Could Sri Lanka prevent elephant deaths by train collision? A positive step has been taken by the Ministry of Transport with the recent appointment of a Committee to Prevent Elephant Deaths by Train Collision (CPEDTC). While the Committee plans to establish long term measures within a period of two years, collisions could be reduced 80 % by short-term measures said Dilantha Fernando, General Manager Railways (GMR).

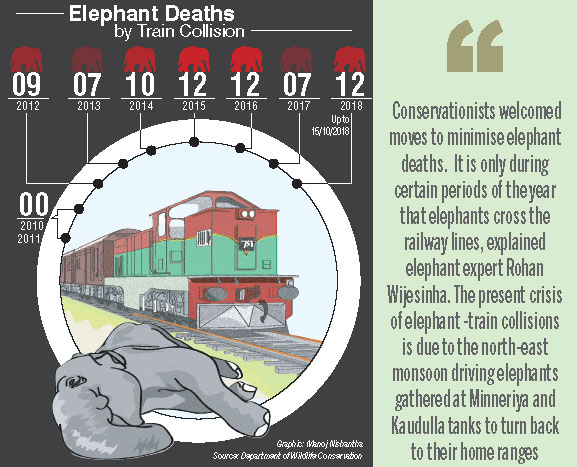

It was a month ago, on September 18, that four elephants died after colliding with an oil train at Puwakpitiya, between Gal Oya and Palugaswewa, on the Colombo-Batticaloa railway line. Early this month, another three, a mother elephant and two calves died on the same railway line, at Namalgama between Welikanda and Poonani. The same week, another elephant was reported hit, critically wounded and died later. The year so far, recorded 12 elephant deaths by train collision according to the Department of Wildlife Conservation (DWC). Last year it had been seven.

It was a month ago, on September 18, that four elephants died after colliding with an oil train at Puwakpitiya, between Gal Oya and Palugaswewa, on the Colombo-Batticaloa railway line. Early this month, another three, a mother elephant and two calves died on the same railway line, at Namalgama between Welikanda and Poonani. The same week, another elephant was reported hit, critically wounded and died later. The year so far, recorded 12 elephant deaths by train collision according to the Department of Wildlife Conservation (DWC). Last year it had been seven.

Conservationists welcomed moves to minimise elephant deaths It is only during certain periods of the year that elephants cross the railway lines, explained elephant expert Rohan Wijesinha. The present crisis of elephant -train collisions is due to the north-east monsoon driving elephants gathered at Minneriya and Kaudulla tanks turn back to their home ranges.

Elephants use established corridors of which both the DWC and the Sri Lanka Railways (SLR) are aware of, said Wijesinha. The Wildlife and Nature Protection Society (WNPS) had submitted their research data and records to both departments. The ultimate solution for the problem is to establish overpasses or underpasses, either for the animals or for the trains as in some other countries. The forested and hilly terrain restricts the advantages that could be gained by heat detecting cameras and other sensors, he explains.

Awareness and caution on the part of the locomotive drivers is of prime importance as the lives of these gentle pachyderms lie in their hands. “They are not huge distances. It is a few particular areas. There is no other technology at hand at the moment but to drive at a speed at which the train could be stopped fairly quickly.”

However, further study needs to be conducted and scientific data gathered before to establishing elephant passes, said Dr. Sumith Pilapitiya former Director General of WDC expressing his views at the monthly lecture series of the WNPS on Thursday. Though SLR could reduce train speeds at short stretches, “at 35 kmph it takes over 100 m to stop. In the night you can’t see 100 m in front,” he said pointing out what needs to be determined is the reason why the elephants were on the track.

