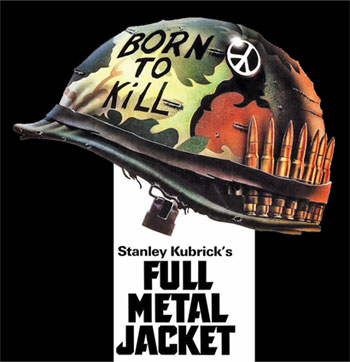

Stanley Kubrick’s uncontested masterpiece of war cinema, Full Metal Jacket, told in a unique two-act structure, Full Metal Jacket feels unlike most traditional films, which Kubrick had a knack for.

In the first half, we are thrust into boot camp right along with a new, fresh batch of recruits. For the first fifteen minutes of Full Metal Jacket you will experience a solid wall of ingeniously  phrased profanity and systematic re-socialisation of the boys at the hands of Gunnery Sergeant Hartman (R. Lee Ermey). Here, we see relentless examples of the ‘Marine Corps’ goal (in Kubrick’s eyes) to strip away the identities of these young men and replace them with the hearts of killers. As Sergeant Hartman trains the recruits, he uses a number of brutal tactics from outright physical abuse to more devious sociology. All of this process is seen most effectively through Private Leonard ‘Gomer Pyle’ Lawrence (Vincent D’Onofrio). At first Sgt. Hartman assigns Private Joker (Matthew Modine) to oversee the struggling and overweight Lawrence. But as Lawrence continues to make mistakes, Hartman eventually turns the troops against Pyle by punishing them each time he messes up. The slow process of institutionalisation works its devious ways and all of the men turn against Pyle. He finds his gifts as a marksman, however. Hartman will succeed in turning his men into killers. But Pyle’s fate is one of the most profoundly harsh tales I can ever recall seeing.

phrased profanity and systematic re-socialisation of the boys at the hands of Gunnery Sergeant Hartman (R. Lee Ermey). Here, we see relentless examples of the ‘Marine Corps’ goal (in Kubrick’s eyes) to strip away the identities of these young men and replace them with the hearts of killers. As Sergeant Hartman trains the recruits, he uses a number of brutal tactics from outright physical abuse to more devious sociology. All of this process is seen most effectively through Private Leonard ‘Gomer Pyle’ Lawrence (Vincent D’Onofrio). At first Sgt. Hartman assigns Private Joker (Matthew Modine) to oversee the struggling and overweight Lawrence. But as Lawrence continues to make mistakes, Hartman eventually turns the troops against Pyle by punishing them each time he messes up. The slow process of institutionalisation works its devious ways and all of the men turn against Pyle. He finds his gifts as a marksman, however. Hartman will succeed in turning his men into killers. But Pyle’s fate is one of the most profoundly harsh tales I can ever recall seeing.

There are sequences of Pyle being abused and tormented by his fellow recruits, as well as by the drill sergeant, which have haunted me since my teenage years when I first saw the film. As a matter of fact, the entire first half of Full Metal Jacket was essentially etched in my brain and I remember it well all these years later.

The second half of Full Metal Jacket follows Modine’s character (now Sergeant Joker) into Vietnam. We sort of go where he goes in a more free and floating structure that culminates in a set piece where Joker’s platoon is ambushed by a sniper. Upon finally smoking the sniper out and wounding her in the process, the soldiers discover that the sniper who killed some of their friends is, in fact, a young girl who is dying slowly and painfully. In a masterfully tense sequence, Sergeant Hartman’s killer training succeeds once again as Joker takes the life of this young girl.

Full Metal Jacket is a master study in indoctrination and fundamental identity shifts. Every moment of the film builds and builds on Kubrick’s ideas that the military strips young men of their prior lives and rebuilds them into something else entirely. Both Private Pyle and Private Joker successfully undergo a metamorphosis at the hands of Uncle Sam. And the results are haunting.

The concept of being stripped of your identity and given a new one brings to mind the question of who your master is. Hartman’s goal as a drill sergeant was to take all the men and, no matter their previous allegiances, make sure that their master is the United States. Or better yet, the Marine Corps. At one point he even states, “You can give your heart to Jesus, but your ass belongs to the Corps.”

When a person seeks out change in their life and looks for redemption or forgiveness, it is possible for such radical tactics to be a healthy environment for them. For instance, the strict and regimented life in an addiction recovery clinic might provide exactly what someone needs to become whole or healed once again.

But in the case of the Marine Corps, and Privates Pyle and Joker, they are forced to essentially place the god of war on the altar. I’m reminded of the very first commandment, “You shall have no other gods before me.” In Kubrick’s film, he poignantly displays the effects of making war your idol. And the consequences for both men are disastrous, although to varying degrees. Trying to write about a film as masterful as Full Metal Jacket is somewhat intimidating. I haven’t even skimmed the surface of the many levels Kubrick has infused into his film. But I think the ideas I’ve talked about are at the core of what he was trying to communicate.

Sadly, I have to say that the image quality wasn’t as sharp or clean as I feel it could have been. This is a masterfully and meticulously crafted film that deserves the greatest high definition transfer that money and technology can achieve. So, although it looks good, I’d have loved to see it look even better.