By Dr. B. Kaluarachchi, President C.N.A.P.T

Despite its eradication some time ago, Tuberculosis (TB) is proving to be the scourge of the 21st Century as it appears to raise its head again with a vengeance.

TB as it is commonly known is posing a serious health hazard in the industrialised world while in the developing world, it is out of control, according to a variety of health officials.

The re-occurrence of TB has brought many complications. Historical statistics show us that more people died of the lung diseases in 1995 than in any other year in history, according to officials at the World Health Organization (WHO), who declared a global emergency.

The re-occurrence of TB has brought many complications. Historical statistics show us that more people died of the lung diseases in 1995 than in any other year in history, according to officials at the World Health Organization (WHO), who declared a global emergency.

That year, TB claimed the lives of nearly three million people, surpassing even the worst years of the epidemic around 1900, when an estimated 2.1 million people died annually.

Resurgence

What is worrying for us Sri Lankans should be the fact that the majority of deaths – 95 percent continue to be in the developing world. However, the industrialised nations, which, for decades, thought they had rid themselves of the diseases, are also seeing a resurgence. The number of TB cases is on the rise in Denmark, Norway, the Netherlands, Italy, Britain, the US and many other industrialised countries, said WHO officials, who warn the crisis will grow unless immediate action is taken.

“Most people in the developed world thought that TB was a thing of the past” in our grandparents’ generation, it was one of the diseases that everyone feared. But for people in the wealthier countries, it is just not something that we worried about any more. It is a common outlook in the west.

This belief has proven to be the industrialised world’s biggest mistake. It seems, while the West basked in a false sense of security, TB raged on in the poorer countries of the developing world and unsuspectingly rode on the movements of mass migration, to turn up on the doorsteps of the wealthy nations again.

And this time, the epidemic may prove even harder to stop, health officials warn. The officials said that the emergence of drug- resistant strains of TB threatens to make the disease incurable, as it was before the discovery of antibiotics in 1944. That raises the spectre of a return to an age when diagnosis of TB was tantamount to a death sentence.

“Not only has TB returned. It has upstaged its own horrible legacy.”

Multidrug-resistant TB has been reported in New York City, London Milan, Paris, Atlantes and Chicago and in cities throughout the developing world. The number of cases of this form of TB is expected to rise particularly rapidly in Asia, unless control measures are urgently strengthened there, WHO officials said.

A global threat

Tuberculosis, an epidemic assumed by most people to be a thing of a past, still increasing globally. It’s back with a vengeance and once again posing a serious threat to the developed world and is running out of control in the developing world. It has returned in a form worse than ever. It has been reported that more people have diet of the disease in 1995 than any other year in history. It is said that 1/3 of the world population are infected with TB and someone in the world is newly infected every second of everyday.

Left untreated, a person who developed active TB will infect an average of 10-15 other people every year. Effective drugs that cure active TB have been available for more than 50 years, yet nearly 2,000,000 people a year still die of the disease.

Eight percent of the world’s Tuberculosis cases are concentrated in 22 high burden developing countries. Mobile populations, the HIV/AIDS epidemic and an increase in multi drug assistance on Tuber have made the World Health Organization to declare TB a global emergency in 1993.

Tuberculosis is expected to rise rapidly in Asia unless control measures are urgently strengthened there, WHO officials said.

Tuberculosis, a highly infectious disease which attacks the lungs, has, in fact, been curable for almost 50 years with a simple and relatively inexpensive course of antibiotics. But poorly implemented treatment programs and incomplete antibiotics therapy have given rise to the new killer strains. When you start a course of antibiotics on a patient, they are feeling awfully sick and are often coughing up blood and feeling feverish and very ill. But after a month or two of treatment, they feel better. They imagine that the disease has gone, so they don’t finish the course. Later, perhaps months or even years later, the person goes down with the disease again, and when you the antibiotics again, they don’t work.

New strains

You may be successful in diagnosing a patient with TB, but unless you can follow that through with the right therapy for at least six months, you will end up with pockets of resistance to the disease. Health authorities in New York City were among the first in the industrialised world to come up against the problem of the new strains of TB.

For some multidrug resistant strains of TB, there is simply no cure. In poor countries when you have multidrug – resistant TB, it is a death sentence, because they just don’t have a wide array of antibiotics to use. In the industrialised world, drug resistant form of the disease can be treatable, but even then, 50 percent of the time, even in Europe and the US, people die of it.

Research estimates that already, at least 50 million people worldwide are infected with strains that are resistant to at least one of the four common antibiotics used to treat TB. A staggering one third of the world’s population is now infected with the TB bacillus. Over the next decade, it is estimated that 300 million more people will become infected, 90 million will develop the disease and 30 million people will die from it.

TB is the world’s leading single infectious killer. It strikes young and old alike and kills more women each year than all the causes of maternal mortality put together.

