This article is an unpublished memo written in December 2016 now formatted for newspaper publication. It has not been updated in the light of any developments since then.

Following the defeat of the JVP and LTTE insurgencies, national security-policy making in Sri Lanka remains reactive and operationally focused. The apex national security body – the National Security Council – is disorganised, tactical and reactive. Thus, the risk of political violence resuming remains substantial. This article argues that reforming the NSC, placing it on a formal statutory footing and appointing a National Security Advisor could go a long way in improving Sri Lanka’s post-war national security through improved strategy, coordination and implementation.

But first, a bit of background. Since Independence, Sri Lanka’s security policy-making has, more often than not, been characterised by:

1.Poor inter-agency coordination among security agencies – including the three services, police and intelligence agencies – and between the security sector and civilian agencies. Inter-agency rivalry has prevented informed, integrated national security policy-making, often making policy the result of bargains between different agency interests.

2.Adhoc policy formulation, which has been reactive and tactical. The absence of formal institutional processes for strategy development, multi-stakeholder input into the policy-formation process and absence of long-term strategy to address root causes of violence have left Sri Lanka’s political and military strategies at cross-purposes.

3.Absence of civilian expertise in the policy-making process. Insights from political science, economics, international relations and technology in the policy-making process are limited. Instead, policy-making and strategy are almost the exclusive preserve of military officers operationally-oriented and equipped with very limited grand strategy skills. Civilian involvement in security policy is constrained to an administrative civil service sans security expertise. As a result, Sri Lanka’s security policy is largely reactive or tactical and does not focus on prevention or addressing long-term threats in a strategic, coordinated fashion.

3.Absence of civilian expertise in the policy-making process. Insights from political science, economics, international relations and technology in the policy-making process are limited. Instead, policy-making and strategy are almost the exclusive preserve of military officers operationally-oriented and equipped with very limited grand strategy skills. Civilian involvement in security policy is constrained to an administrative civil service sans security expertise. As a result, Sri Lanka’s security policy is largely reactive or tactical and does not focus on prevention or addressing long-term threats in a strategic, coordinated fashion.

4.Inability to integrate internal and external security.

Consider the failure to link Indian intervention in Sri Lankan affairs – for example, the arming of the LTTE and intervention of the Indian Peacekeeping Force – to global and regional geo-political balances-of-power. The Jayawardene Government should have realised that its cold war era foreign policy choices had serious implications for internal security.

These deficiencies are particularly salient following the end of the war. Sri Lanka’s three main security threats for the foreseeable future- outlined below -require deep coordination, long-term policy-planning, civilian expertise and navigating the nexus of internal and external security. The main security threats are:

A. The resumption of ethnic violence: despite the defeat of the LTTE in 2009, core grievances of the Tamil community remain unaddressed. Tamils - and other minorities - remain second-class citizens and many are economically backward. Although there is little appetite for violence domestically, the history of violence and possible involvement of some extremist diaspora members means there is always some risk of isolated attacks.

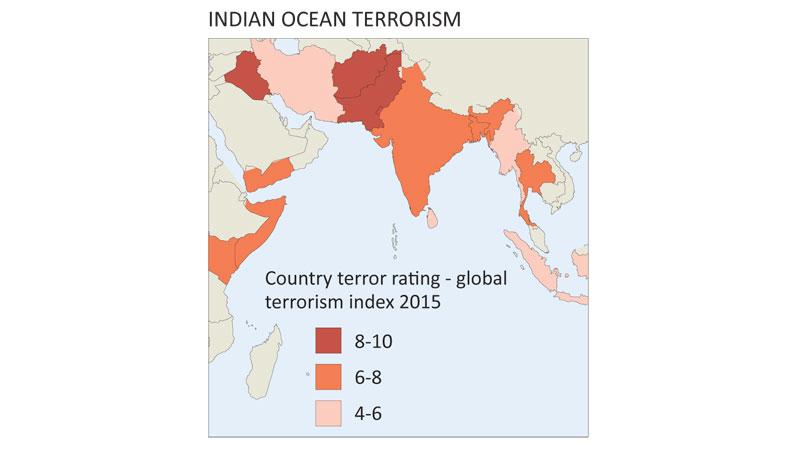

B. Islamic extremism:Sri Lanka is the star to a crescent of emerging Islamic extremism. The Horn of Africa, the Middle East, Indian Sub-Continent and South-East Asia are sites of violent extremist activity and ripe for further radicalisation. This has been exacerbated by Buddhist extremism (and Tamil communalism) and close financial and people-to-people links with centres of Islamic extremism that is radicalising Sri Lanka’s domestic Muslim population.

C. Great Power rivalry: After a hiatus of nearly 200 years, following the end of British, French and Dutch rivalry in the Indian Ocean, the region is once again emerging into a major theatre of great power competition. The US, India, China and their respective allies (e.g. Australia, Pakistan) have competing geo-strategic and geo-economic interests in the Indian Ocean and Sri Lanka’s geographic location means it is becoming a focal point in this competition.