“Elephants sense vibration. So, why are they on the track when a train comes? Why don’t they get off because they sense it coming long before the train or the locomotive driver sees them?” he questioned. Though he had not studied the particular situation, his observations on elephant crossings had revealed that while male elephants wait till the vehicles move away, when it comes to herds, once they pass the threshold of an adjacent three to four metres, they won’t stop till the whole herd crosses over. “If a baby stops the whole group stops in the middle. I don’t know whether it was something like that, or if the sides were too steep for the babies to step off so whether they were walking on the track to find another suitable place. We need to study this issue much more to really solve the problem.” He proposed radio-collaring the herds to investigate their movements and to determine common crossing points to bring a permanent solution to elephant-train collisions. However, “without understanding their behaviour just because we think an underpass would be suitable for a particular location don’t expect the elephants to use it,” he commented.

According to DWC Director General, Chandana Sooriyabandara the department had done their best in making locomotive drivers aware of the dangers by erecting signs to warn them from a distance. Further, DWC has been providing expertise to the Sri Lanka Railways (SLR) and Transport Ministry to mitigate deaths by train accidents.

For GMR, M. Dilantha Fernando, the issue poses a problem to SLR. “The trains get damaged. Repairs are costly. Further, we have made the train schedule taking reduced speed limits into concern. We cannot reduce it anymore,” said Fernando. The current system while allowing reduced speed limits at elephant crossings/passes allows normal speed in the areas where there are electric fences. Where the three elephants died earlier this month, was an area demarcated with electric fencing, he explained.

Though the SLR had provided solutions for the problem by fixing thermal cameras, it was not viable as the cameras tended to show heated rocks on either side of the railway track as elephants. Further, it was difficult for locomotive drivers to keep a constant eye on cameras while driving.

A pilot project using electronic circuits implemented at Settikulam on the Mannar railway line though yielding good results had to be abandoned because the electronic-chip was stolen, said Fernando. SLR plans to establish a system of sensors to detect the presence of elephants on the railway track or in the vicinity, within eight months from the CPEDTC report and costing. The system would also include security measures to protect equipment from burglars.

The CPEDTC, conducted their data gathering mission from October 10 to 15, inspecting the railway lines from Mahawa Junction up to Batticaloa, Trincomalee, Elephant Pass on the Jaffna railroad and Yodhawewa in Mannar, the range where elephants roam. The report is due to be handed over to the Minister of Transport & Civil Aviation Nimal Siripala de Silva, in the coming week.

CPEDTC would first identify the critical, sensitive and non-essential locations and provide solutions accordingly, said Committee Member Irosh Perera.

3D creation by Indula Jayasekara |

They would also look at building underpasses and bottle-necking as long term solutions in addition to establishing an electronic sensor system on a short term basis. According to Perera, the terrain has a lot of potential to develop underpasses for the animals at established elephant corridors, while railway tracks would use flyover bridges. They plan to use bio fencing as barriers, guiding elephants to established corridors and passes preventing deaths such as those which happened earlier this month. Environmental experts would be consulted for bio-fencing.

Electronic fencing, employing infrasonic and ultrasonic wavelengths repulsive to elephants and visual lightening effects would be used to keep them away from railway tracks till long term solutions are established, he explained. A specially built electronic system would also be installed to warn locomotive drivers two kilometres before established elephant corridors and passes. Identifying elephants on the track, the system would warn locomotive drivers early as one kilometre away and even a train travelling over the speed of 70 km could stop within 800 metres, said Perera.

If elephants are within a range of 30 m of the railway track, the system would continue the warning till the train slows down to an extremely cautious level. Precaution is taken against system failure, where alternative methods would regularly warn the driver at elephant corridors and passes.

However, the electronic fencing and sensor system would not be able to stop elephant-train collisions 100%, said the GMR, Dilantha Fernando. “We ensure covering 80% of the terrain, reducing elephant collisions. Sometimes, elephants may cross the tracks at places where there are no sensors.”

As immediate measures, the SLR had limited night transport for a short period along railroads where elephant-train collision tends to happen. Furthermore, collaborative efforts are taken with DWC officers monitoring the identified elephant corridors and passes, and accompanying night trains at these areas patrolling parallel roads ahead of the trains.