Through a review of official records spanning nearly 25 years, Sunday Observer has traced the origin and evolution of the military agreements between the governments of Sri Lanka and the United States, which have entered the public spotlight for the first time after several prominent media outlets alleged that new revisions to the agreements had set the stage for armed US troops to roam freely throughout Sri Lanka and construct military installations on the island.

The need for a formal arrangement between the two countries first arose in 1995, when the sudden sinking of two navy vessels by the LTTE in Trincomalee, shattered the ongoing peace talks and drove the country back into civil war. The United States, an ally who had backed the peace process, was one of the countries that immediately readjusted to the need for Sri Lanka to pivot to a war footing, and offered the government substantial military assistance, including training services for Sri Lankan officers.

The need for a formal arrangement between the two countries first arose in 1995, when the sudden sinking of two navy vessels by the LTTE in Trincomalee, shattered the ongoing peace talks and drove the country back into civil war. The United States, an ally who had backed the peace process, was one of the countries that immediately readjusted to the need for Sri Lanka to pivot to a war footing, and offered the government substantial military assistance, including training services for Sri Lankan officers.

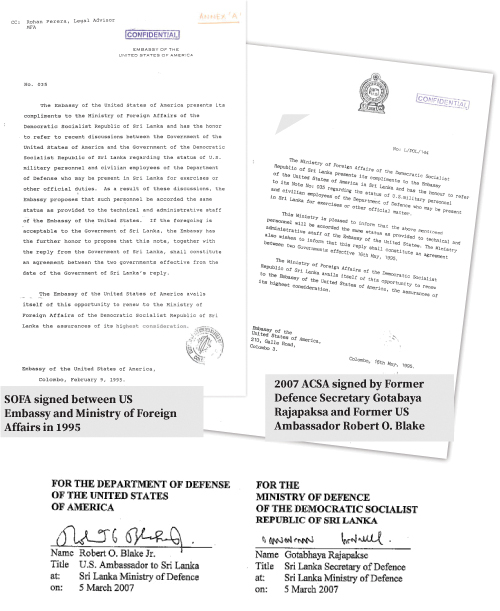

Part of the military aid that the Sri Lankan military was especially keen to accept was for US military officers to relocate to Sri Lanka and embed with our forces as advisors, primarily to provide training and logistical assistance. For these initiatives to get off the ground, one issue that had to be decided was the status to be accorded to US military personnel who were brought to Sri Lanka at the invitation of our government. In February 1995, prior to the outbreak of hostilities, according to a diplomatic note seen by the Sunday Observer, the US government had proposed that “such personnel be accorded the same status as provided to the technical and administrative staff of the Embassy of the United States in Colombo.”

A few weeks after the LTTE declared war, on May 16, 1995, President Kumaratunge and Foreign Minister Lakshman Kadirgamar, accepted these terms via diplomatic note, and thus began the first formal agreement on the “status of forces” – or SOFA – for US military personnel present in Sri Lanka for exercises and other official business, at our country’s invitation.

“The Ministry is pleased to inform that the above-mentioned personnel will be accorded the same status as provided to technical and administrative staff of the Embassy of the United States. The Ministry also wishes to inform that this reply shall constitute an agreement between two governments effective 16th May, 1995.”

The agreement, while a novel step for Sri Lanka, was not alien to the United States, which has similar agreements with several countries in the region, including Singapore, the Maldives, Seychelles and South Korea. One neighbor which does not have a publicly acknowledged ‘SOFA’ agreement with the United States is India.

Military relations between India and the United States are governed by four foundational agreements, covering mutual logistical support and intelligence sharing between the countries. In addition, the two governments hold an annual fortnight-long exercise, named “Yudh Abhyas”, in which large numbers of US troops visit India, or vice versa, to conduct joint training and maneuvers.

From December 2005, with American citizen and US-trained infantry officer Gotabaya Rajapaksa returning to Sri Lanka to take over the Defense Ministry as ministry secretary, military relations with between the United States and Sri Lanka grew even closer than they had been during the Kumaratunge presidency. According to diplomatic cables reviewed by the Sunday Observer, the former US Ambassador in Colombo, Robert O. Blake, said that Rajapaksa would cite “strong personal connections between the United States and his country’s leadership,”in bilateral discussions, an allusion to the fact that his family, as well as the families of two of his brothers, were US citizens and residents.

The tightened bond is equivalent in many respects to how relations between Sri Lanka and Australia grew stronger during the same period, with Australian citizen Palitha Kohona serving as Secretary to President Rajapaksa’s Foreign Ministry.