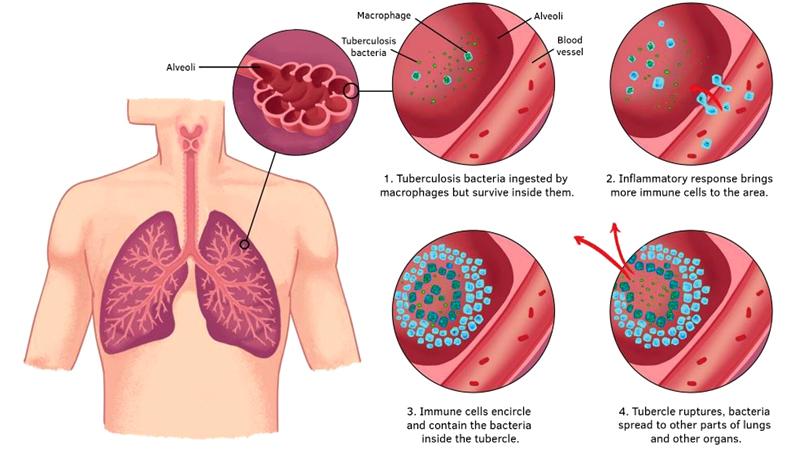

TB whose symptoms include coughing up blood, raging fever and severe loss of weight attacks the victims’ lungs gradually destroying the living tissue, eating ragged holes in the organs. As their lungs are consumed, the sick patients die through asphyxia by virtually drowning in their own blood.

Only a relatively small percentage of people who are infected with the bacteria will develop the disease. TB is spread through the air easily when an affected person sneezes, coughs, even talks, suspending the bacilli in the air which can in turn be inhaled by others.

Immune system

“Most people will never get sick. If you have a healthy immune system and you breathe in this bacterium, you only have a 5-10 percent chance of going down with the disease,” said Singer. But unsanitary living conditions, or a poor state of general health provides ideal conditions for the bacteria to take hold in the body and to develop from a passive to a full blown active phase.

That goes some of the way towards explaining why immigrants to the industrialised world are proving particularly vulnerable to the disease, said health officials. The first and most important reason for the comeback of TB in the industrialised world is immigration. There has been a mass movement from the poor countries to the rich countries. The immigrants don’t arrive here with the disease, but they are infected.

Only people with active TB can infect others. But unhygienic living conditions and a poor diet – all problems associated with immigrants in a new country – can quickly turn dormant TB in to the disease itself. “Immigrants often live in undesirable conditions and live of a poor diet. This lowers their immune defense system and the disease erupts,” said Dr. Arosa.

In the right conditions, especially where living quarters are poorly ventilated, TB can spread like wild fires. One member of the group who unwittingly had dormant TB soon developed the disease, and the bacteria quickly spread to the others.

There is nowhere to hide from Tuberculosis, said a WHO Global TB Program official. Anyone can catch TB simply by inhaling a TB germ that has been coughed or sneezed in to the air. These germs can be suspended in the air for hours, even years. We are all at risk.

The world is becoming smaller and the TB bugs becoming stronger, he added. While international travel has increased dramatically, the world has been slow to recognise that the poor TB treatment practices of other countries are a threat to all their citizens,” he said.

If countries have been slow to react to the danger of the spread of TB, airlines could unwittingly be putting their passengers at risk. There have been some recent documented cases of air travellers who have caught TB from fellow air line passengers.

High-risk segment

Left untreated, a person with active TB will typically infect a further 10-15 people in the course of a year. Another high-risk segment of the population includes people with the Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV), the causative agent and precursor of AIDS (Acquired immune Deficiency Syndromes). The HIV virus lowers the body’s defences against opportunistic disease, such as TB, making the victim much more vulnerable to infection.

If you become infected with HIV, your immune system is depressed and that is when, if you are carrying around the TB bacteria in your system, you are likely to develop the disease. The people with HIV can more easily catch TB infection from others who already have it.

Increasingly, the two killer diseases - AIDS and TB - go hand in hand. One third of all people who die of AIDS worldwide are actually dying of TB, health officials said. It is the leading killer of HIV-positive people in the world. This is especially a problem in Asia and Africa, though we have also seen TB spreading on HIV wards in the industrialised world.

Of the 14 million people known to be infected with HIV in 1994, the latest year for which figures are available, 5.6 million were also believed to be infected with TB. The deadly partnership between AIDS and TB is taking a particularly heavy toll on parts of the developing world.

Why cannot Tuberculosis be conquered simply? It is due to the low priority given to Tuberculosis by health policymakers. In many low to middle income countries, less than one percent of the annual health budget is allocated for Tuberculosis. Why? Because, TB is something to be swept under the carpet, covered up. Its existence is ignored. The tragic consequence is, because of inadequate funding, inefficient TB control programs have led to the worsening of world TB situation. This is because the patients are not cured but do not die of the disease, either leading to a pool of inadequately or improperly treated patients.

