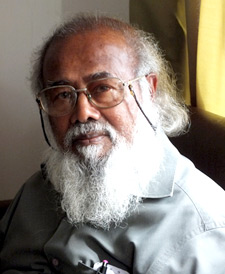

We feature this week an interview with Dr. Anslem de Silva, world renowned Sri Lankan biologist and herpetologist, who is considered the father of modern herpetology in Sri Lanka.

We feature this week an interview with Dr. Anslem de Silva, world renowned Sri Lankan biologist and herpetologist, who is considered the father of modern herpetology in Sri Lanka.

His many achievements include the award for outstanding performance in the field of herpetology and toxinology by the International Society of Toxinologists at the 10th World Congress of Animal, Plant and Microbial Toxins, in November 1991, University of Singapore, Singapore as well as receiving four times the Sri Lanka President’s Award for Scientific Publications in 2011, 2013, 2014, 2016 and in recognition of his contributions towards Herpetology of Sri Lanka being elected as an Honorary Life Member, of the American Society of Ichthyologists and Herpetologists. In 2019, he received the Sir Peter Scot Award of Conservation Merit, the first Sri Lankan to receive this highest IUCN award.

He is the founder and President of Amphibia and Reptile Research Organisation of Sri Lanka (ARROS). Dr. Anslem de Silva is also the regional chairman of the Crocodile Specialists Group of the IUCN, South Asia /Iran and co-chairman of Amphibian Specialist Group IUCN/SSC Sri Lanka.

He has published nearly 500 research publications (which include 60 odd books and chapters in books) on herpetofauna in Sri Lanka in the past five decades.

His current research is of the Saratha Sangrahaya, one of the earliest works authored by King Buddhadasa (340-368 AD) who is reputed to have surgically removed a tumour from a sick cobra.

Dr. Anslem de Silva has conducted many educational programs for traditional snake bite physicians on snakes and their main text book (Sithiyamsahitha Visha Vadiya Chinthmani Vol. 1 by Sisirakumar Liyanarachchi 1971) on traditional snakebite treatment is dedicated to him.

Excerpts

Q: Your fields of study are herpetology, biology, taxonomy as well as Archeology and you are linking these with indigenous knowledge. You are considered the father of modern herpetology in Sri Lanka. Could you detail the beginning of this interest?

A: I was influenced by my father who was the Chief Clerk in the Public Works Department. He loved animals and had animals at home. He died when I was 5 years old.

A: I was influenced by my father who was the Chief Clerk in the Public Works Department. He loved animals and had animals at home. He died when I was 5 years old.

We lived in Matara, our ancestral hometown, close to the sea. I used to catch small crabs in our garden and bury them thinking that they would grow and multiply.My herpetology journey started at the age of 7.

This beachfront ancestral home in the Fort, Matara, has been an abode to a few marine turtle hatchlings, star tortoises, snakes, a hatchling saltwater crocodile (Crocodylusporosus) and a land monitor (Varanusbengalensis).

My first exposure to wild turtles, terrapins and tortoises of the country was in the early 1950s’ when I was a student of St. Servatius’ College, Matara. My everyday walk to school entailed my passing through a lonely stretch of beach front from the Matara Ramparts to the school.

Some parts of the road were flanked with scrub jungle, and the beach side with Ipomea and many pandana trees (Pandanusodoratissimus).

Morning walks to school brought me face-to-face with disoriented green turtle hatchlings (Cheloniamydas) straying onto the metalled road and heading landward. I would pick them up and place them near the shore facing the sea, eager to witness their race toward the waves, and watched with amazement as the hatchlings scrambled, undaunted, towards the ocean.

Q: Today, children grow up in artificial settings, far removed from the natural world. Yet we speak the rhetoric of sustainability. Your views?

A: Today’s children have modern technologies: computers, smart phones, TVs by which they can learn a lot - more than what we knew –, but they will have no time to see the real nature, to live, experience and be a part of the natural world. It would be nice if teachers can take children regularly to various ecosystems so that they can experience nature. Respecting the concept of sustainability which is what our traditional way of living is about, should begin at a young age.

Q: It is known that the first book that influenced you to study reptiles by travelling throughout the country was Snakes of Ceylon written by Frank Wall. How do you rate the existence of biodiversity or ecosystems that protect snakes?