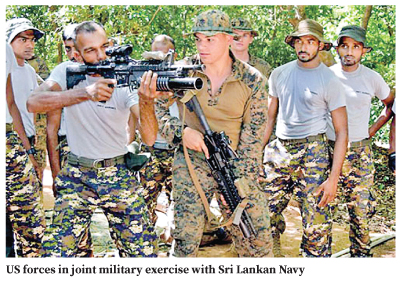

The strengthening of relations during the Rajapaksa-era was symbolized by the sudden progress in the “Acquisition and Cross-Servicing Agreement” or “ACSA” that the US had been lobbying the Sri Lankan government to sign since 2002, according to US diplomatic cables reviewed by the Sunday Observer. But after five years of failed negotiations with the successive governments of Prime Minister Ranil Wickremesinghe and then President Kumaratunge, in 2007, the US finally got a lucky break in renewing their negotiations with Gotabaya Rajapaksa.

“On January 27, 2007,” a leaked cable gloats, “Secretary Rajapaksa stated that he was ready to sign the agreement at anytime convenient to the US.” The sudden breakthrough is attributed to the ease of negotiating with a single family.

Instead of having to convince politicians and bureaucrats across the government, the US ambassador merely had to sell Gotabaya Rajapaksa, who in turn got permission from the rest of his family, President Mahinda Rajapaksa, Speaker Chamal Rajapaksa and Economic Development Minister Basil Rajapaksa, to enter the agreement. The process could be expedited without having to go before Cabinet or Parliament.

At the request of the US Embassy, Rajapaksa agreed to finalize and sign the agreement in secret at the Ministry of Defense, and the agreement was finally signed on February 28, 2007 by Secretary Rajapaksa and Ambassador Blake. The agreement bore fruit for both countries. The Rajapaksa government used it to signal tacit US backing for the renewed military campaign against the LTTE, and the US gained an additional logistical hub for its forces transiting through the South Asian region.

At the request of the US Embassy, Rajapaksa agreed to finalize and sign the agreement in secret at the Ministry of Defense, and the agreement was finally signed on February 28, 2007 by Secretary Rajapaksa and Ambassador Blake. The agreement bore fruit for both countries. The Rajapaksa government used it to signal tacit US backing for the renewed military campaign against the LTTE, and the US gained an additional logistical hub for its forces transiting through the South Asian region.

The essence of the ACSA agreement was a legal framework for the US and Sri Lankan militaries to seek logistical support, supplies and services from each other, in exchange for payment either in cash, by replacement of the supplies provided, or through an ‘equal value exchange’ for other support, services or supplies.

For the US, this meant they could request the use of Sri Lankan facilities to service and resupply their forces moving through the region. For Sri Lanka, the main beneficiary was the navy, which worked closely with the US navy in finding and hunting down the LTTE arms smuggling fleet throughout the Indian ocean.

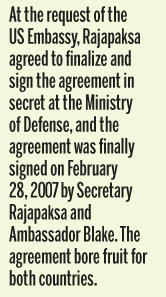

Defence cooperation between Sri Lanka and the US increased since 2015, with the Sri Lanka Navy in particular packing its annual schedules with ship visits, joint exercises, training for the creation of the first SLN Marine Battalion and capacity and capability enhancement.

The agreement itself was just seven pages long, covering the basic terms for how each government could make a request to the other, how requests could be accepted and fulfilled, and how payment could be made. Each government had the ability to refuse any request. The agreement did not allow for either the US or Sri Lanka to force the other country to provide any service or supplies against their will.

Accompanying the 2007 seven-page agreement were thirteen annexes, two with instructions and eleven with contact information for points of contact (POCs). One was an order form from which one government could make a request or place an order with the other government. Another annex listed the minimum information required with any request or order. There was an annex that included POCs for the Sri Lankan Ministry of Defence, which was to handle all inward orders from the US, and all outward orders from the Sri Lankan military.

The US did not nominate a single POC for its Defence Department. Instead they nominated different points of contact for each of its ten military commands spread across the world, who were authorised to accept orders from Sri Lankan forces or to place orders with the Sri Lankan Defence Ministry. The contact details for these units formed the remaining ten annexes of the 2007 Rajapaksa-Blake ACSA agreement.

The US did not nominate a single POC for its Defence Department. Instead they nominated different points of contact for each of its ten military commands spread across the world, who were authorised to accept orders from Sri Lankan forces or to place orders with the Sri Lankan Defence Ministry. The contact details for these units formed the remaining ten annexes of the 2007 Rajapaksa-Blake ACSA agreement.

Effectively, the agreement served as a framework for the militaries of the two countries to buy and lease goods and services from each other. It lacked the language of a treaty, alliance or any other form of agreement that would have allowed the US to put up a military base in Sri Lanka or occupy any Sri Lankan military installations. Nor did it provide for a mechanism by which US troops could enter or leave Sri Lanka, or for Sri Lanka to have to get involved in any US military operations.

