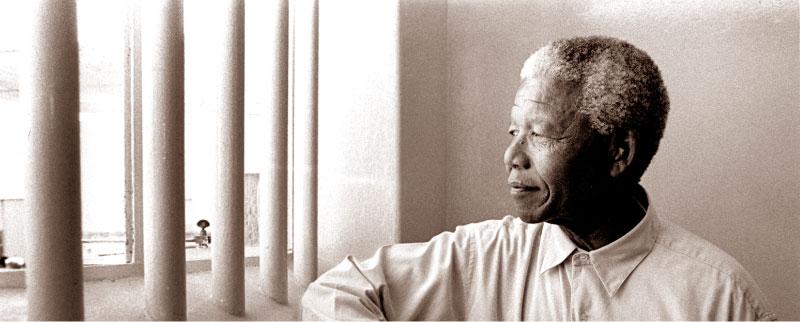

Renowned world over for his commitment to peace, negotiation and reconciliation Nelson Rolihlahla Mandela (as a sign of respect many South Africans referred to him as Madiba - his Xhosa clan name) was South Africa’s first democratically elected President. Mandela was an anti-apartheid revolutionary and political leader, as well as a philanthropist. Born into the Xhosa royal family on July 18, 1918 he died on December 5, 2013

“I am prepared to die” Nelson Mandela

In June 1964, Nelson Mandela was convicted of sabotage for his role as an ANC (African National Congress) activist against the former apartheid regime of South Africa, in which only white people were allowed to vote. Mandela had been accused of inciting strikes by workers and leaving the country without permission of the government.

Before he was sentenced, he made a famous “speech from the dock,” which ends with the words - “I am prepared to die.” Following is an excerpt of the four-hour speech, that probably led the judges in the trial to spare Mandela’s life, thereby altering the course of South Africa’s destiny:

Our fight is against real, and not imaginary, hardships or, to use the language of the State Prosecutor, `so-called hardships`. Basically, we fight against two features which are the hallmarks of African life in South Africa and which are entrenched by legislation which we seek to have repealed. These features are poverty and lack of human dignity, and we do not need communists or so-called `agitators` to teach us about these things.

South Africa is the richest country in Africa, and could be one of the richest countries in the world. But, it is a land of extremes and remarkable contrasts. The whites enjoy what may well be the highest standard of living in the world, while Africans live in poverty and misery.

Poverty goes hand in hand with malnutrition and disease. The incidence of malnutrition and deficiency diseases is very high among Africans. Tuberculosis, pellagra, kwashiorkor, gastro-enteritis, and scurvy bring death and destruction of health. The incidence of infant mortality is one of the highest in the world.

The complaint of Africans, however, is not only that they are poor and the whites are rich, but that the laws which are made by the whites are designed to preserve this situation. There are two ways to break out of poverty. The first is by formal education, and the second is by the worker acquiring a greater skill at his work and thus higher wages. As far as Africans are concerned, both these avenues of advancement are deliberately curtailed by legislation.

The present Government has always sought to hamper Africans in their search for education. One of their early acts, after coming into power, was to stop subsidies for African school feeding. Many African children who attended schools depended on this supplement to their diet. This was a cruel act.

The quality of education is also different. According to the Bantu Educational Journal, only 5,660 African children in the whole of South Africa passed their Junior Certificate in 1962, and in that year only 362 passed matric. This is presumably consistent with the policy of Bantu education about which the present Prime Minister said, during the debate on the Bantu Education Bill in 1953:

“When I have control of Native education I will reform it so that Natives will be taught from childhood to realize that equality with Europeans is not for them . . . People who believe in equality are not desirable teachers for Natives. When my Department controls Native education it will know for what class of higher education a Native is fitted, and whether he will have a chance in life to use his knowledge.”