Poor TB control

Disseminating multi drug resistant TB in the community, in other words, a poor TB control program, will contribute to many patients dying of the disease though there will be no half treated, half dead patients, and therefore, these people will continue to disseminate the disease to healthy people. Also, multi- drug resistant TB is man made by doctors, the patients themselves and the drug companies. Doctors may prescribe drugs in the wrong dosage or combinations, or because, the patient may have to buy all the drugs for the prescribed period, in addition to paying the consultant’s fee. Drug companies may produce poor quality drugs which may not have the correct quantity of the drug in them.

However, all is not gloomy. It has been shown conclusively in countries poorer than Sri Lanka such as Nepal and Bangladesh, (with per capita GNPs of around US$ 200 compared to a per capita GNP of US$ 840 for Sri Lanka) that more than 90 percent of tuberculosis patients can be cured and the emergence of multi-drug resistant tuberculosis controlled if the treatment of Tuberculosis patient is completely supervised, in other words, if someone (nurse, health volunteer worker public health worker, a relative) watches the patient swallowing the drug.

Tuberculosis patients (or for the matter, any patient) have the bad habit of forgetting to take their drugs when they feel better. The very efficacy of modern anti-tuberculosis drugs is a disadvantage, because patients feel normal too soon, leading them to forget to take their medication or take it irregularly. Directly supervised treatment circumvents this hurdle and has now been shown to be the only way rampant tuberculosis can be controlled. This method of treatment has been given the acronym DOTS – directly observed treatment short course - and has been proven to dramatically improve cure rates and reduce the incidents of multi-drug resistant tuberculosis in countries as diverse as the Philippines, Peru, China, Bangladesh, Nepal, Thailand, Cambodia, Ghana, Tanzania and Indonesia.

However, DOTS is not easy. It needs a wide network of health institutions close to the patient’s hope. In this respect, Sri Lanka is much more fortunate than most Asian Countries because of the solid health infrastructure, with any health institution within 1.4 km of a patient’s home or a western type of the government health institution within 4.8 km of a patient’s home.

In Yemen, for example, the distance between two health intuitions may be more than 75km. All that is needed in Sri Lanka is for these health institutions (General and District Hospitals, Rural Hospitals) peripheral units and central dispensaries) to be stocked with adequate anti-tuberculosis drugs and dedicated to start the administration of the drugs to the patient on a daily basis. (ie DOTS). This has been implemented in the Galle and Kandy district with remarkable results. Cure rates in the Galle district have risen to more than 85 percent from a previous 75 percent. Defaulter rates (patients absconding treatment) have fallen dramatically.

An area which leaves much to be desired in the Sri Lankan context is greater involvement of NGOs in recruiting and mobilising volunteers for treatment supervision. In Bangladesh, a non government organisation BRAC conducts one of the most efficient (probably the most efficient tuberculosis program in the world, entirely outside the government health service, run by volunteer mobilisation.

In Japan, where the royal family itself had casualties from Tuberculosis in the past, the Japan anti-tuberculosis women’s association has a membership of more than 4.2 million active members – this, in a country that is one of the richest in the world with one of lowest tuberculosis prevalence. Each member of the association contributes 100 Yen a year, leading to an annually income of nearly 4,200,000,000 Yen. All this money is used to improve tuberculosis control in Japan and other impoverished countries. If Japan takes the Tuberculosis problem so seriously, how come we don’t?

Sri Lanka’s situation

Compared to other South Asian countries, Sri Lanka is far ahead in terms of quality of life, life expectancy, literacy, maternal mortality and infant mortality. This is a constant source of amazement to developed countries, such as Japan, that wonder how we can maintain such indices comparable to a developed country in spite of other factors, such as ending the battle against terrorism. The answer is the standard of literacy and education of the population and the solid health infrastructure.

It would be tragic, indeed, if the tuberculosis situation in the country was allowed to deteriorate in spite of possessing such a proud record in health care.

Educating the public is the most important part of TB eradication. The Ceylon National Association for the Prevention of Tuberculosis (CNAPT) has been in the forefront of the campaign for educating the people in Sri Lanka on TB prevention over the past 72 years. It has worked in partnership with the Ministry of Health and a diverse range of civic society partners in promoting knowledge and understanding on the disease among the vulnerable section of the population and improving their access to proper medical care.

Last year, the CNAAPT with financial assistance received from the Global Fund for AIDS, TB and Malaria (GFATM), sponsored a knowledge, Attitude and Practice behavior that stands against the national efforts at the TB eradication program. A TB study undertaken in collaboration with the Medical personnel of the Respiratory Disease Control Program of the Ministry of Health was assisted by the Centre for Social Survey and the University of Sri Jeyawardenepura.

The CNAPT has also started a health education program on TB assisted by the Global Fund to disseminate knowledge on TB, its spread, its prevention and management and to let the public know where to get the help and assistance they require. The primary target groups of this education campaign launched by the CNAPT are the school teachers aimed at taking advantage of their strategic position and spreading the message through their pupils to society at large.