Problem analysis

The failure to overcome the above institutional weakness and adapt to current security priorities stems from a long-term mismatch between rapid expansion in the size, capabilities and function of the security services and institutional development.

The security sector now uses much of the country’s manpower and economy. The threats Sri Lanka faces have also evolved considerably since 1948. But the structure of security policy-making reflects Sri Lanka’s security environment at Independence – a ceremonial army and a treaty-based security guarantee from the UK.

The only major reforms are initiating two intelligence services – the State Intelligence Service (former National Bureau of Intelligence) and Directorate of Military Intelligence - and a joint operations command. Other institutional reforms,such as the introduction of a National Security Council and Chief of Defence Staff, have largely been cosmetic. At the heart of this failure to reform security policy-making institutions is the ineffective National Security Council, the apex national-security decision-making body in Sri Lanka. This executive body often consists of the President, Prime Minister, Defence Minister, Foreign Minister, Chief of Defence Staff, service chiefs and intelligence heads. But the precise membership does not appear to be specified and changes in an ad hoc fashion. Nor does the NSC appear to be formed properly: there is no evidence of an administrative or legal instrument creating the NSC.

However,what is clear is that the current NSC process is leaderless and lacks expertise. It suffers from four main shortcomings. First, it is operational rather than strategic.

Sri Lanka does not have a defence review or national security strategy development process. Lakshman Kadirgamar was appalled that minutes were not kept at NSC meetings and started keeping them himself until the process was rectified. I am reliably informed that, in the past decade, much of the time minute keeping has been haphazard.

Second, the NSC is institutionally crippled.The Council does not have institutional leadership in the form of an NSA or a dedicated secretariat. Thus, no one person is responsible for managing the process and even the most basic of bureaucratic best practices are not followed.

Third, the Security Council is dominated by the military.None of the civilians on the Council have ‘domain expertise’ on national security. Nor do they have access to civilian advisors and counsel. The military dominates decisions without significant debate or scrutiny.

Fourth, the NSC is unable to integrate foreign policy and defence, the Council is almost solely concerned with the internal operationalisation of internal security decisions, with little understanding or exploration of how foreign policy and defence interact to affect national security.

Recommendation

To overcome these shortcomings many countries – especially, those modelled on Anglo-Saxon military traditions like Sri Lanka- have effectively used a formal National Security Council process and National Security Advisor.

Therefore, the President should appoint and empower a National Security Advisor as the principal civilian advisor to the government on national security. The NSA should be responsible for running the ‘NSC Process’ as an ‘honest broker.’

Considering the overwhelming role the military currently plays in national security policy-making and the dearth of civilian security expertise in the civil service, appointing an external NSA may be prudent.

A recent study by J.P. Burke found the United States’ NSA had responsibilities, which could constitute the Sri Lankan NSA’s basic Terms of Reference. (See Table I)

Perhaps the pre-eminent weakness of Sri Lanka’s national security system is the absence of a dedicated NSC Secretariat. Creating an NSC Secretariat under the leadership of the NSA and staffed with civilian experts would enable coordination of policy-making and help integrate and check political, bureaucratic and operational actors.

Critical for the NSC’s success is to develop a formal inter-agency NSC process for policy-formulation headed by the NSC and led by the National Security Advisor. This process should also be used in the development of quadrennial defence reviews and national security strategies.

Considering the grave problems of the status quo, the success of the NSC/NSA model in major defence partners and the absence of tested alternatives, evaluation of alternatives may be beyond the scope of this memo. This is buttressed by Table II, summarising the effectiveness of NSC reforms in addressing the shortcomings identified earlier in the memo.

Implementation

The chief obstacle and risk of introducing these reforms is the delicate state of civil-military relations following the end of the war and the transition away from soft-authoritarianism. The expansion of civilian expertise, management and control over national security policy-making is likely to be resisted.

However, (i) widespread acceptance of the NSA and NSC model across the Commonwealth, (ii) general acknowledgement that Sri Lanka’s security policy-making needs to be more strategic and (iii) absence of NSC reforms having an effect on core personal interest of military officers (e.g. rank, promotions) means that resistance is likely to be confined to bureaucratic impediments. And as demonstrated in Chile, Taiwan and India, with tenacity at the political level, these obstacles can be overcome.

Therefore, the capabilities, relationships and personality of the first NSA will be vital in ensuring the re-organisation’s success. He or she must (i) have deep security and/or foreign policy expertise, (ii) command the President/Government’s confidence, (iii) know how to navigate government policy-making and (iv) have credibility in the security sector.

To operationalise the reform process and secure bureaucratic and military buy-in, the President could consider appointing a three-member commission to study these reforms consisting of a senior civilian expert as chair, combined with a senior military officer and civil servant.

Following the Commission’s report, a Cabinet paper can be presented and the reforms operationalised. It may also be wise to require that the NSA is approved by the Constitutional Council and is required to testify before the Sectoral Oversight Committee on National Security on a quarterly basis.