However, when the agreement expired after running its ten year course in February 2017, the Sirisena-Wickremesinghe government did not automatically renew it, but instead engaged in brief negotiations to bring the accord up-to-date. Many of the changes introduced into the new draft were cosmetic, but some impacted the operation of the agreement.

For example, the new draft stated that our Coast Guard would be considered part of the Sri Lankan military. Also, new language stated that neither country “shall place an order” “unless it has funds available to pay for such support,” making provision for support to be cut off if funding has not been authorized in advance.

In several parts of the 2007 agreement where restrictions were earlier based on US laws or munitions lists, the 2017 version replaced this language to include Sri Lankan laws and regulations by replacing references to US laws with the phrase “under the national laws and regulations of the Parties.”

Provision was also added to allow more types of spare parts to be traded, as well as chaff and chaff dispensers for aircraft. Language was also added to make clear that the agreement specifically applied to port calls by vessels of one country in the naval bases of another.

Definitions were added for “point of contact” and “classified information.” Where no specific method was stipulated in 2007 for updating the contact information of a party, a mechanism was introduced for updates to be made to names, phone numbers or email addresses by exchanging diplomatic notes. A new requirement was added that both parties have to maintain records of all transactions.

At 90-day period required for one party to propose amendments to the agreement and enter negotiations was removed, allowing either party to propose amendments and request prompt negotiations on any point of need. Unlike the earlier agreement which had a ten-year lifespan, this agreement would remain valid until cancelled by either party with six months’ notice.

At 90-day period required for one party to propose amendments to the agreement and enter negotiations was removed, allowing either party to propose amendments and request prompt negotiations on any point of need. Unlike the earlier agreement which had a ten-year lifespan, this agreement would remain valid until cancelled by either party with six months’ notice.

The number of annexes was reduced from 13 to 12 by condensing the order form and instructions into a single annex. The length of the annexes that listed contact information for US commands increased significantly because the US authorized more of their military commands to seek supplies and services through Sri Lanka.

After several months of negotiations, the final draft was presented by the Defence Ministry to the Cabinet of Ministers for Cabinet Approval. Absent any controversial changes in the new agreement and given the value and success of the earlier agreement entered into during the Rajapaksa-era, Cabinet approval was granted.The new agreement was signed by Defence Secretary Kapila Waidyaratne and US Ambassador to Colombo Atul Keshap on August 4, 2017.

The Sunday Observer performed a word-to-word comparison between the 2007 and 2017 agreements, spurred by grave allegations carried in widely known, reputed and credible newspapers and TV newscasts that 2017 ACSA gave US forces new rights and privileges in Sri Lanka, and that Sinhala and Tamil translations ofseveral critical annexes containing controversial details were withheld from Cabinet, giving rise to a violation of Sri Lankan sovereignty and other threats to national security.

For a legal blackline comparison of the 2007 and 2017 agreements conducted by the Sunday Observer see PDF below.

Our analysis revealed that each and every one of these claims was false, raising questions about the motives behind such a coordinated attack against one of Sri Lanka’s strongest allies at the same time that some political elements are spreading inflammatory rumours that another close Sri Lankan ally, India, had a hand in orchestrating the deadly Easter terrorist attacks.

Security experts who spoke to the Sunday Observer, some of them retired military officials who had been involved in the 2017 ACSA negotiations, explained that the agreement in no way allows the US or Sri Lanka to access each others’ territories freely and without prior authorisation.

Even New Delhi signed an ACSA equivalent with the US in 2016 – an agreement known as LEMOA – for mutual logistical and servicing support between the two nations. In fact, the reality was that over 50% of Washington’s bilateral relationship with any country in the Indo-Pacific region relates to defence cooperation in the face of what the Western superpower sees as a looming threat to its security and economic interests from a rising China, a retired security official explained.

One thing to be wary about, as Sri Lanka enters into these defence cooperation agreeements with the US, is how other powerful countries in the region view this engagement, said Dr Harinda Vidanage, Director of the Bandaranaike Centre for International Studies. Playing down the hysteria about ACSA and SOFA, Dr Vidanage said there were some 70 odd ACSAs signed between the US and other countries and over 100 US SOFAs worldwide.

Dr Vidanage said Sri Lanka needed to be cautious about how our interests were balanced with China and other powerful nations in the region. “We may be prone to agree with other countries for similar agreements. Because you cannot get into such agreements with the USA and then refuse to agree into similar agreements with other countries,” he explained.

The key was in the skill and strength of the GoSL negotiators hammering out the draft provisions of these agreements with US Government representatives, to ensure Sri Lanka’s interests were looked after, he explained.