The other main obstacle to the economic advancement of the African is the industrial colour-bar under which all the better jobs of industry are reserved for Whites. Moreover, Africans who do obtain employment in the unskilled and semi-skilled occupations which are open to them are not allowed to form trade unions which have recognition under the Industrial Conciliation Act. This means that strikes of African workers are illegal, and that they are denied the right of collective bargaining which is permitted to the better-paid White workers.

The lack of human dignity experienced by Africans is the direct result of the policy of white supremacy. White supremacy implies black inferiority. Legislation designed to preserve white supremacy entrenches this notion. Menial tasks in South Africa are invariably performed by Africans. When anything has to be carried or cleaned, the white man will look around for an African to do it for him, whether the African is employed by him or not. Because of this sort of attitude, whites tend to regard Africans as a separate breed. They do not look upon them as people with families of their own; they do not realize that they have emotions - that they fall in love like white people do; that they want to be with their wives and children like white people want to be with theirs; that they want to earn enough money to support their families properly, to feed and clothe them and send them to school. And what `house-boy` or `garden-boy` or labourer can ever hope to do this?

Pass laws, which to the Africans are among the most hated bits of legislation in South Africa, render any African liable to police surveillance at any time. I doubt whether there is a single African male in South Africa who has not at some stage had a brush with the police over his pass. Hundreds and thousands of Africans are thrown into jail each year under pass laws. Even worse, is the fact that pass laws keep husband and wife apart and lead to the breakdown of family life.

Africans want to be paid a living wage. Africans want to perform work which they are capable of doing, and not work which the Government declares them to be capable of. Africans want to be allowed to live where they obtain work, and not be endorsed out of an area because they were not born there. Africans want to be allowed to own land in places where they work, and not to be obliged to live in rented houses which they can never call their own. Africans want to be part of the general population, and not confined to living in their own ghettoes. African men want to have their wives and children to live with them where they work, and not be forced into an unnatural existence in men`s hostels. African women want to be with their menfolk and not be left permanently widowed in the Reserves. Africans want to be allowed out after eleven o`clock at night and not to be confined to their rooms like little children. Africans want to be allowed to travel in their own country and to seek work where they want to and not where the Labour Bureau tells them to. Africans want a just share in the whole of South Africa; they want security and a stake in society.

Above all, we want equal political rights, because without them our disabilities will be permanent. I know this sounds revolutionary to the whites in this country, because the majority of voters will be Africans. This makes the white man fear democracy.

But this fear cannot be allowed to stand in the way of the only solution which will guarantee racial harmony and freedom for all. It is not true that the enfranchisement of all will result in racial domination. Political division, based on colour, is entirely artificial and, when it disappears, so will the domination of one colour group by another. The ANC has spent half a century fighting against racialism. When it triumphs it will not change that policy.

This then is what the ANC is fighting. Their struggle is a truly national one. It is a struggle of the African people, inspired by their own suffering and their own experience. It is a struggle for the right to live.

During my lifetime I have dedicated myself to this struggle of the African people. I have fought against white domination, and I have fought against black domination. I have cherished the ideal of a democratic and free society in which all persons live together in harmony and with equal opportunities. It is an ideal which I hope to live for and to achieve. But if needs be, it is an ideal for which I am prepared to die.

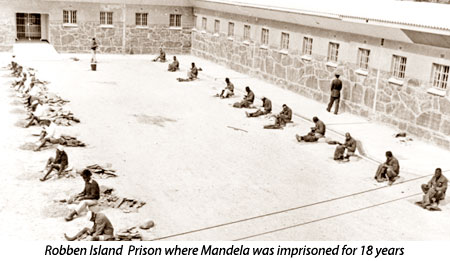

Madiba’s light shone so brightly, even from that narrow Robben Island cell, that in the late seventies he could inspire a young college student on the other side of the world to reexamine his own priorities, could make me consider the small role I might play in bending the arc of the world towards justice. And when, later, as a law student, I witnessed Madiba emerge from prison, just a few months, you’ll recall, after the fall of the Berlin Wall, I felt the same wave of hope that washed through hearts all around the world.