A: Frank Wall’s Snakes of Ceylon (1921) was presented to me by my late brother Noel de Silva in 1958. In the long walks I have undertaken to see nature, I have seen many snakes by road side thickets. These thickets are now rare. They have been replaced with concrete jungles.

I live in a forest garden cottage in Gampola, Kandy with a rich diversity of fauna and flora – busy with a half-acre organic farm.

What we see today is that animals are getting extinct fast due to manmade reasons - habitat loss and fragmentation, pollution, invasive species,chemical agriculture, pathogens and diseases, road kills and climate change. The excessive application of agrochemicals is a key reason for the loss of biodiversity. The use of chemicals has increased over the past three decades, especially in paddy fields, vegetable and tea plantations.

What we see today is that animals are getting extinct fast due to manmade reasons - habitat loss and fragmentation, pollution, invasive species,chemical agriculture, pathogens and diseases, road kills and climate change. The excessive application of agrochemicals is a key reason for the loss of biodiversity. The use of chemicals has increased over the past three decades, especially in paddy fields, vegetable and tea plantations.

Reptiles, amphibians, birds and mammals get killed due to road/air traffic, pollution of marine habitat by ships and oil spills. This is a reason why most of our reptiles and amphibians are becoming critically endangered, (116 species of amphibians).

According to the IUCN Red List (IUCN, 2020), of threatened species, 72 (62%) species of amphibians in Sri Lanka are threatened with extinction, either directly or indirectly, 18 species are extinct and 20 species are critically endangered.

Of the known 221 species of reptiles, nearly 40 are critically endangered.

Q: Sri Lanka has had for thousands of years a precise and detailed indigenous medical system, a part of the Deshiya Chikitsa/Sinhala Wedakam or Hela Wedakam tradition that predates Ayurveda which had an intriguing branch of healing that deals with the animal world, especially snakes and pertaining to the removal of poison from the human body through diverse processes. Could you explain if/how the survival of this tradition is important for the sustainability of the ecosystem?

A: I am doing a research on the Saratha Sangrahaya, one of the earliest works authored by King Buddhadasa (340-368 AD) who is reputed to have surgically removed a tumour from a sick cobra.

Many statements in Saratha Sangrahaya, are what modern researchers find. Another important statement in traditional snakebite treatment is Visen visa nasi (to kill/neutralize venom, you need venom) – this is exactly what modern antivenin serum is doing. I conducted educational programs for traditional physicians on snakes years ago.

Their main text book on traditional snakebite treatment was dedicated to me. (Sithiyamsahitha Visha Vadiya Chinthmani Vol. 1 by Sisirakumar Liyanarachchi 1971).

Q: How many snakes are killed per day in Sri Lanka?

A: There are no studies on this aspect, except random studies in certain areas. For example, in 1999, I reported that road kills could cause serious problems to populations of reptiles, such as Aspiduratrachyprocta and Calotesnigrilabris in Horton Plains as the number of visitors and vehicles arriving at the Horton Plains National Park kept increasing daily.

One of my herpetology students and I conducted a study on this. This research was based on a six-kilometre stretch of the road from the Matale junction to the main gate of the Rajarata University of Mihintale along the Anuradhapura-Mihintale road, which was selected to determine the pattern of reptile mortality due to road traffic.

The survey was conducted from March to December 2006. Observations were conducted by visiting the sampling area for about 15 days each month while cycling slowly on a push bicycle. Run-over amphibians and reptiles were photographed, and brought to the laboratory for identification and preservation. Data, such as the habitat type on either side of the road kill and the part of the body run over were recorded in a data sheet. During the study, 138 reptile road kill specimens belonging to 24 species were collected. These comprised seven agamid lizards, 11 chelonians, 10 varanids and 110 snakes. Rare species, such as the Brown Vine snake Ahaetullapulverulenta (Henakandaya) and a number of endemic species were included.