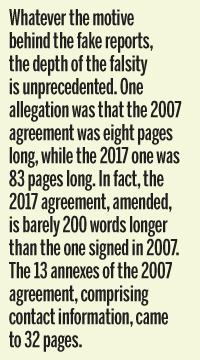

Whatever the motive behind the fake reports, the depth of the falsity is unprecedented. One allegation was that the 2007 agreement was eight pages long, while the 2017 one was 83 pages long. In fact, the 2017 agreement, amended, is barely 200 words longer than the one signed in 2007. The 13 annexes of the 2007 agreement, comprising contact information, came to 32 pages.

Whatever the motive behind the fake reports, the depth of the falsity is unprecedented. One allegation was that the 2007 agreement was eight pages long, while the 2017 one was 83 pages long. In fact, the 2017 agreement, amended, is barely 200 words longer than the one signed in 2007. The 13 annexes of the 2007 agreement, comprising contact information, came to 32 pages.

While the sheer number of pages in the annexes to the 2017 agreement went up from 32 to 67, every single one of these additional pages just consists of nothing other than the name of a US military unit, its telephone numbers and postal addresses, for the purpose of communicating about requests with the Sri Lankan Defence Ministry. The claim that these elements could have a “footprint” or “boots on the ground” in Sri Lanka as a result of this agreement is a fairytale plucked out of thin air.

Another claim was that the 2017 agreement was signed at the behest of the United States. However, pressure was mounting on the Sri Lankan government from the United States to extend the 2007 ACSA long before it expired in February 2017.

Unlike when Gotabaya Rajapaksa took over negotiations and told the US in January 2007 that he was ready to sign their agreement “at any time convenient to the United States” no questions, the current government adopted a considered approach and evaluated and updated nearly every paragraph of the agreement. These negotiations took almost six months, and sign off was received from all three armed forces commanders before the final agreement was signed in August 2017.

The roots of the media hysteria about ACSA appear to be in the shock experienced at some powerful diplomatic missions in Sri Lanka whose home nations were put off by the immediate and high-impact assistance rendered to our country by law enforcement and intelligence agencies of the United States, India, United Kingdom, Australia and Canada, in the aftermath of the Easter attacks.

Law enforcement officers from the United Kingdom’s Scotland Yard, the US Federal Bureau of Investigation, Royal Canadian Mounted Police, Indian Central Bureau of Investigation and Australian Federal Police, flocked to Sri Lanka to assist the Defence Ministry and Criminal Investigation Department (CID) to hunt down Zahran Hashim’s terrorist cell and their co-conspirators.

In a similar vein, intelligence officers from these countries were also invited into Sri Lanka to assist the State Intelligence Service (SIS), Directorate of Military Intelligence (DMI), Police Special Branch and other domestic espionage arms with their efforts to better understand and combat the threat posed to Sri Lanka by Islamist militants.

To some countries who consider these Sri Lankan allies as their adversaries, the prospect of closer cooperation and stronger ties between Sri Lanka and this bloc of nations was irksome to say the least. The ACSA agreement, now almost two years old, made a prime target for media personalities and even military officers whose business and political allegiances have swung towards more communist oriented nations in recent years.

Even some military officers who had been full-throated supporters of the original and 2017 ACSA agreements had sudden changes of heart after travelling to the wrong country. For example, as navy commander, Admiral Ravi Wijegunaratne was a strong proponent of ACSA, deeply involved in the renegotiation that took place in 2017. However, now as Chief of Defense Staff, after a June 2019 trip to Moscow, the admiral came back as a sudden opponent of military agreements with the United States. “If the security forces are involved in the discussion, they would not agree to such requests,” he said.

Ironically, opposition to the US agreements emerging largely from within Sinhala nationalist quarters of the political spectrum, backed by professional bodies similarly is echoed from within the Tamil Diaspora. In September 2018, during a meeting with the US Congressional Caucus on minority and religious affairs, several Tamil diaspora groups strongly urged the US Department of State and the Department of Defence to cease military cooperation with the Sri Lankan Government until commitments made at the UN Human Rights Council in Geneva to address allegations of war crimes were met. The Tamil lobby groups complained that the US and the UK had engaged in military cooperation with Sri Lankan troops 44 times in the past four years.

NOTE:

The Sunday Observer performed a word-to-word comparison between the 2007 and 2017 agreements, spurred by grave allegations carried in widely known, reputed and credible newspapers and TV newscasts that that 2017 ACSA gave US forces new rights and privileges in Sri Lanka, and that Sinhala and Tamil translations of several critical annexes containing controversial details were withheld from Cabinet, giving rise to a violation of Sri Lankan sovereignty and other threats to national security.

Due to space constraints, the legal blackline comparison of the 2007 and 2017 agreements conducted by Sunday Observer was not published in the print edition of the newspaper. Please see PDF below.