Madiba’s light shone so brightly, even from that narrow Robben Island cell, that in the late seventies he could inspire a young college student on the other side of the world to reexamine his own priorities, could make me consider the small role I might play in bending the arc of the world towards justice. And when, later, as a law student, I witnessed Madiba emerge from prison, just a few months, you’ll recall, after the fall of the Berlin Wall, I felt the same wave of hope that washed through hearts all around the world.

Do you remember that feeling? It seemed as if the forces of progress were on the march, that they were inexorable. Each step he took, you felt this is the moment when the old structures of violence and repression and ancient hatreds that had so long stunted people’s lives and confined the human spirit—that all that was crumbling before our eyes. Then, as Madiba guided this nation through negotiation painstakingly, reconciliation, its first free and fair elections, as we all witnessed the grace and the generosity with which he embraced former enemies, the wisdom for him to step away from power once he felt his job was complete, we understood that—we understood it was not just the subjugated, the oppressed who were being freed from the shackles of the past. The subjugator was being offered a gift, being given a chance to see in a new way, being given a chance to participate in the work of building a better world.

Trials that changed the world:

Nelson Mandela is spared from a death sentence

BY RICHARD J. GOLDSTONE

Nelson Mandela rose to prominence in the 1950s as a leader of the African National Congress, a key opposition group to the apartheid policy of the government in South Africa. In 1963, Mandela and several other ANC leaders were charged with planning to commit sabotage and overthrow the government. Convictions could have resulted in the death penalty.

On Feb. 14, 1995, President Nelson Mandela inaugurated the new Constitutional Court of South Africa. His opening words were: “The last time I appeared in court was to hear whether I would be sentenced to death.” He was referring to the trial in 1963-64 in which he and his comrades had been found guilty of sabotage.

The court was to hear arguments the next day on the constitutionality of the death sentence under our new Bill of Rights. Mandela’s words moved the 11 new justices who had just taken their oaths of office to contemplate how radically different South African history would have been if the three judges who had found Mandela and his comrades guilty of sabotage had imposed the death penalty as requested by the prosecutor. At the conclusion of that trial, Mandela addressed the court. He closed with this statement: “This is the struggle of the African people, inspired by their own suffering and experience. It is a struggle for the right to live. I have cherished the ideal of a democratic and free society, in which all persons live together in harmony and with equal opportunity. It is an ideal which I hope to live for and achieve. But, if needs be, my Lord, it is an ideal for which I am prepared to die.”

The court was to hear arguments the next day on the constitutionality of the death sentence under our new Bill of Rights. Mandela’s words moved the 11 new justices who had just taken their oaths of office to contemplate how radically different South African history would have been if the three judges who had found Mandela and his comrades guilty of sabotage had imposed the death penalty as requested by the prosecutor. At the conclusion of that trial, Mandela addressed the court. He closed with this statement: “This is the struggle of the African people, inspired by their own suffering and experience. It is a struggle for the right to live. I have cherished the ideal of a democratic and free society, in which all persons live together in harmony and with equal opportunity. It is an ideal which I hope to live for and achieve. But, if needs be, my Lord, it is an ideal for which I am prepared to die.”

In the 1963 trial, all but one of the defendants were convicted, but Judge Quartus de Wet stopped short of ordering their executions and instead sentenced them to life in prison. There was a collective sigh of relief in the court. The oppressed majority in our country celebrated the sparing of the life of their hero, and they were joined by millions in the international community. In the Constitutional Court on that day in 1995 we were all conscious that our new constitution and the relatively peaceful transition from apartheid to democracy would not have been possible without Mandela’s leadership, vision and personality. That vision has been a beacon for not only South Africans but also freedom-loving people on all continents.

[Richard Goldstone is a former Supreme Court Judge of South Africa and former Chief UN Prosecutor on the International Criminal Tribunals of the former Yugoslavia and Rwanda ]