Of the snakes, the most frequently run over were the Buff-striped Keelback Amphiesmastolatum and the Checkered Keelback water snake Xenochrophisspecies. The Chelonian road kills include Melanochelystrijugathermalis (Spotted Black Turtle), Geocheloneelegans (Star Tortoise) and Lissemyspunctata (Flapshell Turtle). No gecko or skink road kill was found during the study. The incidence and pattern of the reptiles killed varied with the habitat type of the study site, species and age class of the reptile and the weather conditions. Based on these observations, conservation measures and recommendations to protect and decrease the number of reptiles killed on the Anuradhapura-Mihintale road by traffic have been suggested.

Herpetologist Sameera Karunaratna et al published another paper a few years ago on road traffic mortality. Many animals get killed in our roads annually.

Q: Are most snakes venomous or harmless?

A: Of the 105 species of snakes, only a few have caused deaths to humans: russells viper, two krait species, cobra and the hump nose vipers (polonthelisa), but of course, the 15 odd marine snakes are highly venomous.

Many people kill harmless snakes assuming that they are venomous vipers. During the early stages of the Mahaweli project, I was a consultant on snakes and snakebite to new settlers. I can remember that most drivers purposely ran over vipers to kill them.

Q: Are there legal provisions to protect snakes?

A: According to the Fauna and Flora Protection Ordinance, snakes are protected – but killing venomous snakes is ‘allowed’. Venomous and non-venomous snakes are killed out of fear and ignorance, as a precautionary measure against snakebite.

This frequently happens in agriculture related activities e.g. harvesting, weeding, guarding fields and cutting grass. Rural domestic hazards are caused mainly by kraits (Bungaruscaeruleus and B. ceylonicus).

Q: Can’t we train youth to save snakes? This is done by a young man in Habarana; Puthrasigamani Jeganathan, who has been saving snakes in the vicinity for no personal benefit for about two decades and has now trained a battalion of snake savers who promptly go to houses to save snakes. Jeganathan’s son is also a snake saver! Can’t this be done at a national level?

A: Yes, it should be done at a national level. This is popular in India. Wildlife Conservation Minister and the Director General can discuss with experts and start to train youths who are willing to study about snakes and on saving snakes. Puthrasigamani Jeganathan is a good friend of mine.

Q: Why are snakes important to the eco system?

A: They add to the bio-diversity of the country. They help farmers by feeding on rodents. Snake venom is used in preparation of medicines. Pertaining to ecotourism – many foreign herpetologists visit Sri Lanka to see some of our endemic snakes.

Q: As the founder and President of the Amphibia and Reptile Research Organisation of Sri Lanka (ARROS), could you detail the functions of the organisation?

A: We have conducted awareness programs for the people, such as in schools and for wildlife personnel on reptiles and amphibians. We have published the first herpetological journal in the country. We also held international and national conferences on herpetology, including the World Congress of Herpetology.

Q: You have published almost 500 research publications related to herpetofauna over the past five decades. Could you detail a few of them important for people?

A: Anslem de Silva. 2003. The biology and status of the star tortoise in Sri Lanka.Ministry of Environment and Natural Resources.

Anslem de Silva. 2005 (Editor).Diversity of the Dumbara Mountains (with special reference to its herpetofauna).

Anslem de Silva. 2009. Amphibians of Sri Lanka: A Photographic Guide to Common Frogs, Toads and Caecilians.

Anslem de Silva. 2009. Snakes of Sri Lanka: A coloured Atlas, VijithaYapa Publications, Colombo.

de Silva, Anslem. 2013. TheCrocodiles of Sri Lanka (Including Archaeology, History, Folklore, Traditional Medicine, Human-Crocodile Conflict and a Bibliography of the Literature on Crocodiles of Sri Lanka). Published by the Author.

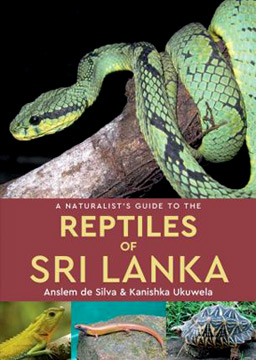

Anslem de Silva and K. Ukuwela. 2020. A Naturalist Guide to Reptiles of Sri Lanka. (2nd Edition) John Beaufoy Publishing ltd. UK.

De Silva, A. and Lenin, J. (2010). Mugger Crocodile Crocodyluspalustris.Pp.94-98 in Crocodiles.Status Survey and Conservation Action Plan.Third Edition, ed. by S.C. Manolis and C. Stevenson.